By Mark Mussari

When he was 19 years old, Mark Rohrig gathered up some of his paintings and took them to a gallery (now defunct) in Taos, NM. Standing in front of the gallery’s window, the young artist stared longingly at works by some of the painters he most admired. His eyes lingered on original canvases by such western stalwarts as artists Frank Howell and Veloy Vigil, renowned for their expressive images of Native Americans. He dreamed of one day joining their ranks.

“I walked in the door and asked the man who ran the gallery if they were accepting any new artists,” recalls Rohrig. Then a figure emerged out of the shadows in the back of the gallery. “The man knelt down, looked at my work and said, ‘This is great.’ And then he told me, ‘You’re going to shoot the moon.’” To the teenager’s surprise, that man was Frank Howell. Rohrig’s idol then asked him what he had on his easel at the moment. “He told me to send him an 8-by-10 glossy of it,” he recounts. The aspiring painter waited weeks for a response, but it was worth it. The gallery accepted him as a new artist.

“That was the beginning of my professional career,” says Rohrig. “I still get emotional thinking about it.” The following year—1976—the gallery held the first solo exhibition of Rohrig’s work. “I showed 23 pieces, and within three hours, the show had sold out,” Rohrig says. “I set a record for the gallery.”

Rohrig’s love for western art began early. He was born and raised in Grand Junction, CO, and he remembers first drawing when he was 4 years old. “By the time I was 5, I recognized it as something that felt good to do,” he says. “Whenever I was drawing, I felt elated.” Surrounded by Colorado’s magnificent scenery, Rohrig did a lot of exploring as a child. Watching western movies was another favorite pastime, and prints by Charles M. Russell hung on the walls of his childhood home. Western imagery was a part of his boyhood, and the impressionable youth began manifesting it in his drawings. “It was like magic to me. It was a form of escape, too, especially if things weren’t going well,” he admits. Although Rohrig also began playing guitar at an early age and considered becoming a musician, he felt that drawing came more naturally.

As early as elementary school, he garnered attention in local art contests. It was in junior high, however, that he encountered someone who had a profound influence on his future, his art teacher Frances West. “I had one of the best art teachers in the state of Colorado,” he recalls fondly. “She taught us to work in every medium.” That was when he moved from crayons and colored pencils to acrylics, which remain his favored medium to this day.

In ninth grade, Rohrig was named his school’s artist of the year. “By tenth grade, I was already selling my paintings,” he says with pride. “My father had taught me the art of selling. I liked the wheeling and dealing.” His father was a lapidary who cut and polished his own rocks; his mother’s side of the family provided the musical genes.

In his early artwork, Rohrig drew and painted myriad subjects, including mountain scenes, hot rods, and trains. “Later in high school I started seeing Native American images by artists in magazines,” he says, “and it just grabbed me.” He was especially drawn to the art of western painter Frank McCarthy and the revered realist Richard Schmid. Although he took a few art classes at Mesa State College, Rohrig considers himself a self-taught artist. He worked some construction jobs after high school but focused on his painting. Today, the 55-year-old Rohrig is among the relatively small number of western painters who have made their living as fine artists for their entire career.

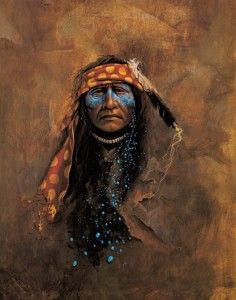

Following the early success of his one-man show in Taos, Rohrig gained representation in galleries in Aspen, Sedona, and Chicago. At first his subject matter included both western landscapes and Native American portraiture. By the mid-1980s, he was striving for what he refers to as an “emotionally closer” effect, and to that end he began concentrating more on portraiture. “I don’t paint specific Indians,” he says. “I’m not trying to copy history; I’m using history for inspiration and as a point of departure.”

Over the years Rohrig has amassed a large personal library of reference materials, and he has become particularly knowledgeable about the Northern Plains Indians, such as the Cheyenne. Rohrig defines the era of his figures as sometime in the late 19th century—from 1870 to about 1910. “Their culture was more intact at that time,” he observes, “even though it was also a time when their world was changing.” For all the research he has done over the years, he maintains that his attraction to the spirituality of Native Americans can be traced to his childhood. “It has always stayed with me,” he adds. “I paint an Indian that’s noble and

enduring.”

In this sense, his portraiture seamlessly melds his lifelong affection for Native cultures with an artistic language in which his figures transcend their specific histories to express something more universal. It’s true that he is careful to create accurate details in the fabrics, beading, and feathers he paints. “If I draw a Plains Indian war shield,” he insists, “I want it to look like it should.” But ultimately, the details aren’t the point; the story of each canvas is a larger one. “My approach is to create what I feel and to express something spiritual,” explains the artist.

His piece NIGHT TRAVELER is a good example. A Native American’s face seems to float amidst a canvas of thick brush strokes. “It’s a very warm palette,” says Rohrig, “with lots of earth tones and brilliant color.” A polka-dotted kerchief, white beads, and a black-and-white feather reveal Rohrig’s well-researched approach, yet other details simply disappear into the background. “A visual metamorphosis is happening,” says the artist. “It’s as if he’s fading yet emerging into a new world.”

In WHISPERS OF THE GRANDFATHERS, a Lakota Indian stands regally, staring straight ahead. “He’s looking off into the distance and pondering what the old ones have shared with him,” says Rohrig. “It’s as if he has experienced the wisdom he learned from the ancients. The mystical is in that painting.” Rohrig explains that, in general, the history he paints is his own personal expression, an attempt to connect to his inner being. “To me, the act of painting is naturally meditative,” he notes. Pressed to define his art, he lands on the phrase “mystical realist.” Then he adds, “I’m a realist—but my world is imaginary.”

Rohrig works solely in acrylics, as he has done since his late teens. “I like brilliant color,” he says. “And I like its ability to dry fast.” After starting with a pencil sketch, he usually adds neutral grays as an under-painting. “I may also use purples or deep browns,” he adds, “and end up with what looks like a black-and-white image.” Then he often applies a wash in burnt umber or sienna, layering colors on top of colors to achieve depth. Rohrig maintains a studio in his home and another across town. He works seven days a week, though he admits he often does not begin painting until late afternoon. “I’m very nocturnal,” he says. “I often paint into the wee hours.”

More than anything, Rohrig hopes that his mystical portraits convey something even greater than the subjects themselves: “I want the emotions and spirit in each piece to transfer from the painting to the viewer.” Apparently they are already doing just that—such luminaries as Cher, Kevin Costner, and Mariah Carey have original Rohrigs in their personal collections. Summing up his career, Rohrig says simply, “I get to do what I always wanted to do. I couldn’t ask for more out of life.”

Dossier

Representation

Altamira Fine Art, Jackson, WY; Wind River Gallery, Aspen, CO; Adagio Galleries, Palm Desert, CA; Indian River Gallery, Las Vegas, NV; www.morton-rohrig.com.

UPCOMING SHOW

Three-person show, Adagio Galleries, November 4-30.

Featured in September 2010