Monte Yellow Bird Sr. conveys modern messages through a traditional tribal art form

By Norman Kolpas

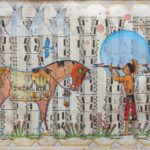

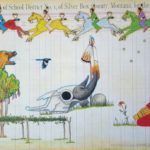

Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Hidatsa Black Mouth Society, colored pencil/ink, 13 x 8.

This story was featured in the March/April 2020 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art March/April 2020 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

A WOMAN KNEELS serenely on the ground in prayer, her eyes gazing resolutely forward. Her red dress symbolizes the blood of all mankind, and the flowers rising around her represent her daughter and sons. High above, four women warriors on horses in ceremonial shades of red, yellow, blue, and green gallop across the night sky, where ancestors shine brightly as stars and Grandmother Moon wards off all fears. A sun-bleached buffalo skull and a perfectly round stone form a sacred altar nearby. Beyond, a tree and arbor provide shelter for solemn ceremonies beneath the bright yellow sun, which represents enlightenment and sends forth strength via a growling grizzly bear whose courageous message is carried onward by a magpie.

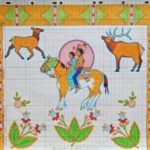

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Bluebird Love Song, colored pencil/ink, 12 x 9.

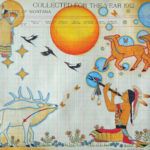

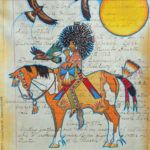

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Bugling the Song of Elk Medicine, colored pencil/ink, 11 x 13.

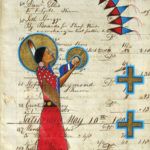

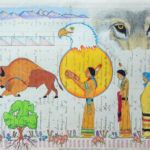

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Grandfather, This Young Life is Holy, colored pencil/ink, 13 x 8.

If the abundance of images in NIGHT WIND WOMAN, AS SHE GROWS DIFFERENT, all drawn on a page from an 1890s Montana school ledger book, sound like the substance of an awe-inspiring dream, it’s because they actually are. This particular vision was related to Monte Yellow Bird Sr.—who creates his artworks under the ceremonial name of Black Pinto Horse—by his friend Dr. Ruth Ann Hall, director of Native American studies at Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College, a tribally controlled community college in New Town, ND. Says Yellow Bird, explaining the overall mes-sage his piece aimed to convey, “She’s a role model for our community and for young women in rising above adversity, an example of strength and endurance and fortitude.” Through his subject, he wanted to “show the beauty in what women really are.”

The artwork stands as a perfect example of how Yellow Bird has been subtly but powerfully transforming ledger art, an American Indian medium more than a century and a half old, into a means of expression perfectly attuned to observing and commenting on the world today. “To put something on paper like this,” he says, “can help bad things lose power over us and help good things gain power in our lives. We can all develop narratives that help us understand some of the difficulties we face.”

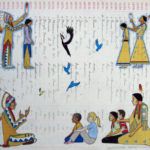

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Childhood Friendship Among All of Creation, colored pencil/ink, 15 x 10.

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Night Wind Woman, as She Grows Different, colored pencil/ink, 12 x 21.

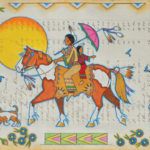

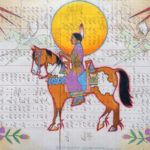

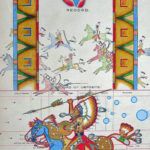

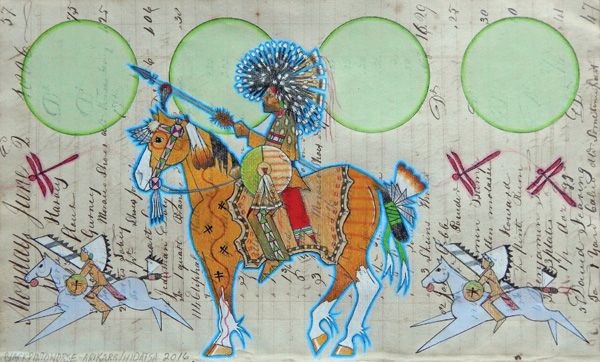

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Rides Among Chiefs, colored pencil/ink, 11 x 13.

ART HAS always played a key role in bringing Yellow Bird a feeling of understanding and strength in a sometimes-precarious world. In 1960, he was born his parents’ seventh son among 11 boys and four girls on western North Dakota’s Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, home to the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara nations. It was a place “rich in heritage but also in deprivations,” as he sums it up.

Early on, his family’s home had no electricity. When power finally came, a black-and-white television arrived soon after to show kindergarten-aged Monte news footage of the Vietnam War. “We didn’t have lots of paper in our home, so on the walls I was making a type of ledger art with army men and tanks and battles. I learned how to draw on the walls,” he adds with a laugh, “but I also learned how to wash walls.”

Not that the boy had much strength to do either. He developed walking pneumonia and Reye’s syndrome, a rare condition that causes the liver and brain to swell. “They expected me to die, and I wound up spending a whole year in the hospital and then more time at home until I made it through.” Helping him endure the hospitalization was the fact that he had two “grandpas”—an honorific given to any older male among extended family—who were also ailing there and took him for walks up and down the hallways, teaching him tribal songs and folk stories. On pads of paper he repurposed from hospital supplies, he’d draw some of the imagery his elders sang and spoke about—“eagle feathers, and pipes, and warriors,” he recalls.

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Three Prayers Sent to Our Chief, colored pencil/ink, 11 x 9.

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Watch the Birdie, colored pencil/ink, 18 x 17.

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., And They Stood Before All of Creation and Became Part of All Good

Once Monte was finally back in school, art remained a constant for him; since “the teachers were really tough on us native kids,” he says, his creative skills became a particular source of strength and pride. “When everybody else was reading books, I was drawing pictures. People were always talking about how much detail there was [in them].” His oldest brother taught art there, and after school Monte would hang out in the art room until it was time for his brother to drive him home. “In fourth grade, I did a drawing of a wolf in the snow and a little cabin. It won a blue ribbon at the state fair and somebody bought it,” he says. Art offered a sense of security: “It opened a veil, where you could walk into your own space and feel successful and cared about and loved.”

Yellow Bird’s teen years brought him more pathways toward inner peace. He learned to train horses, which were a primary means of transportation on the reservation. “I had a knack for communicating with horses, and I’ve trained them for a good majority of my life,” he says. “On my father’s side, we come from horse medicine, a ceremonial and spiritual connection that brings our people and horses together. They have the ability to help people, doctor people. And when it’s time for us to pass over, we believe a horse will carry us over the river to spend eternity with our relatives.”

Starting in his mid-teens, he also gained both spiritual and physical strength through the martial arts—Kajukenbo (a Hawaiian hybrid of karate, judo, kenpo, and boxing), kung fu, and then Taekwondo. By the age of 19, he was running his own training gym in Bismarck, ND, and in 1994 he became the first-ever Native American to win a gold medal at the Taekwondo National Championships. Through that entire phase, he says, “I learned a lot about myself”—not least that such disciplines were ultimately “for healing, not for hurting.”

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., And They Rode Into the Enemy Camp and Recaptured Their Ponies, colored pencil/ink, 19 x 12.

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Elk Medicine Called us Together, colored pencil/ink, 18 x 17.

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Elk Medicine, Calling All Angels, colored pencil/ink, 21 x 16.

Art remained a constant for him throughout those years. At 16, a teacher in North Dakota recommended him for a scholarship at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, the first time he had ever left the reservation. He later went on to major in history education, with a minor in art, at North Dakota State University, and eventually earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Minot State University.

A MILESTONE that perhaps outshined all his other achievements came around 1995, at a time when he was “really trying to get healed and take care of things in my life,” he says. “My grandpa said to me, ‘You were born a healer, and your destiny is to help others.’” With that goal in mind, Yellow Bird underwent a naming ceremony in a lodge of his ancestral Arikara tribe. As he describes it, “Spirits from the north told the old man of a black-and-white pinto horse that ran wild with all the other horses and watched over the herd. They gave me the name Black Pinto Horse and told me that the story explains how my life is going to be, that I’ll watch over others and protect them.” Ever since then, though in his daily life he remains Monte, as an artist he calls himself Black Pinto Horse, “because it attaches me to my spiritual identity.”

More and more since that time, he has focused on ledger-style art, whether he’s working with colored pencils on antique sheets of paper or creating his versions of traditionally styled images with acrylic or oil paint on canvas. He takes great pride in educating children and teens about his people’s history and artistic legacy. His works have won numerous awards and can be found today in the collections of the Great Plains Art Museum at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, and the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, Netherlands.

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., From the Center is Where Life Begins, colored pencil/ink, 9 x 12.

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., I’ll Lead the Charge for Future Generations, colored pencil/ink, 15 x 10.

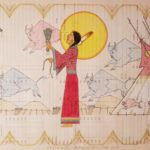

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Red Buffalo Medicine Woman, colored pencil/ink, 11 x 17.

Though they may appear firmly rooted in tradition, Black Pinto Horse’s compositions carry messages very much attuned to issues of the present day. “Doing ledger art,” he explains, “is telling very important teachings and lessons to help people associate with and understand what life is all about, teachings about the preciousness of life, the sacredness of women, and the importance of honoring our Mother Earth.”

By way of example, consider WATCH THE BIRDIE, which subtly plays on the history of indigenous people as they were first photographed in the extensive documentary portraits done by Edward S. Curtis in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Here, however, a contemporary young Indian couple wearing traditional attire poses for an image being taken by a photographer clad in blue jeans. Meanwhile, as the artist relates, this scene is being witnessed by two men dressed in warbonnets, “a younger chief who is asking an older chief questions like, ‘How do I become a better man, a better father, a better leader?’” Two playful puppies near the chiefs represent “two parts of our everyday life, sickness and death, who will always be with us”—and therefore should not be feared. As for the proverbial “birdie” hovering over the photographer’s up-stretched finger, “its yellow color means enlightenment and represents our creator, coming down in a different form to witness this time of transition.”

For a man who has gone through so many transitions himself—from sickly child to martial arts champion, from horse trainer to educator to acclaimed artist—Yellow Bird has contentedly arrived at a stage in life where he seems meant to be. But he modestly demurs at taking full credit for his success. “It’s really important for me to acknowledge my mom, Magdalen, who is 93 years old now, and my grandfathers and grandmothers from generations back,” he says. “They’re my guiding lights in everything that I do. They help me keep my feet on the ground, and help me to help others.”

representation

Ghost Art Gallery, Helena, MT; The Frame Garden, Livingston, MT; The Capital Gallery, Bismarck, ND; Artmain Gallery, Minot, ND; Heard Museum Shop, Phoenix, AZ; Eiteljorg Museum Store, Indianapolis, IN; Autry Museum Store, Los Angeles, CA; IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, Santa Fe, NM; www.blackpintohorsefinearts.com.

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Rejoice, Blessings to the Beasts and Children, colored pencil/ink, 13 x 16.

- Monte Yellow Bird Sr., Strikes Enemy, colored pencil/ink, 13 x 15.

This story was featured in the March/April 2020 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art March/April 2020 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook