Rick Stevens’ paintings combine the earthy and the ethereal

By Bonnie Gangelhoff

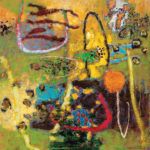

Rick Stevens, Waldeinsamkeit II, oil, 48 x 96.

This story was featured in the February 2020 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art February 2020 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

STEP INSIDE the Santa Fe, NM, studio of painter Rick Stevens and you may hear a few jazz notes from the great Miles Davis floating through the air. In fact, Stevens likes to compare his creative process to that of a jazz musician: He thrives on improvisation. “I make a mark, a shape, or an application and then respond to it, like how a jazz trio might improvise and respond to each other,” he says. “I look for ways to repeat or vary the elements, gestures, patterns, or rhythms in the marks and textures.”

Unlike many artists who follow an established series of steps in their creative processes, Stevens is comfortable breaking out of the formulaic and working intuitively. In a recent work titled DANCING IN PARADOX, the artist began without a sketch or any preconceived plan. He used oils to express his artistic vision, then later decided to collage burlap into one area, add cold wax, and incorporate gold leaf into some carefully selected spots. “Painting is a dance between the known and the unknown,” he says. “We need novelty, surprise, and spontaneity.”

And so Stevens explores light, texture, color, and space while welcoming painterly accidents. This freewheeling approach allows him to slip seamlessly back and forth over the line that separates abstraction and realism. But whether viewers classify a Stevens painting as abstract or representational, the first thing they should know about the artist is that his muse and constant companion is nature. Even the pieces that don’t start with a specific subject in mind usually evolve into suggestions of the landscape.

- Rick Stevens, Aglow, oil, 72 x 48.

- Rick Stevens, Dancing in Paradox, oil, 32 x 32.

- Rick Stevens, Just Being There, oil, 32 x 36.

Nancy Hunter, who represented Stevens at Hunter Kirkland Contemporary in Santa Fe until she sold the gallery recently, says his paintings defy easy categorization. “Rick creates paintings that are more abstract than traditional landscapes, but more representational than typical abstracts,” Hunter says. “Equally skilled in both his mediums, oils and pastels, Rick uses them to produce luminous, richly colored expanses of the natural world. You can look at and study his paintings for years and still find new ways of seeing them. Somehow they manage to be stimulating and calming at the same time.”

WHILE ASPEN trees in northern New Mexico inspire him these days, as a boy Stevens was attuned to the pine trees in his native Michigan. Growing up in the small town of Sparta, he has fond memories of accompanying his father, a landscape painter, on camping and canoeing trips in the northern Michigan woods. “I remember contentedly sitting for hours behind him, watching the paintings develop,” he recalls. As a child he enjoyed drawing the animals and trees he observed in nearby forests. As he grew older, Stevens often painted alongside his father. When it came time for college, it seemed natural for him to study art, and he eventually graduated with a fine-arts degree from Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, MI. By that time, Stevens already had local gallery representation and was earning a small income from his paintings. Then in 1984, a few years after graduation, Stevens took an unusual step in his blossoming art career: He “dropped out” for a year, retreating to a cabin in the Michigan woods to practice the spiritual teachings of Swami Amar Jyoti. Jyoti was from India, but he also had an ashram close to Stevens’ home in Michigan.

- Rick Stevens, Pathway to Wilderness, oil, 48 x 24.

- Rick Stevens, Spring Renewal II, oil, 36 x 96.

- Rick Stevens, The Forest is Calling, oil, 48 x 48.

Stevens was 24 years old at the time. He had no phone, television, or even a small radio in the cabin; his days consisted of painting, yoga, and meditation. “My subject matter was the forest around me and the dappled play of light,” he says. “It was very expansive … until it wasn’t. The experience was formative, but I needed to get back into the world.” The 12-month sojourn cemented his future course as a full-time artist. “It could have led to renunciation, as in becoming a monk, but I was afraid I would have to give up my art,” Stevens says.

Early in his career, the artist supplemented his income with remodeling work and sign painting. Then in 1988, Michigan’s Muskegon Museum of Art invited Stevens to exhibit his work. For a young, emerging artist, it was a significant milestone and honor, Stevens says. More gallery offers came his way, and soon he was making regular trips to Santa Fe for shows at Hunter Kirkland Contemporary on Canyon Road. In 2008 he was invited to stay at a friend’s house in Canoncito, NM. The visit stretched into a month as he painted, hiked, and explored the majestic terrain surrounding him. He eventually returned home to Michigan, packed up his belongings, and relocated to the Land of Enchantment. Today Stevens maintains a studio in Santa Fe but makes his home in Tesuque, a small town nearby nestled in the reddish-brown foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

- Rick Stevens, Auburn Disiduous, pastel, 24 x 24.

- Rick Stevens, Blurred Boundaries, pastel, 20 x 18.

- Rick Stevens, Blurred Boundaries, pastel, 20 x 18.

STEVENS RESISTS placing labels on his work; he prefers to speak more broadly, saying that he considers himself part of a long line of American landscape painters, including the Hudson River School and the Luminists. Some of these 19th-century artists were associated with transcendentalism, a view held by writers and philosophers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Transcendentalists espoused, among other things, a deep appreciation for nature and valued intuition over logic.

Stevens is fond of quoting another famed 19th-century artist, George Inness (1825-1894), who once said, “The purpose of the painter is simply to reproduce in other minds the impression which a scene has made upon him. A work of art does not appeal to the intellect. It does not appeal to the moral sense. Its aim is not to instruct, not to edify, but to awaken an emotion.”

While Stevens says he works under the influence of 19th-century painters like Inness and Albert Bierstadt, he also considers himself part of the next truly “American” art movement that followed, abstract expressionism. This post-World War II movement developed in New York with work that features gestural brush strokes and mark-making that conveys both emotion and a sense of spontaneity.

- Rick Stevens, High Mountain Aspens, oil, 14 x 12.

- Rick Stevens, In the Presence of …, oil, 30 x 45.

- Rick Stevens, Last Light in the Pines, oil, 36 x 72.

If those two traditions seem at odds with each other or opposites, that’s fine with Stevens. His work is all about expressing polarities—incorporating both stillness and movement, calmness and high energy, in a single painting. “I strive to be comfortable holding opposites and giving them space to live and thrive in an image,” Stevens says. “While I want to express movement, I strive for a strong balance in the composition to give it stability as well. Stillness is the central axis of all movement. That may sound like a paradox to some, but it is embodied by a dancer or practitioner of the martial arts.”

These days Stevens is still influenced by Eastern philosophies, but he has traded in his yoga poses for tai chi, a Chinese system of slow, meditative exercises based on Taoist teachings. “It’s great for physical health but also in maintaining harmony and flow in movement,” Stevens says. “Understanding and working with unseen energetic forces, or chi, really helps me sense both movement and implied energetic forces which appear in my paintings. For things that are hard to put into words, it is my experience that if you can embody balance and harmony in yoga and tai chi practices, you can sense it intuitively in paintings.”

- Rick Stevens, Luminous Numinous, oil, 48 x 72.

- Rick Stevens, Moment of Gratitude, oil, 52 x 32.

- Rick Stevens, One Implies the Other, oil, 32 x 36.

Over the years Stevens has developed his own visual style and vocabulary of shapes, patterns, and marks based on Mother Nature’s treasure trove. Like Inness, Stevens has the ability to convey a sense of the earth and the ethereal simultaneously. Finally, while artistic traditions from centuries past play a major role in his art, Stevens is also a painter for the 21st century. In AGLOW, for example, Stevens took inspiration from a reference photograph shot in a favorite spot in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains; he altered the photo using filters and an iPad painting app called Procreate. Lately, he considers these digital compositions as his sketchbook.

The artist’s many forays into nature over the years have strengthened his appreciation for the earth’s fragile ecosystems. Recently Stevens’ work has come full circle, returning to his roots in the recognizable forests and other landscapes that he drew as child. “I revisit my past directions frequently,” he says. “I’m not the type to finish one direction permanently before moving on to something else. I approach things from many angles. My body of work advances more like a spiral than in logical, chronological steps. But all the paintings merge the observable world with the unseen psychic energy beneath the surface that engages us in the never-ending cosmic dance.”

representation

Galerie d’Orsay, Boston, MA; Vail Village Arts, Vail, CO; LaFontsee Galleries, Grand Rapids, MI; Galería Casa Colón, Mérida, Yucatán, Mexico; NoonPowell Fine Art, London, England.

This story was featured in the February 2020 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art February 2020 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook