Sarah Siltala takes time to experience and express the fleeting wonders of life

By Gussie Fauntleroy

This story was featured in the January 2019 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art January 2019 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

There’s a moment, as a dedicated birder is on the verge of sighting a rare or shy bird, when the person almost disappears into the experience of listening and looking, all the senses open and alert. Nothing exists but the feel of the air, the smells and sounds of the woods, and a bright awareness of the tree or bush where the elusive bird may appear. Suddenly, if you’re lucky, there it is—landing and briefly perching, looking at you. In that moment there’s a spark of silent communication between the eyes of the human and bird. As painter and birder Sarah Siltala puts it, “the world just stops.” Then, just as suddenly, the bird flies off.

Siltala has learned that these moments of magical connection can occur only if one has quiet composure and takes time to become immersed in the natural world. Similarly, the New Mexico painter must call upon patience and allow time to achieve her luminous still-life and landscape art. Working in an old masters style that includes producing much of her own oil paint from pigments and linseed oil that she processes herself, she must wait for each of many translucent layers of color to dry completely before applying the next. So it’s appropriate that her imagery captures an instant of breathtaking tranquility: a butterfly or small bird often perched incongruously on a vase or bowl, or the feeling of enormous surging clouds above the vast and wide-open New Mexico terrain.

- Sarah Siltala, Meander, oil, 20 x 24.

- Sarah Siltala, Passing Storm, oil, 24 x 24.

- Sarah Siltala, Lured by Beauty, oil, 18 x 14.

Siltala brings to her work a lifetime habit of deeply observing these and other aspects of the world. It’s an inclination gained by example from parents who were both professional artists, and by growing up in Santa Fe surrounded by visual beauty, cultural and creative expression, and art at every turn. Her father, Kenyon Thomas, was an exceptionally talented ceramic artist who also painted intricate flora and fauna on his vessels and later shifted to landscapes in pastel and oils. Siltala’s mother, Marcia Thomas, was a fiber artist working in ikat hand-dyed yarn when her three daughters were young. Both parents were also musically inclined.

Although as a child she didn’t draw or paint, Siltala was so immersed in the world of art that she took it for granted, as if that’s how everyone lived. Yet she continuously absorbed it, learning by watching her parents go to work in their studios, prepare for shows, socialize and trade with other artists, and generally put a creative touch on everything they did. The family home was a small pink adobe surrounded by trees and her parents’ gardens and filled with original art. “Our house was rich with beautiful things,” she says.

Not far away were galleries and art museums, and in high school Siltala worked at an art and antique gallery in the city’s historic art district of Canyon Road. Her mother had trained as a concert pianist as a young woman, and early on Sarah took piano lessons and spent hours at the piano, teaching herself from her mother’s sheet music. During summers she volunteered with the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival.

- Sarah Siltala, Nuthatch and Pear, oil, 10 x 10.

- Sarah Siltala, Pitcher and Pears, oil, 16 x 20.

- Sarah Siltala, Still Life With Bluebird, oil, 18 x 14.

When it came time for college and a career, Siltala wanted something that felt like her own, rather than following her parents’ footsteps into visual art. She enrolled in the music program at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. But her college career was fraught with hurdles. One year she became seriously ill and was also in a car accident, which led to falling behind in her studies. Increasingly she found herself suffering from performance anxiety. She felt lost, as if she didn’t belong in the music field. When she finally gave herself permission to leave the program and UNM, she was washed over with relief. “I truly believe the universe was guiding me. I was not meant to be a musician,” she says.

Siltala knew that closing that door meant others would open, and soon they did. In her mid-20s, married and with an infant son, she suddenly was overcome with a powerful desire to paint, specifically in oils. It came out of the blue like a lightning bolt. She had not painted before; her parents didn’t paint in oils at the time; and her younger sister, an artist, had chosen watercolor. But there it was, an undeniable urge. When she told her family, they encouraged her. Her sister gave her all the oil painting materials she’d purchased before deciding it wasn’t her preferred

medium—paints, canvases, easel, brushes. “There’s no way I could have afforded all that at the time,” Siltala says. “It was amazing. Many blessings began showing up in my life when I finally discovered my passion for art.”

She found a library book on painting and used it to teach herself. As it happened, the book presented a classical style of “indirect” painting. That meant first perfecting the drawing and composition; then adding in the main values, or darks and lights—which Siltala does in brown and white-—and finally building color through multiple thin washes of paint. “You can really concentrate on each creative element, one step at a time,” she notes. “It’s very logical, and it’s how paintings were completed for hundreds of years, beginning in the Renaissance. I don’t feel like I chose that style and method. I feel like it chose me.”

- Sarah Siltala, Stillness, oil, 10 x 8.

- Sarah Siltala, Be Still, oil, 18 x 18.

- Sarah Siltala, Desert Evening, oil, 8 x 10.

Just as the creative process came naturally to her, Siltala’s transition into a painting career was also surprisingly smooth, fueled by creative excitement and the art-world knowledge she had internalized over the years. By then her parents were living in Ruidoso, NM, where they had opened a gallery. They took on some of her paintings and made a sale within the first month. Then she was asked to join a Santa Fe gallery, where people frequently commented with pleasure on her old-world style.

At the time, Siltala was working primarily with commercial paints, although she also experimented with the old-masters method of making egg tempera paint with dry pigment and egg yolk. One day she ran out of an oil color, so she decided to try mixing pigments with linseed oil to make her own. “It was wonderful. Each pigment has a different quality and personality,” she says. That led to teaching herself to make her own oil medium, using various processes to purify organic flaxseed oil before mixing in pigment. She often adds minerals as stabilizers and to control the paint’s qualities, including its handling and flow. “They’re all natural additives that can be found in samples of Renaissance-era paint,” she says.

- Sarah Siltala, Common Yellowthroat, oil, 10 x 10.

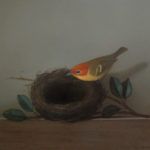

- Sarah Siltala, Little Wren, oil, 8 x 10.

- Sarah Siltala, Magpie and Water Pitcher, oil, 20 x 16.

For Siltala, one of the rewards of her approach is seeing jewel-toned colors appear as she applies layer upon layer. She often uses large “mop” brushes and non-traditional materials to manipulate wet paint, allowing tiny specks of the previous color to show through and visually blend with the other layers. “It’s a joy to me, to watch the colors grow over time,” she says.

In her still-life paintings, this depth and richness of color is combined with simple compositions featuring minimal objects, enhancing the feeling of tranquil beauty. STILLNESS, for example, places a large butterfly with open wings on the lip of a small ceramic jar. Against an intensely black background, the only other element is white drapery over a wooden board. The painting was inspired by 17th-century Dutch artist Adriaen Coorte, one of Siltala’s favorites, who also distilled his imagery to one or two objects. “I’ve always been attracted to quiet compositions,” she says.

Small birds began entering Siltala’s paintings when she lived on an Albuquerque-area property shaded by tall cottonwoods, with a large pond behind the house. From her studio windows she could see countless birds, including songbirds, ducks, herons, owls, and hawks. “It was charming to sit and watch, to slow down and observe,” she says. An avid birder and photographer, she soon accumulated a large collection of bird photos to choose from when planning a new piece.

- Sarah Siltala, Memento, oil, 10 x 10.

- Sarah Siltala, Oriental White Eye and Eucalyptus, oil, 14 x 11.

- Sarah Siltala, Pose on a Pear, oil, 12 x 12.

From her current home on a rise just west of Albuquerque, the 47-year-old artist is a two-minute drive from vast expanses of open land, a constant source of artistic and spiritual inspiration. Paintings such as PASSING STORM reflect her approach to the landscape, which draws on memory, feeling, and a lifetime of experiencing the spectacular light, dramatic weather, and immense skies of her home state. “In summer we have these billowing clouds on the horizon, and when the ‘walking rain’ moves across the desert, the light contrasts with the darkness of a storm, and they coexist in the same moment,” she says.

With an ongoing commitment to artistic growth, Siltala enjoys periodically turning her attention to new subjects. This year, for example, she plans to do more landscapes and add serene, uncluttered floral imagery to her still-life repertoire. Yet regardless of what is on her easel, she expresses gratitude for an awareness of art as integral to the fabric of life. “It flows out beyond the studio,” she says. “It’s a lifetime of observing the world and finding beauty in quiet things.”

representation

Sage Creek Gallery, Santa Fe, NM; Mountain Trails Galleries, Sedona, AZ; www.sarahsiltala.com.

- Sarah Siltala, Spring Song, oil, 10 x 12.

- Sarah Siltala, Summer Sweet, oil, 11 x 14.

This story was featured in the January 2019 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art January 2019 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook