Like the figures in his paintings, B.C. Nowlin journeys into the unknown with his art

By Gussie Fauntleroy

This story was featured in the July 2019 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art July 2019 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

IN HIS NEW Mexico studio not long ago, B.C. Nowlin pulled out a partly painted canvas he’d set aside a year or so earlier, when its momentum seemed to stall. In shades of umber, it was to be a field, with other imagery to follow. But like a dream that slips away when the dreamer wakes, the intuitive feeling that initially propelled Nowlin’s brush strokes had faded, so he had stowed the canvas away. When he eventually brought it back out, he was inspired to paint over the original colors in nocturnal tones.

He liked the resulting textural quality and nighttime mood. Then he found himself painting a sprawling, pueblo-like city, fronted by what looks like a massive mission church. As soon as he touched the church’s twin steeples with white, he stopped short. “When I saw the glimmer of the top of the steeple, it almost blew me across the studio,” he says, remembering the charge that came from knowing he’d found the painting’s direction. “I thought, there it is!” He added a bright moon and a procession of figures, some carrying torches as they wind their way toward the city gates.

Like all of Nowlin’s work, MIDNIGHT evolved organically, driven by an impulse within the artist rather than by any preplanned idea or even a drawing or sketch. This particular piece, part of a major solo exhibition this month at Manitou Galleries in Santa Fe, took a while to reveal itself. More often, Nowlin’s first stream of excitement carries a painting to completion in a fairly quick burst. Still, he happily followed the process where it led, as he does with all his art. “It’s like a dream unfolding on canvas. I have only the vaguest notion of which way it’s heading, and when I’m in it, I’m thoroughly inside it. I’m enveloped by it,” he says.

- B.C. Nowlin, Air, oil, 24 x 48.

- B.C. Nowlin, Called by Name, oil, 48 x 24.

- B.C. Nowlin, Midnight, oil, 30 x 40.

As he speaks, Nowlin sits on the patio outside his circa-1890 adobe home close to the Rio Grande in Corrales, NM. His morning ritual—year-round, except in inclement weather—includes riding his motorcycle across the river to a coffee shop where he drinks cup after cup and reads an entire newspaper, chatting with folks before heading to the solitude of his studio. Over the course of a year, the 69-year-old artist logs thousands of motorcycle miles, going to and from the studio and on longer trips.

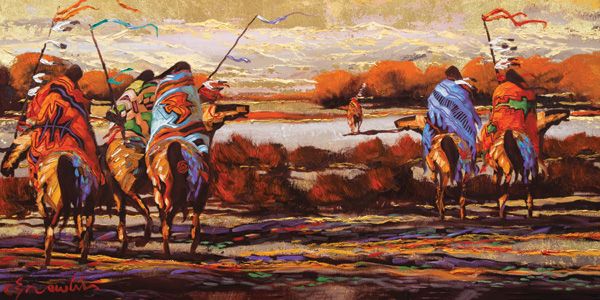

It’s an appropriate activity for someone whose internationally collected paintings invariably suggest a journey. Earlier in his career, Nowlin often depicted figures traveling on foot, in large or small groups or alone. More recently they tend to be on horseback, but always they are seen from behind, and almost always they move toward an unknown, distant point. “I’m not ahead of the viewer” in knowing where the figures are headed, he says. “I haven’t taken a step further into the image than they have. I’m wondering the same thing they’re wondering.”

WHEN IT comes to his own life’s journey, Nowlin could not have foreseen the places his art would take him when he started out. Yet in many ways, his upbringing allowed him to be comfortable with the mystery of the unknown. His father’s highly classified government job kept him tight-lipped about all but the most trivial aspects of his work. Nowlin’s mother was also somewhat inscrutable to her son and two daughters, although with beautiful singing voices and musical and religious inclinations, she and her husband frequently engaged the children in gospel harmonies.

- B.C. Nowlin, Path of Light, oil, 40 x 30.

- B.C. Nowlin, Red Place, oil, 24 x 48.

- B.C. Nowlin, This Path, oil, 60 x 48.

With the family’s property bordering Sandia Pueblo just north of Albuquerque, very close to where he lives now, Nowlin grew up immersed in a tri-cultural world. His mother’s earliest memories were of Laguna Pueblo, west of Albuquerque, where her aunt married into the tribe and Nowlin’s grandparents moved to open a garage on Route 66. Nowlin’s own boyhood friends were primarily Hispanic and Native American. Tales and legends of angels and demons, spirits of light and dark, wove their way through his early awareness, intertwined with the constant daydreams of an easily distracted boy.

In school Nowlin filled the margins of his notebooks with drawings, just barely getting by in his classes. The summer he was 12, he borrowed his sister’s bicycle and pedaled into Albuquerque to an art-supply store. He bought an oil-painting starter kit, pedaled back home, and taught himself to use it, beginning with imagined ocean scenes. By his senior year of high school, he was making a hundred paintings a year. But he was kicked out of art class for what his teacher saw as disobedience because B.C. was unable to stick to the instructions and render only what he actually observed. Instead, he always added a little more: a lightning strike in what should have been a bu-colic landscape; a school bus on a choir trip, but engulfed in flames under a plume of black smoke in the desert sky. (Images of burning vehicles intrigue him to this day; there will be one in the Manitou show.) “The teacher thought I was making fun of him,” he says. “But my imagination always wanted to see more.”

Following high school and a brief stint in the Marines, Nowlin worked various jobs, among them driving trucks and buses, while painting at night. When he was 28, his first child, a 6-month-old son, died. The experience taught him that after such a loss there could be nothing more to fear, and he delved into painting full time. A couple of years later he was working in a studio in Old Town Albuquerque when famed painter R.C. Gorman (1932-2005) walked over from his gallery next door. Gorman invited Nowlin to use the space upstairs from his as a studio/gallery, for free, describing the younger painter as artist-in-residence.

- B.C. Nowlin, And it was, oil, 60 x 48.

- B.C. Nowlin, Dancing Violet, oil, 48 x 36.

- B.C. Nowlin, Emerge, oil, 60 x 48.

The arrangement lasted four years. It offered Nowlin, who had no formal art education, an introduction to art and artists who, along with himself, would soon propel regional art of the Southwest onto the national and international scene. Smiling, he remembers in particular a “funny little man in a black beret” who would come to his studio and talk about art. “I was the last to find out who he was,” he says of famed Chiricahua Apache sculptor Allan Houser (1914-1994).

As the popularity of Southwestern and Native American art began to explode in the 1980s, Nowlin’s career enjoyed a singular boost. At a 1984 show at Cherry Creek Art Gallery in Denver, a collector fell in love with his work and bought everything he had in the show. She wanted to build him a gallery as well, but Nowlin declined. Instead, he told her some national advertising would help. So for two years she paid for a series of full-page ads in Southwest Art.

“That was it—my world changed,” he says. Galleries around the country began asking for his work, and he was able to select the best. Celebrities and musicians became collectors, among them Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin, Tanya Tucker, and Sophia Loren. His art graced album covers and was part of Hollywood sets. Not surprisingly, for Nowlin it was a time of “wild parties, too much traveling, and too many girlfriends. I was restless and had my own demons to chase out,” he says.

- B.C. Nowlin, Front, oil, 48 x 60.

- B.C. Nowlin, Motorcycle Dust, oil, 29 x 48.

- B.C. Nowlin, Realized, oil, 60 x 48.

But he was painting all along. He explored imagery, returning sometimes for years to those series that “had legs” for him. One such series, which continues today in various forms, features a cathedral-like forest of towering trees and autumn leaves. Traveling away from the viewer within this luminous space are figures draped in cloaks. In a piece called THIS PATH, a large vertical painting, two such figures are glimpsed in silhouette within the forest, with the hint of another farther ahead. Their destination is unseen, although it seems to call to the travelers as a diffuse but intensely glowing light through the trees.

While the people in Nowlin’s paintings clearly have a tribal feel, they are not meant to be specifically Native American, he says. Rather, he refers to them as “iconic tribal figures.” The cloaks they wear, when visible, are adorned with symbols of the artist’s own design, and no two are exactly alike. With a deep interest in history and pre-history, Nowlin points out that every human on earth has indigenous ancestry. “We’re all tribal people, far back in the reaches of our soul,” he says.

He views the earthen villages in his paintings in an equally universal way. Although obviously influenced by the architecture and building materials of the pueblos he has known all his life, Nowlin calls them citadels. He imagines them as ancient, sacred cities that await the spiritual traveler, uniting past and future in the greater circle of time. With enormous appreciation for what his life has given him, he sees himself as one of these travelers, carrying a spirit of optimism as his torch. “That’s why there’s always a brilliant place up ahead in the distance, and why the figures face away,” he says. “There’s something up there, and it’s bright and interesting to me.”

representation

Manitou Galleries, Santa Fe, NM; Weems Gallery, Albuquerque, NM; Mountain Arts Gallery, Ruidoso, NM; Anticus Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ; Dick Idol Signature Gallery, Whitefish, MT; Gallery 166 Vail, Vail, CO; Four Corners Gallery at the Tucson Desert Art Museum, Tucson, AZ; www.bcnowlin.com; www.wrightpublishing.com.

- B.C. Nowlin, Release, oil, 48 x 24.

- B.C. Nowlin, Suzeee, oil, 12 x 36.

- B.C. Nowlin, The Cause, oil, 52 x 72.

- B.C. Nowlin, Trail to …, oil, 30 x 48.

- B.C. Nowlin, Triumph, oil, 40 x 30.

- B.C. Nowlin, True, oil, 30 x 48.

This story was featured in the July 2019 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art July 2019 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook