Jerry Markham captures nature’s essence through an uncommon combination of realism and abstraction

By Norman Kolpas

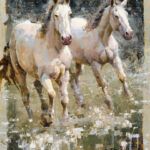

Jerry Markham, Elemental Equine, oil, 30 x 45.

The two steeds appear as in a vivid dream that lingers, their forms softened by the mists of sleep. They are undeniably horses, rendered with unerring accuracy, but touches of abstraction throughout the painting—an undefined setting, broad brush strokes, random splatters around the edges and across the two animals themselves—deepen the impression of a nighttime vision that recedes with wakefulness.

More and more, says Jerry Markham of this recent work, ELEMENTAL EQUINE, “I like leaving things open to interpretation. Some people might see it as a nighttime painting of horses in the moonlight. Others might see them in the fog or the mist. I tried to experiment with how loose I could get it, and to keep out as much detail as possible, to let viewers interpret the horses however they see them.”

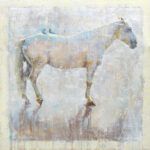

- Jerry Markham, Back Talk, oil, 36 x 36.

- Jerry Markham, Bear Necessities, oil, 30 x 40.

- Jerry Markham, Cleared for Takeoff, oil, 16 x 20.

Such a collaborative experience between painter and viewer has become the very essence of what Markham strives to achieve as an artist. Describing his style, he says, “A lot of people will call it impressionism, while others will say it’s expressionism. To me, what the subject means to me is the impression it makes on me. And when I try to relate that to a viewer, it becomes an expression of how I’m seeing it. So I guess I would fit somewhere in between impressionism and expressionism.”

Such lofty art-world terms are a far cry from Markham’s earliest aesthetic efforts in his native Alberta, Canada. “Like every other Canadian boy, my dream was to be a hockey player,” he laughs. “So when I was around 9 years old, I was always drawing them, mostly goalies.” His other interests at the time were the animals he often saw, sometimes surprisingly up-close, as the child of a fish and wildlife officer for the province. “We got to raise baby bears for about a month,” he says, smiling at the memory. On another occasion, his dad asked him to go down to the basement and fetch some bread from the deep-freeze—which was a ruse to surprise young Jerry with the baby moose that was staying there for a few hours before being brought to a sanctuary after its mother had been killed in a highway accident.

At Bert Church High School in the Calgary suburb of Airdrie, Markham’s artistic talent was recognized by his 11th-grade art teacher, who suggested he apply to study at the Alberta College of Art and Design (now the Alberta University of the Arts). In his first semester there, though, that path struck him as unsuitable. “I wanted to be a painter, but nobody seemed to be teaching about how to mix color”—or any of the other basics of a classical approach to painting. So he left midway through that freshman year.

- Jerry Markham, Crack of Dawn, oil, 8 x 12.

- Jerry Markham, Dressed to Impress, oil, 36 x 36.

- Jerry Markham, Essence of Beauty, oil, 30 x 30.

Instead, he got a job in roofing construction, which paid well and left him with enough resources to pursue painting on his own during evenings, weekends, and the winter months when it was too cold to work outdoors. During one of those winters, he walked into Swinton’s Art Supplies in Calgary to buy supplies and ended up reaching an arrangement with the store’s owner, well-known outdoor painter Doug Swinton, to give him free classes in exchange for hours working at the store. “That,” he says, “is when I really started to learn how to paint, painting figures and still lifes and landscapes, all from life. For sure, it was the turning point.”

Swinton, in turn, introduced him to plein-air painter Jean Geddes, and the two artists together continued to deepen Markham’s education. “What they really taught me,” he reflects, “was how to see. I guess the real eye-opener was realizing how much your brain fills in the gaps, so most beginners paint what they think they see rather than what is actually there. They both taught me that you never want to set out to paint a tree or a mountain. But if you paint this shape, this value, this color, in this place, and then put the next shape and value and color next to it, the result will look like a tree or a mountain.”

He vividly recalls one particular artistic precept that Swinton emphasized. “Doug always used to tell me that you’ve got to paint the apple before you paint the wormhole,” he says, chuckling. That meant that he shouldn’t get stuck on small details at the start of a painting. “‘Bigger brush, bigger brush, bigger brush’ was his whole thing,” Markham says, a maxim that stressed the importance of defining a subject’s fundamental shape from the start. “Even on my smaller paintings now, I’ll start with brushes 3 inches big, just to block in the shapes.”

- Jerry Markham, Ivory Petals, oil, 24 x 12.

- Jerry Markham, Poetry in Motion, oil, 48 x 36.

- Jerry Markham, River Wild, oil, 30 x 45.

One more important mentor helped complete Markham’s education as an artist. He and Swinton admired the work and writings of the late landscape painter William F. Reese (1938-2010), and so they took a road trip to Wenatchee, WA, to pay him a visit and study with him; Markham made return visits for several years. “He taught me more of a philosophy of painting, which was to ask myself the question: Why be a painter at all?” In response to such existential musings, Markham eventually arrived at the simple yet profound realization that painting the world enables him to be more present for it, to appreciate it more fully—and, he hopes, causes that same level of awareness in others. “It seems like people’s focuses are so divided now, staring at their screens, that nobody is present. They always wish they were somewhere else. I’d like my paintings to make them stop and look around.”

Markham’s efforts eventually led to his earliest sales. The first came about 15 years ago when, in his late 20s, he exhibited his work with the Federation of Canadian Artists. Local Calgary galleries began to represent him, along with others in Idaho, and he began participating in shows put on by the Oil Painters of America. A major milestone came in January 2011, when he was invited to the Coors Western Art Exhibit & Sale in Denver—the first of his seven appearances to date in that prestigious annual event. Still more accolades and gallery shows followed.

Along the way, Markham and his wife Leah (they married when both of them were 19, and celebrated their 23rd anniversary in August) moved to the idyllic Okanagan Valley in British Columbia, an area known for its fruit orchards and wineries. They settled on a semirural acre of land where Markham paints in a dedicated studio across the driveway from their house, the window by his easel offering him views of vast Okanagan Lake and pine-covered mountains. Leah, who has a degree in marketing and worked full time during the early years of Markham’s career, now runs the business side of things, from public relations to bookkeeping to working with framers. “Leah and I have an amazing partnership in life,” he says. “I wouldn’t be here without her.”

- Jerry Markham, Trail Rider, oil, 24 x 30.

- Jerry Markham, Western Stature, oil, 30 x 36.

- Jerry Markham, What Are Friends For, oil, 24 x 24.

All around him, Markham finds inspiration for his work, from the brilliant yellow roses Leah grew that he depicts in still lifes to the crows and ravens he often paints. He also travels farther afield in search of subject material, including a trip to a Montana ranch that gave him the idea for TRAIL RIDER.

When he happened to spy a bluebird alighting on the back of one horse, he snapped multiple photos with his Canon camera. Back home in his studio, he chose the precise image he wanted, processed it in Photoshop, and displayed it in high resolution on a large monitor near his easel with a gridline superimposed. That became his point of reference for roughing in the subject on his panel. Then came big, loose washes of paint to define the horse, including drips that add notes of abstraction while also heightening the painting’s dimensionality.

Abstract brush strokes also came into play in his rendering of the field of flowers through which the horse was walking. “I asked myself, ‘How loose can you paint it before it doesn’t look like a field of flowers anymore?’” Indeed, some viewers might swear the horse is actually walking across a stream. “That’s the beauty of it,” Markham adds, “leaving enough room for the viewer to have some input, too.”

As part of his continuing efforts to explore ways of depicting nature’s denizens, right now he’s excited about expanding the size of his images. “This winter,” he says, “I want to do paintings maybe as big as 60 by 60 inches, or even bigger, to see how loosely I can paint animals.” With a note of excitement, Markham’s voice trails off at the thought of the creative challenges, and the dynamic combinations of impressionism and expressionism, that will no doubt result.

representation

Astoria Fine Art, Jackson, WY; Dick Idol Signature Gallery, Whitefish, MT; Main Street Gallery, Park City, UT; Oh Be Joyful Gallery, Crested Butte, CO; Sorrel Sky Gallery, Durango, CO; Art of Man Gallery, Lake Louise, AB, Canada; Gallery Odin, Vernon, BC, Canada; Peninsula Gallery, Sidney, BC, Canada; www.jerrymarkham.com.

This story appeared in the October/November 2021 issue of Southwest Art magazine.