Amy Laugesen’s ceramic sculpture expresses her deep connection with her equine subjects

By Bonnie Gangelhoff

Amy Laugesen, Blue Mud Herd, ceramic/metal, 12 x 12 x 4 each. Photo by Julia Mulligan & Stephen Hume

This story was featured in the March/April 2020 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art March/April 2020 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

Photos by Stephen Hume except where noted.

AMY LAUGESEN remembers a moment early in her career when she learned a valuable lesson: In art-making, expect surprises, sometimes even shocking ones. As a student at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, located in Boston, she was required to submit a project for final review. She settled on creating a life-size sculpture of a horse’s torso made from Styrofoam and plaster, on top of which she applied handmade paper painstakingly fashioned from flax.

On the appointed day, her professors gathered for the big reveal. While they were eyeing the equine, the unthinkable happened: The thin, parchment-like paper started to shrink, shrivel, and make a crackling noise, and a terrible odor wafted through the air—the flax had started to smell like a barnyard. “The sculpture wasn’t meant to be a performance piece,” she says. “But it turned out to be that because the coating shrunk and the piece stunk, and therefore it had kind of a contemporary shock value.”

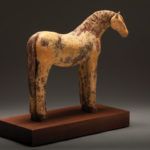

- Amy Laugesen, Denver Artifact, ceramic/mixed media, 13 x 13 x 7.

- Amy Laugesen, Salvation, ceramic/metal/wood, 9 x 20 x 10.

- Amy Laugesen, Sand Wash Mustang, ceramic/wood, 17 x 17 x 8.

The Colorado-based sculptor has long since left behind Styrofoam and flax in favor of clay, her current medium of choice. She also integrates other materials into her ceramic pieces, including steel and wood for bases as well as vintage casters, rusted plow discs, barbed wire, buttons, and other objects.

But the horse remains Laugesen’s primary subject matter and muse. Her trusty steeds range from large-scale public art commissions such as HORIZON, a trio of concrete horses at the Museum of Outdoor Arts in Englewood, CO, to smaller ceramic pieces like SALVATION. The idea for the latter sprung from a wooden pattern that Laugesen salvaged from a foundry on the eve of its demolition. “The pattern arched like a rocker, and it inspired my ceramic rocking horse,” Laugesen says. “I selected a combination of glazes to look like old paint, cracking and peeling from years of use and play as someone’s old toy.”

In fact, the artist is well known for creating works that resemble relics and ancient artifacts. “They inspire me, and my sculptures are created intentionally to appear weathered down to their pure essence,” Laugesen says. “I also relate my sculptures to objects of antiquity in which the extremities—the arms, legs, or head—have been broken off. However, the form, gesture, and spirit of the piece is still recognizable.”

- Amy Laugesen, Sun & Moon, ceramic/metal/wood, 18 x 16 x 7 each.

- Amy Laugesen, Way the Wind Blows, ceramic/metal, 25 x 24 x 24.

- Amy Laugesen, Willow & Dogwood, ceramic/metal, 10 x 8 x 6.

Sue Edmonds, director of Ann Korologos Gallery in Basalt, CO, which represents Laugesen’s work, notes that the sculptor has a special talent for marrying classical forms with contemporary executions. “Amy has mastered techniques to create works that look ancient,” Edmonds says. “She draws from Eastern and Western clay-sculpting traditions and uses a variety of glazing techniques to achieve a unique color for each sculpture. She allows the figure to emerge from the clay, and each figure is born of a different part of history.”

HORSES HAVE appeared in art for centuries, often as symbols of beauty and freedom. Equine images are found in ancient Nordic, Greek, Buddhist, and Native American mythologies. Joseph Campbell, philosopher and author, suggested that mythic symbols like the horse have many meanings and that the use of such mythological symbols in art connects viewers with images from their own dreams and waking life. He believed such universal symbols were rooted in the history of all cultures as well as in the human psyche.

Laugesen echoes similar beliefs when she speaks about her equine artworks. She sees her mission as creating pieces that tell stories about man’s centuries-old relationship with the horse. She also has her own story to tell—one that explains, in part, why she focuses her creative eye on the equine. Born in 1968 and raised in the Denver area, Laugesen struggled in elementary school. Diagnosed with dyslexia in the second grade, her self-confidence declined as the years passed. She recalls asking herself, “What am I good at? I know I am intelligent. But how come I can’t read well?”

- Amy Laugesen, Freewheeling, ceramic/metal/porcelain casters, 19 x 18 x 6.

- Amy Laugesen, Hayden Heritage, ceramic/wood, 14 x 15 x 7.

- Amy Laugesen, Friends, ceramic, 13 x 21 x 5.

One bright spot in her young life was an unbridled passion for horses. Laugesen drew the animals as early as her preschool days. She looked forward to attending Denver’s annual National Western Stock Show and to her family’s trail rides in the Rocky Mountains. By the time she was 10, Laugesen was immersed in riding lessons, determined to save every penny to purchase a horse of her own.

Early adolescence was a particularly turbulent, challenging time. Her worried parents eventually decided to follow up on a doctor’s suggestion to give their troubled daughter a rescue horse. Laugesen recalls meeting the chestnut-colored horse for the first time and experiencing an instant flash of recognition, as if reuniting with an old friend. Soon she was caring for the horse, named Tic Tac, grooming and riding him when she wasn’t in school. The bond was cemented. “I taught him to trust me, and he, in turn, saved my life,” she says. “He needed me. And he was some-one who didn’t care if I could read or not or what I looked like. In taking care of him, I learned to care for myself. His trust in me and his companionship restored my self-confidence and sense of purpose.”

It was a bittersweet moment when the time came to say goodbye to her four-legged soul mate. But she had dreamed of attending a university and was accepted to Marymount Palos Verdes College in California (now Marymount California University) to study graphic design and illustration. In her second year, she came to the startling realization that one-dimensional surfaces bored her. She instinctively longed to be “free and break out” of the flat canvas. Following her intuition, Laugesen began shifting her focus to three-dimensional artworks, and the subject matter that emerged was the horse she had left behind.

- Amy Laugesen, Hayden Heritage (side one) ceramic/wood.

- Amy Laugesen, Hayden Heritage (side two) ceramic/wood.

- Amy Laugesen, Home on the Range, ceramic, 18 x 19 x 6.

In some ways, it should come as no surprise that sculpture was Laugesen’s artwork of choice. Her great-grandfather, Bela Lyon Pratt [1867-1917], was a prominent sculptor and head of the sculpture department at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. While Laugesen was finishing her associate degree in California, her aunt on the East Coast was researching Pratt’s sculptures. He created more than 180 pieces in his lifetime, including the well-known bronze-and-granite female figures that flank the entrance to the Boston Public Library.

Wanting to learn more about her great-grandfather, Laugesen volunteered to help her aunt with research and moved to the Boston area after finishing her degree in 1988. Eventually she also enrolled in classes at the museum school, working in the same sculpture studio where her relative had stood 100 years earlier. Not all of her instructors were encouraging; some advised that she stop fixating on horses “because females sculpting horses was considered a cliché.” But others offered encouragement, saying, “create what speaks to you.” Laugesen agreed. She graduated in 1995 with a bachelor’s degree in sculpture and public art from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University. Missing Colorado and the Rocky Mountain landscape, she packed up and returned to Denver that same year.

TODAY, LAUGESEN works at Durst Studio, Gallery and Sculpture Garden near downtown Denver. Located in a turn-of-the-century brick Victorian house and a repurposed auto shop, the space is home to a dozen artists. When we caught up with her, Laugesen was preparing for the annual Governor’s Art Show & Sale opening in April in Loveland, CO.

- Amy Laugesen, Horizon, concrete/steel, 7 x 16 x 6 feet.

- Amy Laugesen, Lapis, ceramic/wood, 22 x 12 x 5.

- Amy Laugesen, Palouse River Horses, ceramic/wood, 10 x 16 x 10.

The first thing to know about Laugesen’s creative process is that she primarily works from intuitive and tactile memories. On occasion she works from life or a sketch to refine her pieces. “My artistic working process continues to parallel my experience with horses,” she says. “If I am rigid and attempt to control the clay—just like attempting to control a horse—I sometimes meet resistance, have less success, and my pieces blow up in the kiln. It’s a humbling process. It’s about partnering, being in the moment, and staying open to what is being revealed.”

The inspiration for BLUE MUD HERD, which was on view in January at the annual Coors Western Art Exhibit & Sale in Denver, was her recent discovery of a new cobalt-blue glaze. She envisioned a herd of seven horses using this glaze, which resembles dried, cracking mud. Each horse was built by hand in her favorite clay, created in relationship to the others but with its own unique gesture and personality.

The herd was fired in a kiln twice. First the sculptures were fired at a lower temperature to convert the clay into a more durable and porous state to accept glaze. After the glazing process, the herd was fired once again. “After successfully surviving two firings, each horse was mounted to a steel base inspired by museum artifact mounts,” Laugesen says. “The design of the bases allows for the pieces to be configured close together and rearranged in different formations.”

- Amy Laugesen, Pleasure Horse, ceramic/metal/wood, 19 x 14 x 7.

- Amy Laugesen, Rustic Mare (detail), ceramic/steel/wood, 23 x 25 x 10.

- Amy Laugesen, The Yampa, raku ceramic/bronze, 8 x 24 x 5.

There is a reason Laugesen chose to create a herd of seven. Seven is a powerful number in numerology and cross-culturally, she explains. In addition, “aesthetically there is a visual power to a group of seven individual sculptures coming together to create a singular piece. The herd becomes a community, or visually, an abstract formation. For me, the herd of seven horses forms a landscape, a flowing river, or a mountain range.”

Laugesen says that, although she tries, it’s sometimes difficult to express in words her “profound connection to the form and essence of the horse.” “There is an ancient human-and-horse relationship that intrigues me,” she says. “Civilizations before me have explored object-making and painting in the attempt to convey this animal’s spirit and to pay reverence to its beauty and its meaning in their culture. I stand on their shoulders.”

representation

Ann Korologos Gallery, Basalt, CO; Columbine Gallery, Loveland, CO.

- Amy Laugesen, Zach, ceramic/wood, 15 x 16 x 6.

- Amy Laugesen, Zephyr, ceramic/metal, 25 x 22 x 14.

This story was featured in the March/April 2020 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art March/April 2020 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook