Stephanie Hartshorn is inspired by architecture and her love of old things

By Gussie Fauntleroy

Stephanie Hartshorn, Flatbed & Ford, oil, 24 x 36.

This story was featured in the December 2016 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art December 2016 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

One of the first times someone took note of Stephanie Hartshorn’s artistic talent was in a first-year engineering program at the Colorado School of Mines in Golden. Hartshorn (pronounced HART-sorn) had an interest in art but didn’t see herself as “artist material.” She was more comfortable with her analytic, detail-oriented side, her “geek mind,” as she calls it. So following high school in her hometown of Colorado Springs, she headed in a distinctly left-brained direction.

Yet during her first semester at the School of Mines, in preparation for drafting lessons, a professor had his students do freehand drawing using the book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. When he saw Hartshorn’s drawings, the professor pulled her aside. “If the engineering thing doesn’t work out for you,” he told her, “you should consider the arts.” She was stunned. “I loved hearing it, but I really thought he was from Pluto to say that to me,” she remembers, laughing. “I had no confidence in my drawing skills.”

The professor was right in guessing that Hartshorn might not stay in engineering. After a year and a half she changed schools and went into architecture. He had also been able to see something she could not at the time: She possessed inherent artistic talent and a creative side that could be harnessed to work alongside her love of problem-solving. The two halves of her mind found satisfaction during almost a decade of work as a professional architect in the Denver area. Later, when the need for personal creative expression wiggled its way to the front of her attention, she discovered, to her delight, that in painting, just as in architecture, there is a place for her inner geek. She also found that others were pleased by the results of her fascination with form, structure, color, line, the patina of time, and the hint of stories hiding in old things. Even before she left architecture, a major Denver gallery was selling her paintings.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Swizzlestick 5, DunRovin, oil, 24 x 12.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Steel Wheel, oil, 48 x 48.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Rural Roadtrip, oil, 12 x 36.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Plains Red, oil, 20 x 24.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Jackson Howdy, oil, 30 x 40.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Afternoon Repose, oil, 12 x 16.

It was curiosity about the story embedded in old objects that first sparked Hartshorn’s imagination. Growing up just a walk or bike ride away from her grandparents’ house, she often found herself in their basement, which was infamous in the family for the quantity of interesting things packed into it. There she would spend hours picking up objects they had collected over the years, looking at, holding, and playing with them. Whenever she visited anyone’s house, her eyes were drawn to the things they surrounded themselves with. “I was a shy kid, and maybe that was my way of getting to know people, to take in what they had in their homes,” she muses. Sitting in her studio in the RiNo industrial area of downtown Denver, the artist is surrounded by vintage found objects from her own collection—an old measuring scale, a nut chopper, and a round-topped, midcentury Juice-O-Mat. As with the things she wondered about as a child, each object is not only visually pleasing in its color and form but also imparts the suggestion of a narrative, a hint of its life along the way. “I don’t need to know the actual story. You just sense a story within an object,” she says.

Even the building where Hartshorn creates art, Ironton Studios, tells the tale of an earlier time. Metal walls and fabricated steel speak of the building’s role in the city’s industrial past, even as newly developed cafés, breweries, and live/work spaces fill the district with renewed vibrancy. “It was one of those fateful situations,” the artist marvels, relating how in April 2016 she found the space after outgrowing her small studio attached to the garage at the home she shares with her husband and two teenage daughters. “I told one person I needed a studio, and the next thing I knew, here I was,” she says. One way the space answers a desire Hartshorn had not quite articulated at the time is that she shares the building with artists working in a range of mediums and genres, many of whom are active in the contemporary art world. Although her paintings are representational, Hartshorn is drawn to a contemporary aesthetic and intrigued by abstract art. “To be around these other voices is a very powerful environment for me. I believe my art will grow in ways it wouldn’t otherwise,” she says. “This studio felt like a gift.”

Interestingly, two-dimensional art was barely on Hartshorn’s radar as a girl. One summer during elementary school, she signed up for classes at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center’s Bemis School of Art. Painting “didn’t stick,” as she puts it. But the following two summers she put her hands to clay and fell in love with the tactile, sculptural experience. Later when she found her niche in architecture at the University of Colorado at Boulder, she was strongly influenced by the idea of buildings as “life-size sculpture” that can powerfully affect those living and working inside them. Her mind also enjoyed the absorbing challenge of working out countless details to produce a design that fills diverse needs and fits prescribed parameters. Among the most rewarding designs she worked on were new educational facilities and projects involving historic preservation—revitalizing an aging structure while incorporating and honoring its past.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Just So, oil, 16 x 12.

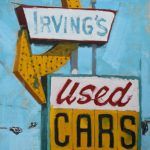

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Irving’s, oil, 48 x 24.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Ela Crisp, oil, 24 x 30.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Steel Ribbons, oil, 24 x 24.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Barn Grass, oil, 24 x 48.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Urban Escape, oil, 30 x 24.

Still, at some point another pursuit, surprisingly, began tugging at Hartshorn’s attention. She wanted to paint. When her first daughter was born, she took a leave of absence from architecture, thinking it would be for six months. It turned into six years, during which time her second daughter was born. Engaging her young children in the natural activity of art reminded her of her own creative side. She took a painting class with Chuck Ceraso at the Denver Art Museum and fell in love with oil paint, recognizing in it qualities she had enjoyed with clay: the medium’s viscosity, the way it can be pushed and pulled, built up and sculpted down. In painting she also discovered similarities with architectural work. “Both are big puzzles—how are you going to connect one thing to another? They’re both about problem-solving,” she says. During a weeklong painting workshop at Ghost Ranch in northern New Mexico, everything clicked into place, at least on an internal level, although it took a few years for outer circumstances to catch up to her dream of full-time fine art. During that time she studied at the Art Students League of Denver and with painters Kevin Weckbach and Mark Daily.

Today Hartshorn’s artistic process reflects a modernist concern for the surface qualities of an image and an unconventional approach to applying paint. More frequently than not, she paints with a board or panel flat on her worktable, where she can turn it around in any direction as she very deliberately moves paint, focusing on the board’s surface as she does. “Working flat, I feel more engaged with the painting in some way; it feels more tactile, like creating a sculpture—like constructing it,” she says. She can hang a painting on a pegboard on the wall to study it, but viewing it from various angles as she works provides fresh perspective. “Your eyes get settled into things, and they tell your brain it looks a certain way,” she says. “It’s important to challenge that and make sure I see things I otherwise couldn’t.”

Really seeing an object’s shape is part of what draws Hartshorn to vintage and neon signs, including the iconic bucking bronco on top of the Million Dollar Cowboy Bar in Jackson, WY. Rendering the sign in the painting JACKSON HOWDY, she found herself fascinated with the constantly changing edges between the sign and the blue around it, and with the feeling of movement in the neon tubing. In this piece, as in much of her work, she engaged in a little “guinea pigging” with some parts of the process, not knowing if they would work out. They did.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Mini Trike, oil, 5 x 7.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Golden Connection, oil, 24 x 36.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Swizzlestick 6, Red Pine, oil, 24 x 12.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Take Flight, oil, 24 x 36.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Top Star, oil, 36 x 24.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Watkin’s Whites, oil, 18 x 24.

STEEL WHEEL, depicting an enormous Ferris wheel with a gold-starburst center, reflects Hartshorn’s enthusiasm for abstract art and the way static-seeming lines can be given dynamic energy. The piece also took her back to her architecture days, as she wrestled with figuring out the giant wheel’s structural form, part of which was obscured in her reference photos by palm trees. “It was thoroughly exciting to me, because there was so much going on within the wheel and the way that structure is breaking up space,” she says. The striking result effectively conveys the magnificence and thrill of the ride itself.

Recently Hartshorn has begun learning more about her ancestors, great-great-grandparents who came from Germany to homestead on Colorado’s eastern plains. Discovering she is a fifth-generation Coloradan with a ranching heritage rather than fourth-generation, as she’d previously thought, helped the artist understand her longtime appreciation for rural America and what it contributes to our way of life—and also explains why aging barns, tractors, and other reminders of simple rural life show up frequently in her art. Like fading signs, historic buildings, and vintage objects, these images offer “beautiful structures, shapes, colors, and designs,” she says, “and there are beautiful stories in there.”

representation

Evergreen Fine Art, Evergreen, CO; Sorrel Sky Gallery, Santa Fe, NM; Abend Gallery, Denver, CO.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Morning Harvest, oil, 24 x 30.

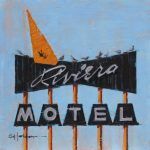

- Stephanie Hartshorn, No Vacancy, oil, 12 x 12.

- Stephanie Hartshorn, Coupled, oil, 24 x 60.

This story was featured in the December 2016 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art December 2016 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook