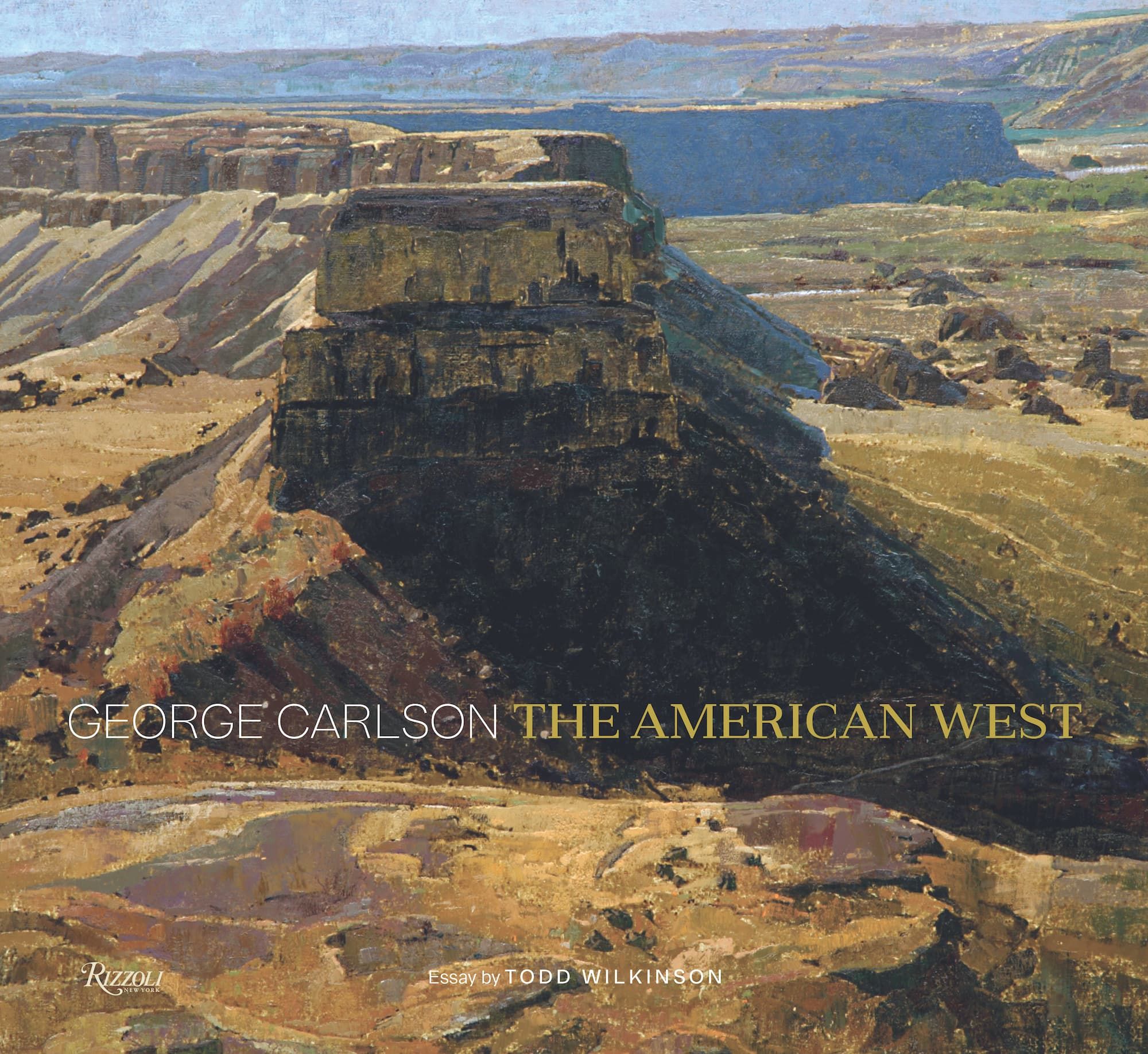

A stunning new book celebrates the life and work of artist George Carlson

Renowned sculptor and painter George Carlson—the only two-time winner of the prestigious Prix de West, the highest honor in the western art world—is the subject of a new coffee-table book out this month from Rizzoli titled George Carlson: The American West. The first comprehensive book on Carlson’s work, it chronicles his journey from his boyhood in Illinois through his early days as an illustrator, his explorations of the people and land of the Southwest, his enormous success as a sculptor, and his late-career return to painting. An essay by Todd Wilkinson traces that story and is excerpted here with permission. We pick up the narrative at the turn of the last century, when Carlson began to shift his attention from bronze to paint.

Renowned sculptor and painter George Carlson—the only two-time winner of the prestigious Prix de West, the highest honor in the western art world—is the subject of a new coffee-table book out this month from Rizzoli titled George Carlson: The American West. The first comprehensive book on Carlson’s work, it chronicles his journey from his boyhood in Illinois through his early days as an illustrator, his explorations of the people and land of the Southwest, his enormous success as a sculptor, and his late-career return to painting. An essay by Todd Wilkinson traces that story and is excerpted here with permission. We pick up the narrative at the turn of the last century, when Carlson began to shift his attention from bronze to paint.

In 2002, George Carlson had a solo exhibition at Nicholas Fine Art in Billings, Montana, which was centered on a series of horse pieces. That was one of the last major solo exhibitions Carlson did as a sculptor. The Seattle stone carver Tony Angell said many were puzzled when Carlson walked away from sculpture. “He was doing these remarkable interpretations of human and nonhuman forms in bronze. Each one had such gravity and placement, like they were just getting on with what they were destined to become,” he said. “So few artists ever reach that place of command and originality, so I was surprised when he unceremoniously finished that part of his career and strived to do the same thing with a brush.”

Today, when contemplating Carlson’s landscapes, there is no separation from what he started doing more than 60 years ago, interpreting and exploring the form. “George continues to delve into his own relationship with the earth,” Angell said. “The way he seeks to understand organic forms is no different than if he were taking on a human or animal figure.”

- George Carlson, Wyoming Badlands (2017), oil, 42 x 42.

- George Carlson, Dragon Sky (2017), oil, 38 x 42.

- George Carlson, Umatilla Rock (2011), oil, 42 x 42.

In the years after the start of the new millennium, while delivering sculptures to a foundry in Oregon, Carlson became more interested in the Palouse and Channeled Scablands landscapes of Washington. Sometimes he would bird-watch on the edge of them, but then he began to photograph and sketch them. Ideas for compositions started visiting him in his dreams.

“For a number of years I would take a plane from Spokane to Seattle for a connecting flight,” Carlson said. “When I had a window seat, I always enjoyed looking at the land below. Eastern Washington, from the air, is mainly broken up into varying shapes of agriculture or miles of arid terrain. But there was one spot that interrupted this broad plain of high-desert landscape. Just before the Cascade Mountain range became visible, there was a dramatic gash in the land. Once I became aware of this location, I had to find out what caused it. I looked the area up on a topo map and discovered the gash was called Dry Falls.”

In reading about the geology of Dry Falls, he was intrigued. “I took a road trip over to investigate it as a venue for painting research, and it was love at first sight,” he said. “There was a solid, stalwart ruggedness to this parched land made up of deep canyons and sheer basalt cliffs. I was captivated by the various light and shadow effects.”

Carlson did not want to make an impetuous or casual return to painting. He needed to retrain his observational powers, which had grown rusty. He spent lengths of time peering into the terrain to assess values and color harmony, spatial presentation, and how his eye moved through it. “I had made paint charts at the American Academy of Art 60 years earlier, but when I returned to painting years later, I realized they weren’t of much use because they weren’t carefully done,” Carlson said. “By redoing them, I made sure to get the most potential out of each color in the greatest variety. Developing those color charts helped me break free from the formula approach to painting where it becomes easy to rely on certain colors repeatedly.”

Carlson’s landscape paintings are renowned for their tonalism and sophisticated approach to color value, especially in low light or evening conditions. “When I was taking color notes from the charts out in the field, by careful comparison I could get a close match, and I realized I may not have picked that color without this aid,” he said.

- George Carlson, Sentinel Bluffs (2008), oil, 36 x 43.

- George Carlson, Northern Light (2015), oil, 32 x 42.

- George Carlson, January Thaw (2013), oil, 42 x 32.

Carlson explored the Scablands and the Palouse in a four-wheel-drive truck, inching down steep, hair-raising terrain to get to some of the more remote interesting places. “Once I’d driven into places that were accessible by truck, I then liked to get out and hike. Hiking gave me that intimacy with the land that I didn’t feel while driving. I spent days hiking in remote areas, never predetermining a painting, just being open,” he said. “When I came to a place that spoke to me, I would sit quietly for a while to see if all my sentient powers were simpatico with the visual. When my attitude was one with the land, this rush of exhilaration opened me up and brought the forms of the surrounding landscape into sharper focus as I saw the possibilities for beauty.” From these forays, and about a dozen easel paintings, emerged the award-winning UMATILLA ROCK.

As word of Carlson’s surprising decision to begin submitting paintings to major shows spread, there was buzz in the art world. The artist didn’t try to make a big deal about it, but his works were so different from other Western landscapes and so well executed that they commanded attention and won awards, most notably honors bestowed by his peers.

Carlson does not identify as an iconoclast, though his influence in inspiring dozens of other daring contemporary painters and sculptors in the West is undeniable. He derives pleasure from the friendships he has cultivated with those of younger generations and loves passing on insights about the philosophy of art.

Born and raised in Wyoming, the painter T. Allen Lawson regards Carlson as a philosophical mentor on art. Considered one of the premier realists of his generation, Lawson received formal classical training in Chicago and at the Old Lyme School in Connecticut. Like Carlson, he received critical recognition early. In 2017, Lawson won the Prix de West Purchase Award, joining Carlson in that rare company.

“The secret to my friendship with George is that I’m extremely lucky he’ll have me as an acquaintance. He is a genius,” Lawson said. “His work embodies everything I admire. It’s representational, but it’s not. It’s simple, but it’s not. It could easily be seen as total abstraction. There is a mystery to it, and it holds a spiritual essence that forces internal reflection. Nobody that I’m aware of in this country is on the same level as George. He stands alone.”

According to Lawson, realism is a term that’s misleading. Carlson creates representations of real people, places, and things that are recognizable to a viewer’s eye and need no interpreter, but the image itself is actually a convergence of abstraction that reads differently depending upon where one is positioned in a room. Leaning forward, examining the application of individual brushstrokes inches away, the surface appears as a whir of color and texture, the larger scene indiscernible. But stand back, and every line and mat of paint snaps into place, the whole of George’s vision right there in front of the viewer.

The ability to facilitate such visual alchemy is not about how one applies paint, but how the world is perceived and processed through the brain to conjure the illusion. It is the opposite of a literal translation, although a viewer might believe it is an exacting image. Carlson’s fidelity as an artist is to faithfully illuminating the spirit of a subject, offering it more than superficial treatment.

Bend down on a knee to surveil the underbrush beneath a forest canopy that is set on a foothill above a river valley, and one—especially if one is George Carlson—will understand how important little parts of nature are, how they collectively inform what appears before us as the essential whole. Certainly one may read the above, or gaze at a Carlson work in a museum, and conclude that such intricate knowledge doesn’t really matter. “But it matters to George,” Lawson said.

We as viewers may not always be aware of the extra dimension. The empathy Carlson holds for the little things is insinuated and celebrated in the harmony, choice of color, and minute differences of value in shadow. A dab of paint may reference a mat of centuries-old lichen on a glacial erratic, or the demarcation point between metamorphic and sedimentary rock formations, or a bird whose song Carlson heard every time he passed a certain spot at the marsh. Like a composer interjecting a sweet flash of oboe into a composition, nearly indetectable amid the sonic flood of a symphony, the dab of paint is there, and, in a way, it is one of the elements that make all the difference—singular, well-placed notes in a musical score playing the same role as brushstrokes.

This story appeared in the October/November 2021 issue of Southwest Art magazine.