Mark Andrew Bailey tells human stories of energy, movement, and life

By Gussie Fauntleroy

Mark Andrew Bailey, Bottles and Bowties, oil, 40 x 50.

What does an artist do when all access to his chosen subject matter shuts down for more than a year? Urban restaurants and bars were the primary source of inspiration for Colorado painter Mark Andrew Bailey’s impressionistic imagery—until coronavirus restrictions closed all those doors. He felt a definite sadness, not just for himself but especially for the workers in the service industry who were out of their jobs. But Bailey found that having to step back for a while also provided an unexpected opportunity to reflect on his art. “Without the same subject matter, I had to ask myself: What do I want to paint? What am I trying to say? I realized I want to touch more on the human story,” he says.

To find this new material, Bailey began sifting through the immense library of photos he has taken over the years. But instead of creating his usual complex, multifigure compositions, he pulled out and focused on single individuals. The small painting titled SIP, for example, captures the moment when a man in a light-green shirt puts his lips to a paper cup of coffee. “I was taking a picture of something else, and this guy happened to land in one of my shots,” he says, recalling a morning spent wandering through a New York City farmer’s market years ago. “I like candid shots. I want honesty, I want authenticity, people being natural,” he adds. These qualities are part of the larger scenes he paints as well. But unlike most of his work, the background in this piece is purely abstract, while still expressing the vibrant energy and movement for which he is known.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, Sip, oil, 12 x 12.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, Daniel’s Kitchen, oil, 40 x 50.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, Ambience, oil, 40 x 40.

“In some ways I’m circling back to how I started out: experimenting,” Bailey says. “Some of it may not see the light of day, but it’s very fulfilling. It’s a nudge to tap into my inner artist and be less concerned with what people expect.” SIP was part of a fall 2020 solo show at Abend Gallery in Denver, and the public’s response confirmed for the artist that exploring new directions, while maintaining the essence of his creative vision, is well worth the time: The show sold out.

The 39-year-old artist has circled back in other ways as well, relocating to his home state in 2012 after several years on the West Coast. His return was followed by an enormously satisfying event: In 2015 he was juried into the Governor’s Art Show in Loveland, CO, the community where he grew up. Exhibited alongside the work of top artists in a state that nurtures exceptional talent, his painting won Best of Show. The award reinforced his belief that he was in the right place, both geographically and artistically.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, Kitchen Color, oil, 16 x 12.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, O-KU, oil, 48 x 36.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, Lemons, oil, 18 x 14.

Looking back, Bailey sees ways in which his creative journey began under auspicious circumstances that seemed normal in a young boy’s mind. Both of his parents, an engineer/consultant father and a mother caring for three children at home, took drawing and painting classes and had a strong appreciation of fine art. “They were both quite good,” he says, remembering in particular his father’s watercolor landscapes and a pencil drawing his mother did of the family’s dog. Even just driving around town reinforced the importance of art. With world-class bronze foundries, sculpture gardens, and an emphasis on public art, Loveland was an immersive art experience long before he was aware of its inspirational effects. He smiles at the memory of seeing his hometown in a new light after moving away. He remembers thinking, “Whoa, all these other towns don’t have a bronze sculpture on every corner?”

In a more formal venue, every summer the family attended the Governor’s Art Show at the Loveland Museum, where Bailey was exposed to the work of such greats as Quang Ho, Kim English, and Ron Hicks. “That was one of the first seeds planted in my teen mind, that these guys were making a living at this, so it was a legitimate, viable pursuit,” he says. Yet even though his own drawings and paintings brought praise, and his parents encouraged him to pursue his love of art, other voices edged their way into his thoughts. A couple of high-school teachers attempted to steer him in the direction of graphic design, while friends and other nonartists sowed doubt about a career in fine art.

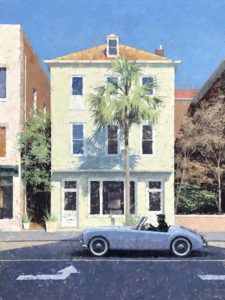

- Mark Andrew Bailey, Sunday Drive, oil, 40 x 30.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, Reverie, oil, 36 x 24.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, Sundown on Leon’s, oil, 30 x 24.

As a result, when he entered the Academy of Art University in San Francisco, it was to study animation. Fortunately, every student was required to complete two years of intensive foundational art instruction, including anatomy, perspective, figure drawing, color, and design. Within the first couple of semesters, Bailey took an oil painting still-life class—and loved it. Meanwhile, in a 3-D animation course, he found himself sitting for endless hours in the animation rendering lab, waiting for the computer program—glacially slow by today’s standards—to process every gesture and movement and facial expression he drew for even a short animation assignment. “I was thinking, I don’t really want to sit in a lab for the next four years. I want to be drawing and painting,” he says. When one of his first still-life paintings was juried into the academy’s annual student show, which was very competitive, he knew it was time to switch directions. He turned to illustration, opening the door for expressing emotions and stories through the human form.

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in illustration, Bailey took a graphic design and illustration job in Portland while continuing to paint on the side. He began showing his paintings in a gallery there, then added a Charleston, SC, gallery after visiting the southern city for a wedding. Soon other art spaces asked for his work. By 2012, after moving back to Colorado and maintaining the commercial art job remotely for a year, he was ready to put all his effort into fine art.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, Beausoleil, oil, 40 x 50.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, 13th, oil, 36 x 48.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, B&B, oil, 36 x 48.

While his subjects today range from street scenes to still life, with occasional broader cityscapes and landscapes, the settings most compelling to him are busy urban restaurants, coffee shops, and bars. These interior spaces incorporate all the elements he loves to draw and paint: the human figure, suggestions of narrative, the energy of a bustling scene, architecture, interior and graphic design, and variations in color and light. “Restaurants spend a lot of money on interior design and atmosphere, so they’re like a stage set up for me as an artist,” he says.

He also offers a nod to the culinary arts and those who work in that industry. Until the relatively recent trend of food as entertainment with the Food Network and celebrity chefs, men and women spent years training and perfecting their kitchen and serving crafts without much public acknowledgement. “There’s an experience created for you in the service industry, but you don’t know what goes into it,” Bailey says. “Viewers relate to the diners in my paintings, but I like to also focus on the servers, the line cooks, the person putting out place settings. They’re often overlooked, but painting them can make for a beautiful moment.”

One such moment led to what the artist sees as a subtle but important stylistic shift in his work. At the bar in a Chicago restaurant one early evening, cool light from outside was melding with the warmer tones inside, while the hard lines of architectural elements contrasted with the movement of bartenders and waitstaff behind the bar. As he painted APÉRITIF, Bailey found himself inspired to translate the atmosphere through a somewhat softer and more varied mark-making approach than he would have used in the past. Previously, he tended to abstract the background through almost frenetic marks of color that resulted in fractal or sharp-edged pixelation, creating a strong impression of movement and even the suggestion of chatter and noise.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, Mixer, oil, 20 x 20.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, Apéritif, oil, 36 x 36.

- Mark Andrew Bailey, Market Maker, oil, 12 x 12.

With this piece, though, he thought of something a painting instructor had once said, that mark-making should be like jazz music. Each touch of brush to canvas can convey a different kind of note—quick and staccato, or resonating and long. The confident artist lets the paint decide how it will land and develops the work from there, Bailey says. APÉRITIF began with intensely energetic marks, almost in an abstract expressionist mode. Then he went back and judiciously determined how much of that feeling to leave in and how much to refine. This stage of the process engages his intuitive and analytic sides, both of which are well honed. “I’m deciding, will this mark enhance the piece or potentially kill it,” he says. “The final work looks energetic and raw, but each individual little shape and color is designed.”

Against this backdrop Bailey uses fundamental artistic skills of perspective, compositional structure, light, and anatomy to add realism and the human narrative. He calls APÉRITIF “a moment in my growth as an artist,” where the relationship between abstraction and a tighter approach felt especially satisfying. In earlier phases of his career he might have pushed the abstract in one painting and pulled back in another. But here was the sweet spot. As he puts it, “It’s the balance between what I appreciate about abstract art and just the quality of paint, and draftsmanship and drawing.”

representation

LePrince Fine Art, Charleston, SC, and Naples, FL; Abend Gallery, Denver, CO; www.baileypaintings.com.

This story appeared in the June/July 2021 issue of Southwest Art magazine.