Michael Workman paints nature’s simple truths

By Elizabeth L. Delaney

This story was featured in the June 2016 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art June 2016 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

Truth, beauty, and goodness: These are the broad, subjective, and sometimes discounted concepts that form the foundation of Michael Workman’s paintings. Workman’s landscapes are idyllic; they depict the visual splendor of the American Southwest in colorful vistas, sunlit mountains, and far-reaching fields peppered with cattle. At the same time, his scenes convey a deeper meaning, one that simmers just under the surface, slowly escaping from among the layers of oil paint and intricate brushwork. Workman does not endeavor merely to paint an appealing picture, but also to share the spiritual connection he feels to the land and throughout his own life. “I’m a believer, and I believe there’s a purpose behind this existence,” he says. “I want people to slow down, to stop and look at how beautiful this world is.”

Workman’s spirituality is an essential element of his artwork, informing not only his subject matter but also the perspective from which he paints it. He views the artist as the vessel for a higher power, blessed with the ability to reveal the empirical beauty within the land, as well as to harness the spiritual forces that sustain it. Like 19th-century landscape painter George Inness, Workman holds that nature is a manifestation of the divine. As a result, a nature-inspired work of art is something to be felt, not just observed. “Inness was spiritual and also very contemporary for his time,” says Workman. “Like Inness, I hope my work communicates that there’s something below the surface.”

Workman describes himself as a contemporary traditionalist, embracing the historic aesthetics of the western canon while simultaneously infusing his works with elements of abstraction. This juxtaposition of styles highlights Workman’s interest in mining contrasts, both on the canvas and in his creative process. These contrasts are, in fact, the hallmark of Workman’s oeuvre. They engender a balance, allowing his work to straddle the line between romantic and modern, and between bold and demure, as it engages viewers on visual and emotional levels.

Aesthetic contrasts function as accents in Workman’s compositions: a swath of intense pigment amid more understated colors, bright light next to shadow, or a few thickly painted strokes among the smooth, gauzy areas of color. These divergences are subtle in their drama, however, evoking the sense of harmony the artist tries to achieve across his canvases. “One thing that is consistent in art history is the opposition between different ideas—contemporary vs. traditional, romantic vs. classic, naturalistic vs. abstract. I decided years ago not to choose between the opposites, and instead I work to bring them together in a beautiful way.”

The timeless adage to paint what you love rings true for Workman, who says simply, “I love an expansive landscape—the expanse of the West.” The majority of his subject matter reflects this deep-rooted affection, and although he has traveled across the country and abroad, inspiration most often materializes within the vast natural area that surrounds his home in Spring City, UT, where he has lived with his wife, Laurel, and their five children for more than two decades. He feels a spiritual connection to this bucolic place, which he visited as a child with his father and photographed as a young artist seeking potential subject matter for his earliest paintings.

Growing up on a small farm in rural Utah, Workman was surrounded by the rugged, sprawling geography that today populates his paintings. He felt a bond with the land, along with a calling to draw and paint it, but like many other artists, he never considered fine art as a viable career path. He was fortunate to have talented, supportive teachers throughout grade school and high school, though, and continued his artistic pursuits into college, where he eventually declared fine art as his major. By the time he was finished with higher education, Workman had earned both undergraduate and graduate degrees from Brigham Young University.

Early in his career, Workman was employed as an architectural illustrator, and through the years he has continued to benefit from the technical skills and discipline he learned in the field of applied arts. “I go to work every day,” he says, describing his life as a painter. He considers his art-making a “painful but joyous process” that demands passion along with tenacity, and he appreciates his time as an illustrator for teaching him to draw on that structure. “The work comes first, and then the inspiration. It’s about plugging away until you unlock the magic.”

Workman’s creative process is hands-on from beginning to end. He explains, “The process begins long before the actual painting.” He takes great care to thoughtfully steer every aspect of the progression, from photographing his subject matter to mixing colors, painting, and then editing each composition. In this manner, Workman can ensure both the visual and structural integrity of his paintings, for which he stretches linen or muslin over plywood panels.

Workman’s fresh, somewhat impressionistic paintings belie their initial look of spontaneity, in that the artist does not work en plein air. He likes to paint specific, sometimes fleeting moments in time, such as an especially vibrant sunset or the quiet stillness just before sunrise, but he finds trying to capture this type of subject matter on-site too hurried, even restrictive. He prefers a more measured approach and instead builds his compositions through a combination of photographs and memories of his experiences in the field. He then utilizes his studio not only as a place to paint but also as space in which to ponder the imminent artwork and get a feel for it as it emerges. “I love the controlled environment of the studio,” he says. He notes that this method of working allows him to fully develop his ideas and do justice to the subject matter he so keenly respects.

Workman paints thoughtfully but instinctively, without preliminary drawings or sketches. He applies pigment in layers—painting, scraping, sanding, and then repainting—to build complex, sumptuous surfaces. Yet despite their considerable texture and evident brushwork, as a rule, Workman’s canvases remain smooth. Thinly applied strata of paint and glaze fuse together to create a sense of depth that is further refined by a delicate sheen.

Working with a limited color palette, Workman has often been described as a tonalist. He explains that while he did not consciously set out to earn that label, ultimately he has found that a restrained palette allows him to achieve the placid, effervescent quality he wishes to extract from the paint. He starts with primary colors and mixes additional hues as he works, once again taking a hands-on, controlled approach to his art-making.

Through his paintings, Workman attempts to stimulate a dialogue with nature and its intrinsic, potent beauty. He invites viewers not only to gaze at the pigment, light, and imagery on the surface but also to absorb the energy that emanates from below. He seeks to convey the passion and excitement that result from realizing that the sum of the parts evokes the greatest emotional intensity. Workman creates this discourse as he composes each piece. It continues through his painting and editing process, persisting until the painting transcends his own vision and drives the process itself. This is the moment of creative catharsis for Workman, where the work directs its own course, unconstrained and free of his preconceptions. “The real magic starts to happen when the conversation is between you and the painting,” says Workman, who strives to interact with his medium on a higher level, channeling his spirituality and approaching the sublime.

Recently, Workman has entered a transitional phase in his work, challenging himself to take his method of communicating truth and beauty to the next level. Recalling such contemporary masters as Mark Rothko, Richard Diebenkorn, and Gerhard Richter, Workman is beginning to deconstruct his surfaces, producing an increased sense of movement and energy and making the subject matter more universal. He has expanded his exploration of the ways abstraction can emphasize the formal, fundamental elements of the landscapes he paints. Several of his most recent compositions feature these variations, marked by a reduction of detail and spatial compression. Additionally, Workman is dissecting his backgrounds, revealing the canvas underneath and emphasizing the tactility and “objectness” of the painting.

Whatever visual changes Workman may choose to explore, the thematic threads running through his body of work remain constant: the pursuit of beauty in a culture that often overlooks or denies its presence. “My watchword is beauty,” he explains. “It is not difficult to see that we live in a world that is full of turmoil. On the other hand, it is easy to be tempted by the cliché. Rather than choose between angst or picturesque beauty, I hope to offer a reminder that there is beauty in the ordinary. My statement is simple: There are still good things.”

representation

David Ericson Fine Art, Salt Lake City, UT; Gallery 1261, Denver, CO.

This story was featured in the June 2016 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art June 2016 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

- Michael Workman, Fredericksburg, oil, 11 x 11.

- Michael Workman, Jersey Sketch, oil, 8 x 8.

- Michael Workman, Loafer, oil, 30 x 60.

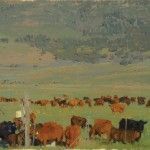

- Michael Workman, Red Angus, oil, 18 x 20.

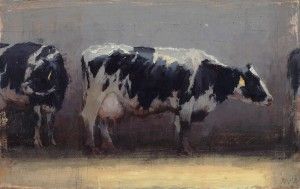

- Michael Workman, Dairy 3, oil, 6 x 16.

- Michael Workman, Dairy 4, oil, 7 x 8.

- Michael Workman, Estuary, oil, 7 x 11.

- Michael Workman, Dairy, oil, 6 x 10.

- Michael Workman, Summer Pasture, 8 x 15.

- Michael Workman, Mountain With Evening Light, oil, 11 x 11.

- Michael Workman, Clouds, oil, 8 x 8.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook