Georgia’s Booth Museum captures the essence of

the West through the eyes of contemporary artists

By Norman Kolpas

The entrance to the Booth Western Art Museum features a sculpture titled Attitude Adjustment by Austin Barton.

This story was featured in the October 2018 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art October 2018 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

“What you want to do is … materialize the spirit of a thing.” So said Frederic Remington in 1903, describing his approach to capturing the true essence of the Old West through his art. In similar fashion, the Booth Western Art Museum materializes the spirit of the West through its sterling collection of artworks, most of which were created by present-day artists. This remarkable museum is barely 16 years old and located in the town of Cartersville, GA, 45 minutes northwest of downtown Atlanta—and, fittingly, it is now in the midst of presenting a must-see exhibition of works by Remington.

The museum began as one man’s personal interest, which grew into a passion and then expanded into a grand and fully realized vision. Back in the late 1970s, a successful Cartersville entrepreneur—who has always remained anonymous—started exploring his budding interest in art by purchasing limited-edition prints, including some by Frank McCarthy, at a shop in a local mall. That’s where he struck up a conversation one evening with another collector who asked him, in passing, if he had been reading Southwest Art, then a relatively new magazine with a growing following.

Through the guidance of the magazine and other sources, the man and his wife embarked on their self-education. They visited galleries, attended shows like the annual Cowboy Artists of America exhibitions, and met artists. Gradually, they became part of the western art scene, amassing a significant personal collection over the next two decades.

That’s where Seth Hopkins, the museum’s executive director, enters the story. In 1999, he was working in a top management position for the collector’s company. “One day,” says Hopkins, “he came to me and said, ‘We’re selling this company. We’re going to build an art museum. And you’re going to run it.’” Between that moment and the opening some four years later, Hopkins did a deep dive into the world of western art—its history, the museum world, and the contemporary scene—which included “going to lots of shows and artists’ studios and reading Southwest Art.”

The Booth Museum, which opened in 2003, was named for Sam Booth, a friend of the founder; it was established in Cartersville, says Hopkins, “to honor and give back to the community where he made his money.” Its original 80,000 square feet of space was expanded to 120,000 square feet in 2009. That makes the Booth the largest permanent exhibition space for western art in the

United States.

And that fact often leads to two related questions. What makes Georgia a good home for an art museum dedicated to the West? And, aren’t there larger museums of western art actually located in the West? Hopkins offers ready, well-reasoned replies.

First of all, Georgia holds deep historic ties to the American West. “Anyone who did anything important in the West wasn’t necessarily born in the West,” says Hopkins, noting several key Georgia natives: John C. Fremont, an explorer, Civil War general, and politician; Doc Holliday, the dentist, gambler, gunfighter, and friend of Wyatt Earp; and Henry O. Flipper, a former slave who became the first non-white officer to lead the all-black Army “buffalo soldiers” in the Indian Wars.

“After the devastation of the Civil War,” Hopkins says, “many Southerners both black and white played a part in the great settling of the West.” To this day, he adds, “the core of the South and the core of the West are really made for each other. There’s a rodeo somewhere in Georgia every weekend. Horse culture, the cowboy mystique, and a love of western movies and TV are very strong. So a lot of people here come to the Booth to get their western fix.”

As for museums whose size may rival the Booth’s, Hopkins draws a key distinction. “We’re about a similar-size building to the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, for example. But it, like the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody or the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, are—first and foremost—history museums. Yes, they’re incredible art museums, too, but a lot of their square footage is taken up by historical exhibits.” By contrast, almost half of the Booth’s total square footage is dedicated to showing art, while the rest is given over to public areas, offices, and other essential functions. And of that exhibition space, the majority is dedicated to western art. (The remainder houses the benefactor’s collections of Civil War art and signed letters from every U.S. President.) That means, says Hopkins, “we have two or three times as much space where western art is being shown than other museums.”

And what a superb collection it is, with some 1,000 artworks among the Booth’s permanent holdings. Though the focus is primarily on contemporary western artists, some two dozen historic works provide impressive context. For example, there’s DANGEROUS TRAIL by W.R. Leigh, a 60-by-40-inch scene of a cowboy and his team of pack animals picking their way down a precipitous rocky path. And RED BUTTE WITH MOUNTAIN MEN, an awe-inspiring, 18-foot-long mural created in 1935 by the great Maynard Dixon, depicts Kit Carson leading a party of frontiersmen across a vast Utah landscape. “It’s worth traveling across the country just to see that painting,” says Hopkins.

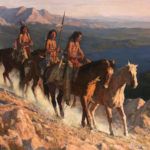

Among the many works by today’s top artists, highlights include four paintings by Howard Terpning: two oils, a gouache, and an acrylic-and-charcoal piece. “He is the undisputed king of living artists, the rising tide that has lifted the boat of western art,” says Hopkins. “To see his mastery of three different media is just incredible, and we’re very thankful to have those works.”

That sense of appreciation extends throughout the collection, which continues to grow at the rate of “one or two significant western artworks a month,” says Hopkins. Visitors can see a wide range of outlooks on the West, from the geometric landscapes of Ed Mell to the exuberant scenes of Kim Wiggins, the rollicking modern cowgirls of Donna Howell-Sickles to the witty Pop art interpretations of cowboys and Indians by Billy Schenck. Collectively, such selections deliver a powerful message that it’s perfectly possible to “express your feelings about western subjects in different ways,” Hopkins adds.

The Booth also embraces the works of great American Indian artists. Widely recognized names include the late Fritz Scholder, whose expressionistic depictions of tribal figures won him worldwide acclaim; the late Apache sculptor and painter Allan Houser; and the respected Crow painter Kevin Red Star. Such works represent one among many facets of the museum’s kaleidoscopic western vision. “It’s the subject that determines western art,” Hopkins sums up, “not who made it.” This approach adds up to an ever-expanding contemporary collection with real staying power.

And that makes the Booth an ideal setting for the special exhibition Treasures from the Frederic Remington Art Museum & Beyond, which opened on September 9 and continues through January 13. The show brings together more than 60 original Remington oil paintings, watercolors, illustrations, and sculptures, making it the most significant gathering of his works ever presented in the region. Highlights include three versions of his famed bronze THE BRONCHO BUSTER—one an original sandcasting, one a lost-wax copy, and the third a present-day reproduction of the sort sold through discount stores. “If you look at a cast done in Remington’s lifetime,” says Hopkins, “you can see the knuckles and veins on the rider’s hands. But on one of those cheap knockoffs, his hand looks like a melted chocolate bar.”

On a more emotional level, the show is likely to move visitors with a recreation of Remington’s Connecticut studio on December 26, 1908, the day he died following an emergency appendectomy at the young age of 48. The studio includes four artifacts on loan from the Buffalo Bill Center in Cody, including what is believed to be the artist’s last painting, THE CIGARETTE, a moody nocturne of four cowhands ending their day with a smoke around a campfire. “To be able to stand in that setting and look at his last painting will be a powerful moment for people,” says Hopkins.

“We know the show is going to be a blockbuster,” he adds. “And the opportunity to show Remington’s work in juxtaposition with all these great contemporary artists, so our visitors can understand the shoulders today’s artists are standing on and the traditions of western art that are still with us today, is an unparalleled experience.” It’s also a strong statement about how powerfully the spirit of the West lives on at the Booth Museum.

- Outside the Modern West Gallery, where Origami Pony by Kevin Box and Te-Jui Fu is on view.

- Frederic Remington, Life in the Cattle Country—Driving the “Round Up,” ca. 1901, oil, 27 x 40.

- Trail Along the Backbone by Howard Terpning.

- The Faces Gallery.

- The Modern West Gallery includes When They Ran With Freedom by Benjamin Nelson.

This story was featured in the October 2018 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art October 2018 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook