Meet 10 painters working in watercolors, acrylics & more

This story was featured in the March 2017 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art March 2017 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

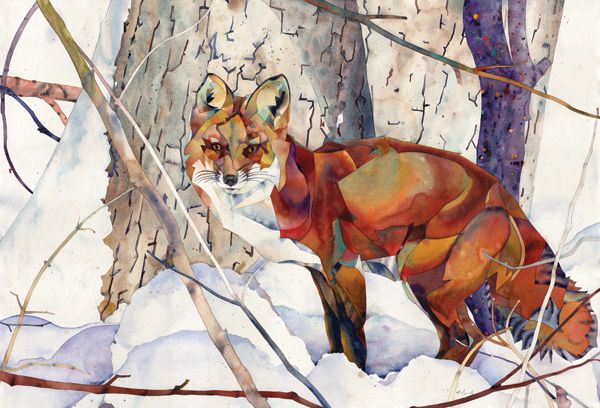

Travis Bruce Black

Travis Bruce Black, Secretly, watercolor, 31 x 45.

Although they may appear to be meticulously planned and controlled, Travis Bruce Black’s paintings of animals are much more spontaneous and magical. “I like that sense of watercolor where you don’t totally control it,” Black says. “You set up situations where you can 70-percent predict what will happen. But I’m not the type of artist that has a complete vision of what it will be; the exciting part for me is just putting a piece together and seeing where it goes.”

Black began drawing and painting in grade school but was often discouraged from pursuing a career in art. However, in his early 20s he was exposed to Japanese artist Yoshitaka Amano’s figural works. “That pillowy sense of color moving over a surface and giving a magical feel to the image” inspired him to return to art, Black says. He began to study with noted watercolor artists to develop his unique, kaleidoscopic style. He hopes to accomplish more than a simple reference with his work. “I’m taking the information I see and translating it into the language of the heart,” Black says. “I want to create something in the person that is viewing the piece, through color and abstraction.” Black describes his work as “drawing the shoe around the foot,” each piece coming together to portray a deep emotion lying beneath the image. In addition to painting, Black also works with the Gauri & Nainika fashion line, which creates dresses emblazoned with his work.

Black’s work can be seen at Canyon Road Contemporary, Santa Fe, NM; Providence Gallery, Charlotte, NC; and www.travisbruceblack.com. —Mackenzie McCreary

Joseph Alleman

Joseph Alleman, Urban Peaks, watercolor, 24 x 22.

The landscapes of Utah’s Cache Valley influence Joseph Alleman to see more than just the local scenery. “I’m not interested in going out and capturing landmarks,” Alleman says of scouting locations for his work. “I look for the mood of the scene when I visit a new place.” His motive lies in understanding his surroundings on a deeper level as he finds his inspiration in the changing regions, towns, and people that make Utah unique.

In looking at his oeuvre, it’s obvious Alleman has spent the better part of his life with a paintbrush in hand. His work with watercolor started when he was in high school, but Alleman now splits his time between oil and watercolor painting. Although he’s not a traditionalist in the sense of following a strict painting process at the start of a blank canvas, he does consider himself a “contemporary traditionalist.” Alleman admits to taking a bit of artistic liberty with his landscapes, as he paints on location and from reference photos equally, sometimes combining multiple scenes on a single canvas.

“The best part of Utah is that the seasons constantly change the same scene,” Alleman says. “It’s possible for the same field to look different every month of the year.” He looks forward to a fresh snowfall or spring snowmelt—anything to put a new face on a familiar landscape-—for inspiration.

See Alleman’s work at Astoria Fine Art, Jackson, WY; Mockingbird Gallery, Bend, OR; and Montgomery-Lee Fine Art, Park City, UT. —Katie Askew

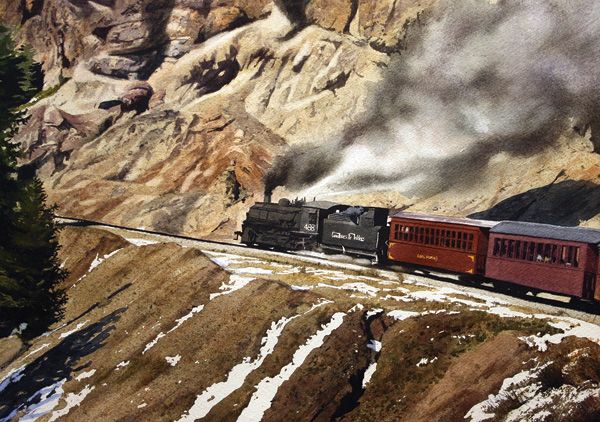

Robert Highsmith

Robert Highsmith, Making the Grade, watercolor, 14 x 20.

Robert Highsmith has been a dedicated painter for decades. In fact, he still works with the same brush he bought over 40 years ago, when his teacher told him to “go get a good brush.” Highsmith attended art school in Sarasota, FL, under several teachers who encouraged plein-air work. He remembers one teacher who was a “hard-edge, abstract watercolor painter,” with whom he credits his knowledge of papers, pigments, and techniques. Highsmith was also inspired by works of notable watercolor artists such as Andrew Wyeth. “The first few years I was painting, I saw a book about Wyeth, and I realized what some people could do with watercolors,” he says. “I strive do what they do because I knew it could be done.”

Over the years, Highsmith has lived all around the United States, which has brought a variety of subject matter to his work. When he lived in Connecticut, he painted rock walls and cows and barns; when he lived in South Carolina, he painted marshes. But his heart lies in his childhood home of Las Cruces, NM, in the heart of what he calls “John Wayne country.” “I’ve always felt that this is where my heart is: in the desert Southwest with the cactus in the canyon and the cowboy scenes.” The artist continues to return to places like Moab, Monument Valley, and Canyon de Chelley. With his work, Highsmith is trying to transport viewers while also giving them the feeling of “going back to your roots.”

Highsmith’s work can be seen at Manitou Galleries, Santa Fe, NM; The Cutter Gallery, Las Cruces, NM; Four Corners Gallery, Bluffton, SC; and www.rhighsmith.com. —Mackenzie McCreary

Mary Alayne Thomas

Mary Alayne Thomas, Whispers, watercolor/encaustic, 14 x 14.

Painter Mary Alayne Thomas uses her vivid imagination, cultivated in her childhood, to inform her whimsical watercolor- and-encaustic paintings of nature. Thomas grew up under the influence of a ceramic-artist father and a textile-artist mother who encouraged her creative endeavors by taking her along to art fairs and enrolling her in watercolor lessons. “I fell in love immediately, thrilled to find a means of expressing the ideas that had begun to germinate in my imagination,” Thomas says. “Its versatility suits any style I attempt, and it feels entirely natural to me.”

Thomas says she was largely influenced by mystical stories about adventures in other worlds, specifically a collection of books titled My Bookhouse. The feeling of being transported through both story and nature remains the underlying theme in her work. Thomas describes her work as modern and uses the combination of watercolors and encaustic to create “an instant atmosphere, a three-dimensional painting.” She is increasingly aware of the need to preserve the environment, as well as human connection, which she is attempting to show more in her work. “I hope to express the importance of connecting with one another to preserve the wildness in nature and ourselves,” Thomas says.

Thomas’ work can be seen at Giacobbe-Fritz Fine Art, Santa Fe, NM; Lark & Key Gallery, Charlotte, NC; Lotton Gallery, Chicago, IL; and www.maryalaynethomas.com. —Mackenzie McCreary

Carolyn Lord

Carolyn Lord, Garden Afternoon, watercolor, 20 x 20.

From landscapes to architecture to garden scenes, a wide variety of subject matter appeals to Carolyn Lord. “I see other artists’ work, and they are painting the exact same thing all the time, and I wonder how they can be so boring,” Lord says. “I have lots of interests, and I’m always changing and trying different things.” While she painted exclusively in watercolors for many years, the artist has been experimenting more with oil and other subjects. Lord’s work borders on abstraction as she continues to focus her efforts on developing a sensitivity to shapes and silhouettes. She also is working to tone down her use of bright colors, especially in her larger paintings.

For Lord, living and painting in suburban Livermore, CA, can be challenging, but she continues to find endless inspiration in her garden. “I feel I can find and create beauty wherever I am,” she says. This is one of the reasons the artist gravitates toward watercolors, which are easy to transport when she goes on painting excursions. Lord says she normally works entirely from life, although she may begin to work from photos as well. Although she has been told predictability is the key to success for a career in art, she cannot deny her curiosity. “I remember hearing that you’ll be successful when you continue to do exactly what galleries expect you to do,” she says. “But I can’t do that. I like to surprise people.”

Lord’s work can be seen at Calabi Gallery, Santa Rosa, CA; California Watercolor Gallery, Fallbrook, CA; Nancy Dodds Gallery, Carmel, CA; Oh-Be-Joyful Gallery, Crested Butte, CO; Signature Gallery at Studios on the Park, Paso Robles, CA; Thunderbird Foundation, Mount Carmel, UT; and www.carolynlord.com. —Mackenzie McCreary

William Haskell

William Haskell, Abiquiu Hacienda, acrylic, 12 x 16.

William Haskell’s parents recognized an inherent artistic gift in their son when he was only 4 years old. He went on to capitalize on their support and, with his sights set on becoming a wildlife artist, started taking painting classes and apprenticed with a wildlife artist in Wisconsin for a year when he was a teenager. After realizing how meticulous wildlife art could be, he studied graphic design at the University of Wisconsin-Stout instead. “Growing up in the Midwest, you’re not led to believe that making a living as an artist is even possible,” Haskell says. After a career as a professional illustrator, Haskell eventually moved to New Mexico with his wife in 2002 to pursue art full-time.

He first became infatuated with the dry-brush watercolor technique for its texture and richness, but today, he mostly focuses on acrylics as a natural extension of his work in landscapes. His deeply rich colors and exaggerated shapes imbue his landscapes with a surrealistic quality, though Haskell says he sees his work as a combination of realism and modernism. “I want to cross boundaries here,” he says. “I think work can have a modern quality to it but appeal to people who understand traditional art.”

Ultimately, Haskell subscribes to his own kind of art movement, opening himself up to all kinds of different artistic influences and eras from the past. “I just want people to know my art from across the room,” he says.

See Haskell’s work at Manitou Galleries, Santa Fe, NM; K. Newby Gallery, Tubac, Arizona; and Lovetts Gallery, Tulsa, AZ. —Katie Askew

Marlin Rotach

Marlin Rotach, Cowboy, watercolor, 23 x 17.

Missouri painter Marlin Rotach grew up as a sickly child, but he soon found this didn’t hold him back from a promising future in art. Rotach would help paint backgrounds on billboards for cattle farms and horse ranches with his father, who always supported his ambitions. However, after attending art school and working in acrylics for several years, he developed an interest in scuba diving. Rotach traveled to places like Hawaii and the Cook Islands, where his love of painting the local flora blossomed. “I was in a parking lot on the Big Island in Hawaii, and I looked up and saw these big, beautiful flowers blooming,” Rotach says. “I just had to paint them.”

The artist adopted techniques used by masters such as Caravaggio to give his subjects more intensity. He says, “For me, everything is light—that’s where watercolor has an advantage because it depends on the reflection of light.” Working mainly in his studio from photos, he uses dramatic lighting in his pieces to simultaneously simplify the subject and exaggerate the mood or emotion he is trying to portray. This approach has become particularly important as he continues to turn his attention toward the western subject matter of his childhood, especially horses.

Rotach says his excitement about his work has never faltered. “I’m excited about what I’m working on but also about facing that new sheet of blank, white paper,” the artist says. “It’s truly like magic, how these things form.”

Rotach’s work can be seen at American Legacy Gallery, Kansas City, MO; Sorrel Sky Gallery, Santa Fe, NM; and www.marlinrotach.com. —Mackenzie McCreary

Rance Jones

Rance Jones, Gladiolas, watercolor, 21 x 18.

When Rance Jones was in high school, flipping through issues of Southwest Art magazine, he felt a deep connection to Gordon Snidow’s representational compositions found in the pages. “The magazine played a significant role in me learning how to paint,” Jones says. He went on to study graphic design at the University of North Texas—an education that taught him the compositional values and strong use of light so important in his paintings today. He later took a watercolor workshop that completely focused his life’s work on the medium.

Jones identifies most with the tangibility of photo-realism in his watercolor paintings. “It’s hard to hold someone’s attention for more than split second today,” Jones says. “But photo-realism gives me the opportunity to engage with the viewer more and make them look deeper at the painting.”

For Jones, art is less about the outcome and more about being involved in the journey of painting. Part of that experience involves him seeking out indigenous cultures around the world and capturing the unspoken reverence within those communities—he recently returned from a trip to Peru. “It’s kind of my protest against the rush toward progress at any cost,” Jones says. He hopes to preserve and chronicle the beauty in these endangered cultures. “When there’s not a recognition of the destruction, cultures can be erased in a blink of an eye,” he says.

See Jones’ work at Worrell Gallery, Santa Fe, NM; Quantum Contemporary Art, London; and www.rancejonesart.com. —Katie Askew

John Fawcett

John Fawcett, Crossing Willow Creek, watercolor, 16 x 26.

As a veterinarian for 20 years, John Fawcett’s life has always been filled with animals. But it wasn’t until 1991 that Fawcett visited a western art show and, awestruck by the work around him, dedicated part of his life to perfecting his art. Just five years later, after exhibiting his work at an invitational art show and gaining representation at a gallery, Fawcett sold his veterinary practice and became an artist full time. Today, Fawcett, his wife, and their dogs and horses split time between a ranch in the mountains of Colorado and a farm in Pennsylvania.

Fawcett, who is completely self-taught, fell in love with the spontaneity of watercolor before ever working with oils. “The fluidity and happy accidents associated with watercolor make it the perfect medium,” Fawcett says. “There’s always a new technique, brush stroke, or composition to learn.” With his veterinary background, Fawcett also hosts horse-painting workshops to offer insight on the anatomical structure of horses—hoping to give back in the same way he first learned artistic techniques. But his art isn’t only focused on animals; he also seeks to subtly tell a story through historical imagery of Native Americans, cowboys, and pioneers.

Fawcett finds his success within the viewer. “If you can evoke some kind of emotion or connect with the viewer in any way, then you’re successful as an artist,” he says.

See Fawcett’s work at InSight Gallery, Fredericksburg, TX; Settlers West Galleries, Tucson, AZ; Legacy Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ, Jackson, WY, and Bozeman, MT; and www.johnfawcettstudio.com. —Katie Askew

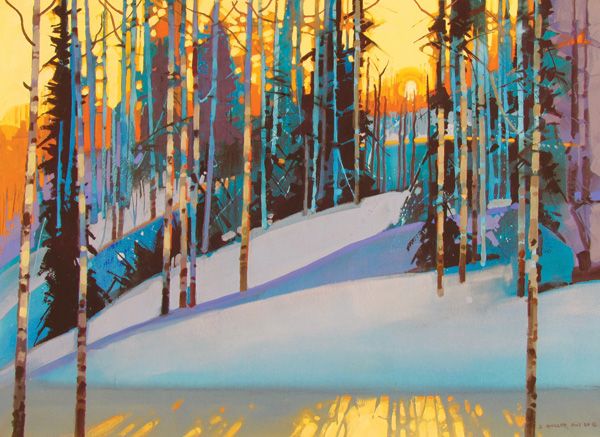

Stephen Quiller

Stephen Quiller, Flickering Late Light Along the Ridge Trail, water media, 22 x 30.

Although watermedia artist Stephen Quiller got his start during the peak of abstract expressionism, he was drawn toward a more representational approach featuring the mountainous environment near his home in Fort Collins, CO. Quiller attended Colorado State University, where he majored in art and art education. There he learned about oils, acrylics, ceramics, and printmaking. However, his main focus remained on watercolors, and professors encouraged him to embrace the abstract techniques of the time. “I was uncomfortable with it, but it was important because it helped me to not think quite so literally and think more abstractly, despite my representational technique,” Quiller says.

Today the artist lives in the high mountains of Colorado near the headwaters of the Rio Grande, where he paints cliffs, aspen patterns, and snow shadows. “They are things that I have become a part of during the 45 years I have lived here,” he says. During the summer, Quiller works mostly en plein air and finishes the final 20 percent of each painting in his studio. But during the winter, he works in the studio from photos he has taken during daily cross-country ski trips. He says the seasonal differences in his process end up complementing each other. “When I’m outside, there’s an energy and a communion that you get when working directly from nature,” Quiller says. “When I’m in the studio, I’m much more interested in composition and color and design—the visual qualities of the watermedia.”

Quiller’s work can be seen at Mission Gallery, Taos, NM; Quiller Gallery, Creede, CO; and www.quillergallery.com. —Mackenzie McCreary

This story was featured in the March 2017 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art March 2017 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook