Meet 12 sculptors who work in a variety of materials

This story was featured in the July 2017 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art July 2017 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

Pokey Park

Pokey Park, Brown Pelican, bronze (relief), 28 x 19 x 11.

In the animal and wildlife kingdom, there are very few creatures, if any, Pokey Park wouldn’t sculpt. Among her oeuvre of stylized bronzes are whimsical representations of the loggerhead sea turtle, birds, otters, bears, and the desert bighorn ram. By portraying the personalities of various animals, from endangered species to domestic critters, Park seeks to convey analogous human traits, as well as the universal myths that different cultures attach to symbolic animals like the fox or rabbit. “I realized that everyone’s stories solve similar questions,” she says. “When I do an animal sculpture, such as a tortoise, those myths come out. I want to show the connection rather than the differences between people.”

The nature lover prefers to observe her wildlife subjects in their native habitats, whether it’s near her homes in Arizona and Colorado or in far-flung countries like Mongolia. “My camera is my right arm,” says Park. “Google is a wonderful resource, but there’s nothing like seeing the personality of animals come out in their natural setting.”

See Park’s work at Slate Gray Gallery, Telluride, CO; Broadmoor Galleries, Colorado Springs, CO; K. Newby Gallery & Sculpture Garden, Tubac, AZ; Mark White Fine Art, Santa Fe, NM; SmithKlein Gallery, Boulder, CO; and Fredericksburg Good Art Company, Fredericksburg, TX. —Kim Agricola

David Unger

David Unger, Fragrance of Spring, bronze, 16 x 9 x 12.

Over the 50 years he has been sculpting, David Unger has experimented with chisels, wire, wood, and welding, but nothing quite compares to the joy he feels when sinking his fingers into a soft slab of clay. In Unger’s hands, the malleable lumps of earth become an extension of his emotions. “With clay you can put more of yourself in the piece,” says the figurative sculptor. “I can feel the figures taking shape, and I feel more of a passion for what I’m creating.”

Many of his resulting tabletop bronzes depict interactions between a man and a woman through the supple movements of a dance or embrace. Unger takes liberties with the human form, he says, by blending soft curves, sharp angles, and smooth planes into partly abstract, partly realistic portrayals. “A lot of people are afraid to touch art, but with sculpture you’re supposed to touch it,” he insists. “People should run their hands over it. Hopefully, when they do that, they can feel my emotions coming off my sculpture and feel what it says.”

Performances at the nearby University of Arizona School of Dance provide a steady stream of inspiration for the Tucson, AZ, artist, but he tends to harvest ideas everywhere he goes. “Wherever there are people, there are new sculptures,” he says. Which is why Unger casts just 12 bronzes of each piece, then destroys the mold. “I have so many ideas bubbling around in my head,” he says. “I can’t wait to get to my studio every day.”

Find Unger’s work at Mary Martin Gallery of Fine Art, Charleston, SC, and Naples, FL; and Scott Bundy Galleries, Kennebunkport, ME. —Kim Agricola

Raymond Gibby

Raymond Gibby, Choose Your Friends Wisely, bronze, 17 x 13 x 11.

The biggest source of inspiration for bronze sculptor Raymond Gibby is his kids. The artist uses the everyday activities of his seven children as fuel for his narrative wildlife sculptures. “I am interested in using animals to convey stories and messages about humanity,” Gibby says. “I use animals because they tend to be very truthful according to their instincts and their behaviors, just as young children can be.”

Gibby originally studied illustration but found his calling in sculpture. He eventually opened his own foundry in Arkansas and earned gallery representation. Unfortunately, two years later the foundry was destroyed in a fire, leaving the artist with no molds. Since then, Gibby has moved to Utah to work with Baer Bronze, the foundry where he apprenticed during college.

The artist has always been interested in animals, but seeing his kids interact with nature adds another layer to each piece. ROOM FOR ONE MORE, for example, shows a grizzly bear forcing his way to a waterfall to catch fish, knocking others into the water. “The same thing happens in our house when I yell, ‘Ice cream,’” Gibby laughs. The artist also considers the sculptures as visual lessons for his kids. He says the piece CHOOSE YOUR FRIENDS WISELY is a sort of cautionary tale for his four daughters. “I’m not content with just sculpting an animal,” he says. “I’m always thinking about the kids as well.” Gibby’s work can be seen at The Signature Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ, and Santa Fe, NM; Mountain Trails Gallery Sedona, Sedona, AZ; Mountain Trails Gallery, Jackson, WY, and Park City, UT; and www.gibbybronze.com. —Mackenzie McCreary

Kim Obrzut

Kim Obrzut, Morning Song, bronze, 29 x 11 x 11.

Kim Obrzut knew she would dedicate her career to sculpture after just five minutes in a bronze-casting class at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff. “I fell in love with it, all of it, and in every way,” she remembers. “It was fate.”

Today, Obrzut equates her original greatest inspiration with her grandfather: watching him carve kachina dolls from cottonwood root while singing and praying sparked the creative spirit in her. After his death, she realized that her inspirations also come from everyday life and the “insane genius of nature, the primal instinct of everyday simplicity, and the innate beauty of mankind.” Fellow Native American artists, who helped her develop her creativity, have also mentored her along the way.

Her Hopi maiden sculptures and other fine bronze works reflect the Native American culture and contemporary elements of life. Since Hopi history is not written down, Obrzut finds joy in meeting people who share the rich oral history of her culture. See more of Obrzut’s work at Exposures International Gallery, Sedona, AZ; The Signature Gallery, Santa Fe, NM; Mountain Trails Gallery, Jackson, WY, and Park City, UT; Santa Fe Indian Market, Santa Fe, NM; and www.kimobrzut.com. —Katie Askew

Victor Issa

Victor Issa, First Catch, bronze, 61 x 21 x 18.

Victor Issa says he’ll need two lifetimes to finish all the sculpture ideas that inspire him. “I work with the human form because I find it to be the most expressive,” Issa says. “It can capture and portray emotions like no other subject matter.”

As an art student at the University of Nebraska and later at Union College, Issa dabbled in oils, watercolors, and sculpture. But eight years after graduating, he became enamored with the flexibility in both the composition and color of sculptures and dedicated his time to the craft. He moved from Lincoln, NE, to Loveland, CO, after one of his mentors, sculptor George Lundeen, said to Issa, “If you’re serious about sculpture, you’ll live in Loveland.” Now, Issa is thankful for the community of sculptors and resources available to them in the area.

Today, his bronze figurative work is a mix of commissions, models, and imagery of other people that inspire Issa in life. “I want to focus on what uplifts the soul and what brings us joy,” he says. “I pursue the revealing and elevating of our hearts through my work.” You can see more of Issa’s bronze sculptures online at www.victorissa.com. —Katie Askew

Chris Turri

Chris Turri, Lightning Shaman, patina on metals, 64 x 15 x 3.

Chris Turri’s sculpture is an ode to simpler times. He misses the days when kids could run around outside without cell phones constantly ringing, when communities had identities instead of big-box stores. Turri’s works incorporate elements of Native American culture and utilize universal symbols to weave a tapestry of history, community, and keeping stories alive. “I think that people are wasting away their time by not being creative and not turning electronics off,” Turri says. “You have to look inside and find out what makes you tick and makes you shine in order to thrive.”

Turri, who moved to Corrales, NM, three years ago, uses reclaimed steel and copper to make his art. “I love working with metal,” he says. “It changes with the seasons, gets better with time, and is permanent.” He’ll often work with the skins from vehicles made in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, finding rich color and character buried in salvage yards. He also developed his own patinas and a special rusting container, which speeds up the process and adds a distinctive touch to his large-scale sculptures.

“I’m blessed to be able to do my craft full time in New Mexico,” Turri says. “We have a secret in this state: It’s the mountains, desert, rivers, and positive energy. It’s a beautiful place to create.” You can find Turri’s sculptures at Waxlander Gallery, Santa Fe, NM; Rogoway Turquoise Tortoise Gallery, Tubac, AZ; Metallo Gallery, Madrid, NM; Off the Beaten Path, Cloudcroft, NM; and www.christurriart.com. —Katie Askew

Bob Boomer

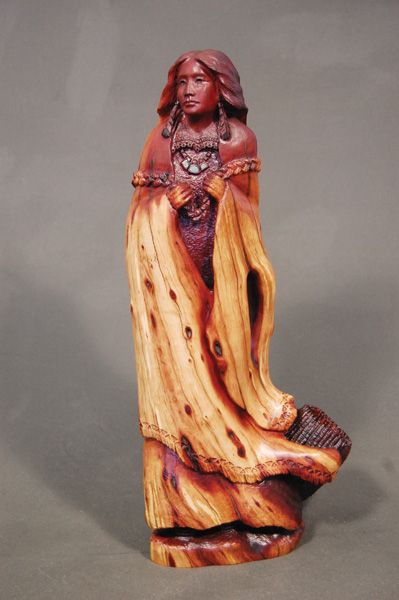

Bob Boomer, Young Mother, manzanita, h19.

“I have always been drawn to wood,” says California sculptor Bob Boomer. His affinity for the medium emerged in elementary school, when his sixth-grade class studied Native Americans. “After we finished our work, we were allowed to sit in the back of the room and carve,” he says. “I remember not wanting to put it down.” More than 60 years later, the artist continues to be intrigued with how wood responds in his hands.

In the forest surrounding his Sierra Nevada home, Boomer finds ample material for his art. He favors the hard, colorful wood of the shrubby manzanita. The tree’s medicinal and culinary importance to California’s Native Americans ties into the spirit of his work and the female Indian figure he reveals in each piece. “I go out and look for old, downed manzanita. It’s dried and cured, and I know where the defects are going to be,” he explains.

He’s fascinated by both the color and the inherent twist of the wood. “The center is always darker. The outside is where you get the light colors. I play with that,” Boomer says. Working with the grain and with each piece’s unique knots and color, he rough-cuts a brow line, mouth, and nose. “Then the piece begins to take on a life. You see a posture, even an expression,” he says. From there he listens to the wood, adding, “Nature does a lot for me. I just add my spirit, my vision.”

Boomer’s work can be found at Mockingbird Gallery, Bend, OR; Mainview Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ; and www.bobboomerstudio.com. —Laura Rintala

T Barny

T Barny, Veraison—Ripening, marble, 26 x 19 x 12.

When asked to describe his artistic style, California stone sculptor T Barny sidesteps art-world terminology, thoughtfully and emphatically responding, “Touchable.” For Barny, sculpture is a medium of conduction in a world where physical touch is too often reduced to tapping on digital screens. “I put a bearing or a pin in each piece, so you can turn it,” Barny says. From every angle, you get a different negative space, but, more importantly, “I’m getting you to touch the sculpture.” Indeed, he says that people who cannot see with their eyes grasp his work most immediately. His abstracted shapes feature loops and ribbons of polished stone loosely knotted around itself. Running their hands over the smooth, “soft” surface, the blind quickly discover its secret—a design element Barny employs in almost every piece: a single, Möbius-strip-like edge, which, for the artist, represents the circle of life and the infinite contained in the finite.

The artist begins with rough-cut stone and allows the stone itself to guide its shape. “You discover more things by direct carving than by trying to fit a preconceived shape into a block,” he says. “I make carved stone seem soft and magical. When people see it and touch it, they get a part of that magic. I’m bringing something that is millions of years old, formed in the crust of the earth, and giving it life.”

Barny’s work can be found at Corrick’s, Santa Rosa, CA; Hunter Kirkland Contemporary, Santa Fe, NM; Melissa Morgan Fine Art, Palm Desert, CA; Aerena Galleries, St. Helena, CA; Kelsey Michaels Fine Art, Laguna Beach, CA; and www.stonewizard.rocks. —Laura Rintala

Paige Bradley

Paige Bradley, Freedom Bound, bronze, 46 x 64 x 42.

Paige Bradley’s strong, lyrical figures represent the artist’s desire to empathize with her fellow human beings. “I feel like my work is a bridge to humanity,” she says. Inspired by the movements of both yoga and dance, the artist renders her figures in bold textures as they sit, stand, bend, or hang. “Texture is the handprint and how the piece is brought together, and when that goes away it’s harder to feel the humanity behind it,” Bradley says. “Anything can look shiny and polished, but it’s much harder to know when to stop and trust yourself that the piece has life and energy as it is now.” Through this transparency of process, the artist strives for a deeper purpose of connecting to a viewer through their soul, rather than simply recording a personal story. “I want to make people see that we’re all made from the same things and we have more in common than we have different,” Bradley says. “I want to fight that fear and isolation we have today and make people feel they’ve been understood and connected with another person.”

Bradley’s work can be seen at Classic Art Gallery, Carmel, CA; Canyon Fine Art, Santa Fe, NM; Thornwood Gallery, Houston, TX; Windsor Fine Art, New Orleans, LA; and www.paigebradley.com. —Mackenzie McCreary

Jill Shwaiko

JIll Shwaiko, Row 1: Laughing Family Member, bronze, h6. Mini on a Mission, bronze, h4. Row 2: Releasing the Birds, bronze, h13. Raising Up, bronze, h13. Row 3: Releasing the Birds, bronze, h18.

When she first began pursuing art, painter and sculptor Jill Shwaiko wasn’t focused on sheep. But when her interests led her to primitive cultures and the rock-art petroglyphs of the Southwest, she found a spiritual connection with the animals. “I wanted to create this primal, emotional, spiritual, and visual experience,” Shwaiko says. “The sheep just kept taking over and having their own voice in the matter.”

Shwaiko’s simplified, primitive bronze sculptures depict differently shaped sheep on various adventures. Whether they are hoisting birds into the sky or sitting and gazing at the stars, they seem to convey their personalities through simple mannerisms. “Somewhere in our core we have memories of these primitive shapes, and they express things to us,” Shwaiko says. “The horns add so much to express a number of things such as consternation, surprise, and pride.” The sheep also facilitate a deeper connection between the artist and the viewer. “People like to create their own sets of sheep because they see personalities from their family,” she says. “Then there’s this joint effort between the clients and myself in the creative process.” Shwaiko’s work can be seen at Indigo Gallery, Madrid, NM; Carole LaRoche Gallery, Santa Fe, NM; Mirada Fine Art Gallery, Indian Hills, CO; and River Trading Post, Scottsdale, AZ. —Mackenzie McCreary

Heather Johnson Beary

Heather Johnson Beary, Peregrine, bronze, 15 x 9 x 8.

Heather Johnson Beary chose bronze sculpture as her medium because three-dimensional works have no boundaries. “The possibilities are endless with bronze,” she says. “One can use the strength of the metal to bring the illusion of weightlessness to a very heavy work of art.” Beary enjoys creating works that have a tactile quality, allowing viewers to perhaps feel what she felt while making them.

In fact, she was recently commissioned by the Friends of the Library in Prescott, AZ, to create the interactive and tactile monument called LIBRARY LIZARD. The giant lizard, which is reading a book, is sitting at the entrance of the Downtown Prescott Public Library, and kids love to play on it. Beary has also created bronze work for famous art collectors like Jimmy Buffett, Matt Lauer, and Sir Richard Branson.

The Arizona-based artist feels inspired by the unspoiled, panoramic spaces of the Arizona desert and the movement, serenity, sun, and wind she finds there. “I think that nature and the simple, unencumbered gestures in life are so important to someone’s well-being,” Beary says. “The communion between humans and nature can be overlooked or even lost to our everyday responsibilities, obligations, and concerns.”

Her representational style is a form of language for Beary, as she feels fully understood through realistic bronze works instead of words. “I have the unique opportunity to express the way I see things in a language that is clear and hopefully moving,” she says. You can read more about LIBRARY LIZARD and see many of Beary’s other works at www.hjohnsonbronze.com. —Katie Askew

Josh Henrie

Josh Henrie, Guardian, basalt/olivine, 4 feet high.

Josh Henrie’s sculptures often mimic the rugged, jagged imperfections found in the Washington wilderness where he lives. The self-taught carver worked his way from softer stones up to harder ones like basalt and marble, later combining them in his sculptures. “I really learned the slow, painful way,” Henrie says. “I had to struggle with it and figure out where I wanted to go, what I like, and how the rock speaks to me.”

While Henrie’s specialties lie in his depictions of animals, he also works in portraiture. He follows the traditional realism of the Renaissance, while giving it a contemporary twist. The artist draws inspiration from passing observations of mannerisms, body types, fabric ripples, and more. “The hardest part is capturing what I see in everyday life,” Henrie says. “I like that whole organic quality. I want this to be reality with an understanding of the world as it is now.”

However, while the artist may have a plan for a sculpture, he says the materials determine much of the final product. “I’ll never force the stone to do something, so if I want to do a branch one way, but I see the stone going in a different direction, I’ll go with that granular texture to make it more branch-like,” Henrie says. “What I really want to do is bring out that beautiful quality of what makes that subject special.” Henrie’s work can be seen at White Bird Gallery, Cannon Beach, OR, and Matzke Fine Art, Camano Island, WA. —Mackenzie McCreary

This story was featured in the July 2017 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art July 2017 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook