By Rosemary Carstens

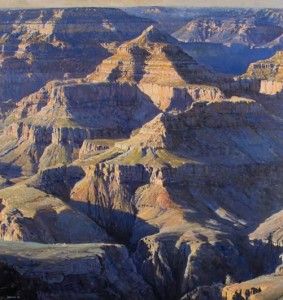

Theodore Roosevelt once said, “There are no words that can tell the hidden spirit of the wilderness, that can reveal its mystery, its melancholy, and its charm.” Peter Holbrook’s paintings prove this again and again. How do you describe the awe that a view of the Grand Canyon’s magnificent topography inspires? The peace that comes while gazing at unspoiled terrain, walking in a dry forest, or sitting on a rocky shoreline experiencing the crash of the ocean? Only through a camera’s lens or the hand of an artist can we relive those moments. Holbrook occupies that intersection, working in a realist style while incorporating painterly effects.

Ever since he was a young man, Holbrook has sought adventure and out-of-the-box solutions to what life brings his way. His bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth College was followed by a year and a half spent hitching around the world from Europe to the Middle East and then on to India (where he turned 21), finally landing more or less flat broke in Africa. From there he signed on as a merchant seaman on an American freighter heading back to the United States. Sharing tales of close calls and tricky situations, Holbrook says, “I had a major talent for getting along cheap and surviving on the street or the sea.”

Back in the United States, the artist attended the Brooklyn Museum Art School in New York as a Max Beckmann Fellow. Later he lived in Chicago, working at a variety of jobs—draftsman, carpenter, taxi driver—while beginning to exhibit his work professionally. In a period when the concept or gesture of a work of art took precedence over traditional aesthetic and material concerns, Holbrook continued his independent approach. Born in New York City and growing up in white-collar suburbia, his early influences were urban, including the late 19th-century Ash Can School of artists, whose lush style was put toward gritty ends in depicting the brutish realities of city life.

Yet Holbrook quickly realized that it was the landscape, not the urbanscape, that drew him. It was a time when portrayals of nature were deemed sentimental and thus devalued; but Holbrook—always a man to go his own way—knew he wanted to share the landscape’s beauty, to translate its grandeur to paintings that depicted reality as closely as possible, yet with a painterly flair.

Looking back over fifty years of work, the artist remarks, “I have always admired the great realists. There’s a basic visual magic in the ability of pigments to credibly translate our three-dimensional world to the flat, two-dimensional world of paper and canvas. A good painting allows us to momentarily enter another’s consciousness and implies dimensions beyond what is normally seen. It makes painting a spiritual exercise, requiring imagination to create credibility.”

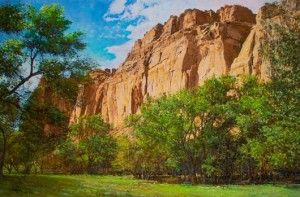

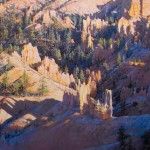

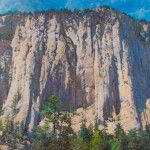

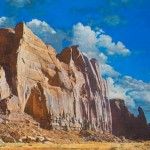

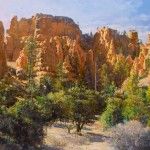

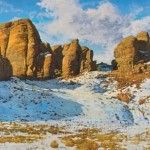

When it came to choosing his own subject matter, there was a lot to inspire the artist in his East Coast environment. “Everyone has a geographical ‘comfort zone,’ a familiar-feeling environment based on childhood experiences,” Holbrook says. “I grew up a forest dweller, surrounded by lush foliage, and I feel better living close to an ocean.” When he traveled west, however, he discovered his work’s true milieu: the stark, dry canyonlands and desert geography of the Southwest, as well as California’s rugged coastlines and high sierra. Among these vistas, which contrasted so sharply with those of his earlier years, Holbrook could see freshly. Nothing was assumed to be present; every new detail caught his eye. He continues to be captivated by the way the forces of nature impress themselves upon the land.

When not painting canyons, for which he’s well known, Holbrook often paints boats and coastal views. Decrepit fishing boats are always appealing. “I’m moved by the idea of going out in flimsy vehicles, gambling your life to make a living in a dying industry,” he says. “Since my days as a merchant seaman, the sea has seemed to me much like the canyons I love to paint. Beneath the level where you stand, there is a whole other world. Both the canyons and the sea represent vast mysteries.”

In 1970 Holbrook came to the redwood country of Northern California with $10,000 in his pocket, half of which he spent on the purchase of five completely unimproved acres. He camped first and then designed and constructed the family house where he and his wife, Pat Weaver, still live today.

In the following years he built a studio, wood shop, print shop, large garage, and rental house; he also reared two children and expanded his career while teaching art at California State University, East Bay. Holbrook’s large, light-filled studio lies downhill from the main house, toward a year-round creek, and is built into the hillside for better climate control. An unrepentant night owl, the artist spends 9 to 10 hours a day there, six days a week—reviewing hundreds of reference photos, consulting topographical maps, and thumbing through field material until inspiration hits. About six hours a day he’s at the easel, with music by jazz greats Dave Brubeck, Count Basie, Charlie Parker, and others playing softly in the background.

At 70 years old, the artist is one of those rare people who are living and working just where they’re meant to be. When asked about his happiest moment in his California enclave, Holbrook—who has always enjoyed sports and still plays competitive golf and tennis—smiles and says, “Fall of 1980, when my softball team won the local championship. I didn’t get to play, however, because I was busy assisting in the home delivery of my first child!”

Few adventurous pursuits deter Holbrook, who utilizes photography to collect reference material. He developed an interest in aerial photography and learned to fly a ParaPlane—essentially a motorized parachute with wheels—to gather bird’s-eye views of his favorite landscapes. He also enjoyed years of motorcycle touring and camping through Canada, Mexico, and the western United States. Everywhere he goes, the artist is attentive, noting how light, land, and water interact in myriad ways.

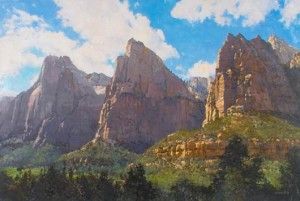

As can be seen in pieces like COURT OF THE PATRIARCHS, Holbrook has mastered the panoramic view. The viewer senses what it is to stand on the edge of the canyon, as though on the edge of time, taking in the color, the texture, and the immensity of the scene before him. The painting seems at first glance to be truly photorealistic, but a closer examination reveals Holbrook’s signature bursts of impressionistic strokes. This complex effect indicates the artist’s deep comprehension of light and shadow, flatness and texture, as well as how detailed components relate to one another. “Court of the Patriarchs,” Holbrook notes, “illustrates a strategy for managing excessive textural detail that might distract from the overall effect. I chose backlighting to simplify the large shapes and to eliminate all but a few highlights. I carefully shifted from tight focus to soft focus and included a controlled modulation of color from foreground yellows and oranges to background purples.”

Beth Lauterbach, owner of Scottsdale Fine Art, remarked recently about Holbrook’s painterly approach: “Up close his work is almost abstract, with each brushstroke artfully juxtaposed against the next, and with the proper color and value working in concert to create the photographic effect the viewer sees at a distance.”

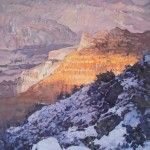

A variety of moods, created by weather and seasonal transformations, animates Holbrook’s work, but winter is a favorite time, especially for visiting national parks. “I try to plan my trips to catch a fresh snowfall on a relatively clear day,” he says. “As can be seen in my painting of Moran Point, snow eliminates excessive ground texture and provides a foil for the intense colors that make this place unique. Snow also assists in describing the land, defining horizontal surfaces, and setting up marvelous patterns of lights and darks.”

Holbrook’s paintings are not simply documentary, but represent his talent for conjuring nature’s remarkable variety and power. Bruce Cody, who represented the artist at Charlene Cody Gallery in Santa Fe for more than 11 years, observes that Holbrook has “a rare quality among realists, many of whom strive for extreme precision at the expense of personality. Peter is one of very few realists whose work shows genuine passion and is highly autographic. He pumps up a potentially photographic image to something far better.”

Holbrook has had more than 50 solo exhibitions and has executed major commissions for such entities as the Clorox Corporation and the General Services Administration. His work has been the subject of numerous catalogs and magazine and newspaper articles, as well as anthologies, and many major museum collections include his paintings.

Ultimately, Holbrook’s paintings are more than technically sound and visually appealing. They constitute a pictorial record of our wild places during a time when the natural environment is under fire and we have a deep need for reminders of our earth’s amazing grace.

Representation

Scottsdale Fine Art, Scottsdale, AZ; Bingham Gallery, Mt. Carmel, UT; www.peterholbrook.com.

Upcoming show

Solo show, St. George Art Museum, St. George, UT, June 11-September 10.

Featured in January 2011.