Mark Haworth aims for emotional resonance through his art

By Gussie Fauntleroy

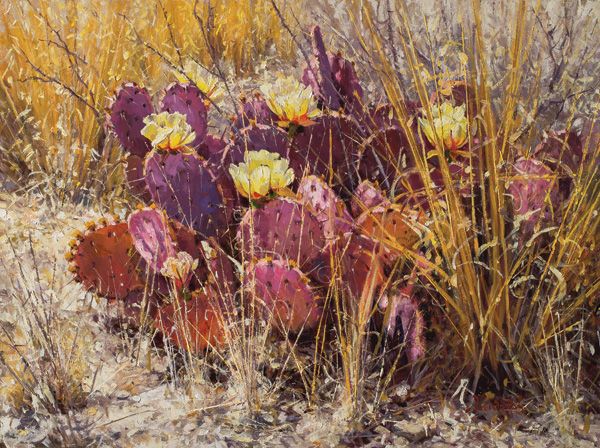

Mark Haworth, Red and Yellow Sticks a Fellow, oil, 12 x 16.

This story was featured in the February 2018 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art February 2018 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

Mark Haworth remembers the first time he looked at something and saw it “like an artist.” He was 7 years old. It was one of those first happy days of summer on the outskirts of Houston, and Haworth was settled onto the bank of a bayou in the midday sun. A red-winged blackbird landed on a cattail nearby. Upon inspecting it, the young boy was astonished to realize that the black of the blackbird was not actually black—it was a rainbow of iridescent hues.

Suddenly the bird gave out a call, and as it did, the bright red-orange patch on its wing flashed intensely in the sunlight. Overwhelmed by his unexpected discovery, Haworth ran home to try to re-create with crayons the colors he’d just seen. That didn’t work out very well, due to the limitations of crayons. But looking back, the 65-year-old award-winning landscape painter has never forgotten the experience of finding a spectrum of color where he expected nothing but black. “It was such a revelation,” he says. And it’s telling that this revelation took place outdoors: Spending time in nature, in boyhood and to this day, has been an enduring, underlying source of his passion for creating art.

Haworth (pronounced hah-worth) had other memorable early experiences that stirred his interest in the world of art—although, for a time, a competing obsession with music came close to winning out.

- Mark Haworth, A Chill in the Air, oil, 30 x 40.

- Mark Haworth, Contrabando Spring, oil, 30 x 40.

- Mark Haworth, Desert Rain, oil, 28 x 24.

His father worked in advertising and sometimes took his son to visit the studios of commercial artist friends, where drafting tables and graphite pencils under big fluorescent lights left a strong impression. Even stronger was the spell under which the young Haworth fell every time he encountered the work of such artists as 19th-century American landscape painter George Inness. In each museum to which his parents took their six kids on cultural outings, Mark would immediately ask the docents where to find Inness’ art.

On the other side of the family’s creative coin, Haworth’s mother was a concert pianist, and many of the artist’s early memories include a soundtrack of classical music from her hands on the keys. He regrets now that he declined piano lessons in favor of time spent playing outside. But one of his older brothers had a guitar, which he stealthily tried out, since it was supposed to be off-limits. Then when Mark was 11, the Beatles burst onto the American music scene. “I thought, my gosh! You can grow your hair out, get a guitar, and play, and girls will chase you!” he says, grinning.

When a rock band formed by junior-high friends lacked a bass player, Haworth talked his father into shelling out $250 for a bass guitar and an amp—a substantial sum in the mid-1960s—and joined the band. He learned to fingerpick, a skill that eventually led to classical guitar, which he continues to enjoy playing. When it came time for college, Haworth’s choice of Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, TX, didn’t offer courses in classical guitar. So he decided to study music fundamentals and then transfer to another school, intending to become a studio musician. But before the end of his freshman year, his plans had undergone a radical shift.

It started with a girlfriend whose father, Glenn Bahm, was a professional artist specializing in portraiture. Bahm had embarked on a project in which he printed lithographs on canvas of a portrait by 18th-century Italian artist Pompeo Batoni and then used oils to paint the image over each print. His daughters were assisting him, and Haworth asked if he could help with the painting as well. Bahm agreed, and thus began three years of working in a manner that Haworth likens to an old masters’ apprenticeship.

- Mark Haworth, Golden Ocotillo, oil, 24 x 18.

- Mark Haworth, Rising Mist, oil, 18 x 24.

- Mark Haworth, Technicolor Coat, oil, 12 x 16.

Initially the young artist simply blocked in colors, but he caught on quickly and soon was involved in more advanced aspects of the work. He learned to mix and apply paint, render a variety of textures, and train his eye to reproduce what he saw. “We worked on 20 prints at a time that first summer, so I painted every section—the man’s vest, the feather pen, the fur collar—20 times,” he says. “I realized I had natural talent. It just opened up a whole other door, and by the time my sophomore year came, I knew what I wanted to do.” He switched his major to art while continuing to work with Bahm, sometimes painting backgrounds for the older artist’s original portrait commissions. Meanwhile, he began taking on portrait commissions himself, and also turned to what became his passion—the landscape.

While still a junior in college, Haworth was invited to take part in his first gallery show. Soon after earning his degree in 1977, he met his first patron, an oilman who bought four of his landscapes and also commissioned him to create one new painting each month for two years. Living in a garage apartment in Huntsville and paying only $65 a month in rent, he was able to step directly from school into a career as a full-time fine artist. “That period helped me really develop my landscape painting,” he says. Before long he began phasing out the portrait work, happy to no longer be dealing with multiple sittings, finicky subjects, and squirming kids. “My personality in painting is to really get into the work while the inspiration is fired up, and get it done,” he says.

Haworth’s inspiration became intensely fired up when he discovered the beauty of the Texas Hill Country, with its wooded canyons, rivers, carpets of wildflowers, and limestone cliffs. He moved to Fredericksburg to live within his favored landscape and stayed there for almost 34 years. During his early years in Fredericksburg he took advantage of workshops offered by Cowboy Artists of America members, including Robert Pummill, William Moyers, and Howard Terpning, with whom he studied twice. “Their work really appealed to me—they’d been some of our country’s greatest illustrators,” he says. While he wasn’t drawn to cowboy imagery for his own work, “these artists really know the fundamentals of painting,” he points out.

Meanwhile, in the early 1980s on a road trip to return a car to his sister, Haworth found himself close to Big Bend National Park and thought, why not? He took a turn, entered the park, and ended up staying for two weeks. Since then, the ruggedly magnificent terrain has “become my destination,” he says. It also provided an introduction to his future fiancée. In 2012 Haworth was in a show at InSight Gallery in Fredericksburg, where a woman named Victoria purchased one of his Big Bend paintings. He learned that her family owned land near the park and that she had been going there since she was 3 years old. Her family invited Haworth to visit and paint on their land. Thus he and Victoria began communicating and visiting each other, and now the two are engaged. “She bought a painting and got the artist as a rebate,” he jokes.

- Mark Haworth, Thunder Over Boquillas, oil, 24 x 36.

- Mark Haworth, A Shady Spot, oil, 24 x 36.

- Mark Haworth, Canyon Sentinel, oil, 12 x 12.

In early 2017 the couple moved to the outskirts of Austin. Still surrounded by the Hill Country, Haworth continues to paint that landscape, while he and Victoria also regularly spend time at Big Bend. He works from oil sketches, drawings, and his own photographs and, these days, also from Victoria’s photographs. “She has a great eye for compositional design, and her black-and-white photos I find really stunning,” he says. One such collaboration resulted in GOLDEN OCOTILLO [see page 57], in which the graceful, spindly desert plant is backlit against a wall of shadowed rock. “It was a fun tapestry of shapes and textures. The desert allows you to do that,” Haworth says.

Just south of Big Bend is a setting Haworth has painted a number of times. At the foot of a towering, rose-hued escarpment, the Mexican village of Boquillas del Carmen sits beside the Rio Grande. After the border was closed for a time and then reopened, the artist returned and found that much of the village had been freshly painted in bright primary colors. On the day he was there, enormous storm clouds were building up over the mountains, yet as the clouds pushed skyward, parts of the cliff face and houses below remained bathed in sunlight. For Haworth, THUNDER OVER BOQUILLAS [see page 58] suggests the resiliency of people who have lived for centuries in a harsh desert environment, their tiny hamlet of colorful houses signaling strength despite being dwarfed by the landscape and weather.

The painting reminds Haworth of George Inness’ response to a question posed by a writer for Harper’s Magazine in 1878: What does an artist do? “The true purpose of a painter,” Inness replied, “is simply to reproduce in other minds the impression which a scene has made upon him. A painting’s real greatness consists in the quality and the force of this emotion.” Sitting in the studio in his hilltop home, with French doors open wide to the courtyard, Haworth reflects on the 19th-century painter’s words. “That’s what I try to do,” he says. “When my emotional response to a landscape hits me like that, I’m hoping to pass that feeling on.”

representation

InSight Gallery, Fredericksburg, TX; Collectors Covey, Dallas, TX; www.markhaworth.com.

- Mark Haworth, Chilled Pears, oil, 11 x 14.

- Mark Haworth, Fishing the Guadalupe, oil, 9 x 12.

- Mark Haworth, Rio Bravo Kaleidoscope, oil, 9 x 12.

This story was featured in the February 2018 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art February 2018 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook