Propelled by his grandfather’s story, Texas painter David Griffin comes home to western art

By Gussie Fauntleroy

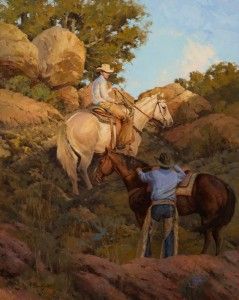

David Griffin, Eden Under a Blue Sky, oil, 30 x 24.

This story was featured in the October 2013 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art October 2013 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story!

It all started with a story that could be sad—a young boy abandoned on the north Texas plains—but that turned out just fine. In fact, for David Griffin, it turned out better than fine. If not for his grandfather’s story and nickname, both handed down through the family, the Dallas-based painter might never have connected with his true artistic path.

The story goes like this. It was the fall of 1899 or 1900, and 11-year-old L.M. Griffin had been passed around among relatives for a time after his mother died. Then, so the story goes, L.M.’s father got a notion to go to California to be in the newly invented silent pictures and left his young son behind on his own. Wearing all the clothes he owned, the boy wandered until he came upon the sprawling Matador Ranch, where the foreman took him in and gave him a job.

When spring came and the weather warmed up, the boy began shedding layers of clothes—a pair of pants, a couple of shirts. One of the other ranch hands noticed and said, “Hey look! That kid over there looks like a snake comin’ out of his skin!” So the cowpokes nicknamed him Snake. When he was a teen they called him Reptile, which later morphed into the more acceptable cowboy nickname, Rip. For 10 years in the early 1900s, until he married, Rip worked as a cowhand on the Matador Ranch. When his son was born, he was nicknamed Rip, who passed the nickname on to his son, David. The moniker then skipped a generation and landed on the artist’s grandson, the fourth Rip.

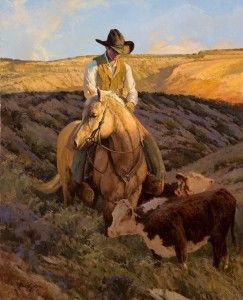

David Griffin, Weathered Moon, oil, 24 x 36.

But the family legacy involves far more than a name. It conjures the vastness of the Texas plains and the solitary, hardworking life of an early 20th-century cowhand on that stark land. The story inserted itself into Griffin’s boyhood imagination alongside 1950s cowboy icons like Roy Rogers and Gene Autry. It brought real horses into his life when his grandfather was back on the Matador, and later when he had his own small ranch and taught his grandson to ride. Then the pull of the windswept land and the values of cowboy life lay dormant in Griffin for years—until they re-emerged in his art.

Griffin’s friends have told him that as a kid in Lubbock, TX, he was always drawing, although he doesn’t remember that as a central part of his early life. “Maybe it was just something I did without thinking about it. I didn’t consciously pursue art,” the 61-year-old painter relates, relaxing in the studio at his home in an old neighborhood, where a creek and “trees as old as Dallas” provide welcome respite from the city pace.

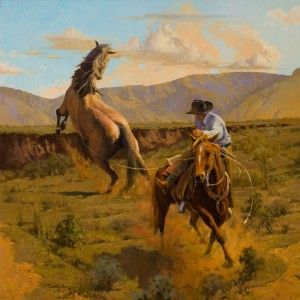

David Griffin, One Stirrup and a Big Night-Mare, oil, 36 x 36.

Griffin’s first visit to an art museum did not take place until the early 1970s at Texas Tech University, where he studied pre-med until exams and common sense convinced him he was on the wrong track. But the specter of the Vietnam draft convinced him to stay in school. So he signed up for life-drawing classes, studied under excellent instructors, and discovered he had an aptitude for art. “Nothing is a mistake,” the artist muses in his warm Texas drawl. “The spiritual aspect and my faith have been a huge part of this. It’s taught me that mistakes become part of success.” Over the years, that success has grown to include awards, participation in nationally recognized shows, and a broad collector base. And, over the years, success has been ushered in through unexpected doors.

In 1976, one of those unexpected doors took the form of an invitation to join the first-ever class of the Illustrators Workshop in New York, taught by top-notch professionals. “It’s kind of a mystery why I was invited. I was thrown into the fire with these icons of illustration,” Griffin says. “It affected me profoundly, being around those wonderful, talented people who were so much better than me, being with them and absorbing so much.” He attended the school for most of two years, working with illustrators in their studios and taking in New York City’s art museums.

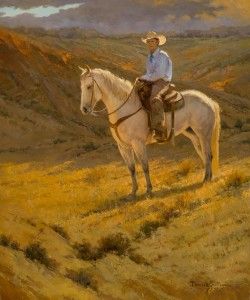

David Griffin, Last Light, oil, 30 x 24.

Returning to Texas, Griffin set up a graphic-design studio in Dallas. Two years later he happened to meet the illustrator Bart Forbes. The two became friends, and Forbes invited Griffin to rent studio space in a large house where Forbes and illustrator Jack Unruh both worked. The arrangement lasted more than 10 years. “Those were really special years,” Griffin remembers. “Bart and Jack are older, and they mentored me in a lot of areas. It was an act of kindness, another opportunity to be around world-class artists.”

After eight years of working in graphic design while painting on the side and using half his studio to show his fine art, Griffin met gallery owner Tony Altermann. Altermann and Jack Morris, who together owned a Dallas gallery at the time, represented Griffin for a number of years. They took the painter under their wings, teaching him the difference between illustration and fine art and mentoring him on the business side of fine art. “It was another example of something I wasn’t looking for that came along,” the artist marvels.

Still, Griffin’s deeper artistic calling—masterfully rendering cowboys and landscapes of the West—had not yet come along. Following the inspiration of earlier American painters drawn to the color and light of France, he was primarily painting scenes from various regions in France, where, for several years, he and his wife, Lorna, spent time each year. One day Altermann suggested he consider subject matter closer to home.

David Griffin, Passing Storm, oil, 24 x 20.

Griffin took that advice, and in doing so, he reconnected powerfully with his earliest roots. He began to understand the struggles and satisfactions of his grandfather’s genuine cowboy life. Beyond the romanticized imaginings of a Texas-bred boy, he discovered nuances, emotions, and narratives that could be conveyed through paint. And gradually he learned to appreciate and visually express the harsh beauty that permeates both the western landscape and the life of those who make it their home by working the range.

“Comparing the beauty of the south of France with the beauty of a Texas sandstorm and the gritty stories of West Texas—I had to discover what that kind of beauty was,” he explains. “Then I began to understand the legacy and heritage of where I was raised, and the visual value of that. It was nice to come back home, to sink roots and push the art to another level. To be honest, the painting got a little easier to work through. Not that it’s ever easy, but I had a deeper well, a deeper source of resources and inspiration that I hadn’t known I had.”

Griffin’s aesthetic appreciation for terrain that many consider desolate is reflected in much of his work. EDEN UNDER A BLUE SKY, for example, suggests the deeply personal nature of one’s idea of paradise. As the painting’s title suggests, for these two mounted cowhands—one in shadow and one in sunlight—there is probably nowhere else they would rather be. Likewise, the viewer is offered a visual sense of their pleasure through the artist’s treatment of the scene, from its rich colors and fluid composition to the comfortable, easy stance of horses and men.

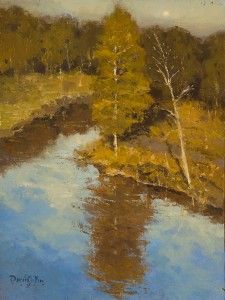

David Griffin, Back Country, oil, 12 x 9.

Weather is a constant and unpredictable companion on the range, and in PASSING STORM a young cowboy appears to consider his options as dark clouds build. Yet he and his horse are still in the sun, which glows through the brim of his hat. “The light through his hat almost appears like a halo,” Griffin points out. “It says something about how I feel about that image—there’s a reverence about that whole thing.” He adds that the effect was not planned. “I never visually see in my head what a painting will look like when it’s finished. I start with a small idea and let it go with serendipity and figuring out how to make it work.”

A painting that required a bit more forethought was ONE STIRRUP AND A BIG NIGHT-MARE. It captures the instant when a mounted cowpoke realizes he has lost his balance while roped to a huge bucking horse. The tension is electric—it’s the split second before the rope gets taut and chaos explodes. But, Griffin observes, “Those moments of action are surrounded by many more moments of quiet.” In fact, what resonates perhaps most deeply with the artist is the tranquil solitude of life on the range. Despite its hardships and sacrifice, the cowboy’s life contains a pared-down grace that parallels the rough beauty of the land, he believes.

“I never got to give my grandfather credit for this, but if he was around, I would say thanks for doing what he did,” Griffin says. “He didn’t know the profound effect he’d have on me. There was a lot of value in that life, a lot of wonderful opportunity to learn about yourself, about nature—the sun and rain and all the elements you’re exposed to. It weathered you, but you became part of the land.”

representation

Worrell Gallery, Santa Fe, NM; Davis & Blevins Gallery, Saint Jo, TX; Lee Small Fine Art Gallery, Fort Worth, TX; davidgriffinstudio.com.

Featured in the October 2013 issue of Southwest Art magazine–click below to purchase:

Southwest Art October 2013 print issue or digital download

Or subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss a story!

- David Griffin, Back Country, oil, 12 x 9.

- David Griffin, Brother’s Keeper, oil, 24 x 20.

- David Griffin, Brothers of the Land, oil, 30 x 24.

- David Griffin, Eden Under a Blue Sky, oil, 30 x 24.

- David Griffin, Fire and Ice, oil, 30 x 40.

- David Griffin, Guardian, oil, 24 x 20.

- David Griffin, Jackson Skyline, oil, 9 x 12.

- David Griffin, Last Light, oil, 30 x 24.

- David Griffin, Life as Big as the Sky, oil, 40 x 30.

- David Griffin, Old School Teamwork, oil, 30 x 24.

- David Griffin, One Stirrup and a Big Night-Mare, oil, 36 x 36.

- David Griffin, Passing Storm, oil, 24 x 20.

- David Griffin, Weathered Moon, oil, 24 x 36.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook