Lisa Danielle’s paintings tell stories of earlier peoples and times

By Gussie Fauntleroy

This story was featured in the December 2018 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art December 2018 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

Lisa Danielle likes to think of herself as a “commission” artist, except that neither she nor the purchaser is aware of that ahead of time. “Until someone buys a piece, I don’t know who ‘commissioned’ it,” Danielle says. “Then someone says, ‘Oh my, it’s like you painted this for me!’ And I look at that person in amazement and realize why I made it.” The award-winning, Sedona-based painter has long appreciated the connection that happens when a collector or viewer falls in love with her work. But lately she has begun to think of her job as unknowingly custom-designing each piece for its eventual owner, creating an even more intimate connection.

A good example is a painting that featured artifacts related to 19th-century Plains Indian women and horses. One night Danielle awoke with a fully formed vision of the painting, complete with title. When it sold last year to an appreciative woman rancher, the artist knew it found its intended home. A newer piece, HORSEPOWER, is a masculine version of the same concept, honoring the Plains warrior’s sacred and personal relationship with the horse. The painting incorporates a Cheyenne River Sioux pipe bag and a carved dance stick, and in the background are colorful images of horses reminiscent of drawings on a teepee wall.

As she does with all her paintings, Danielle wrote a brief explanation of the historical and cultural significance of the objects in HORSEPOWER and attached it to the back of the piece. It’s an extra gift to the artwork’s eventual owner and another way of paying respect to the people who created the original artifacts. Especially when the objects are centuries old—their stories and the lives of their makers shrouded by the passage of time—the artist says, “I want to bring these things forward and into the light.”

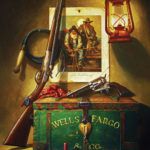

- Lisa Danielle, Along the Oregon Trail No. 3, acrylic, 40 x 30.

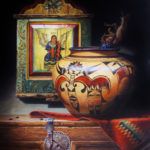

- Lisa Danielle, Circles of Influence, acrylic, 36 x 36.

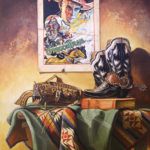

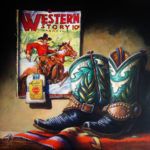

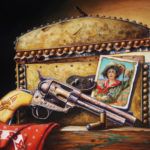

- Lisa Danielle, Cowgirl Up!, acrylic, 36 x 30.

Danielle has been drawn to things reflecting the patina of time since she began painting seriously as a teenager. Using watercolors, she thought of her interest then as “rustic Americana.” But it wasn’t easy finding examples of the subjects she liked. Old barns were rare in Long Beach, CA, where she grew up, and evidence of the region’s indigenous populations was even harder to find. One thing that surrounded her daily, though, was evidence of the astonishing power of art.

Danielle’s parents were both extraordinarily creative, eventually working together to produce bronze sculptures including animals and bonsai trees. Yet long before that, they made virtually everything for the family’s home: unusual furniture, picture frames, mosaic tables, wall decorations. “From the outside, our house looked like every other tract house, but inside, it was—different,” Danielle says. She was especially enchanted by the scene of Cinderella and a team of eight horses her mother painted on her bedroom walls. “My room was like a magical kingdom,” she says. “I could see how art could transform a space.”

Danielle’s own excursions into art began when she asked her mother for a pencil at around age 3. Knowing she had been born in La Jolla, CA, she used her imagination to draw a picture of the sea. Soon she moved on to crayons, tempera paints, and then small canvases on which she used oil paints that had belonged to her mother as a child. “Every night after my homework, my treat was to paint in my bedroom,” she says. Among other things, she copied covers of Arizona Highways magazine, always with a touch of flair. “It’s the same when I cook,” she says, smiling. “I always add a little extra spice.”

In high school Danielle took as many art classes as she could. When she was 16 she spent an afternoon in the studio of a watercolor artist her mother had met at an art show. He explained about paint, paper, and technique. “He launched my professional career. I wouldn’t be who I am if that hadn’t happened,” she says. Soon her mother was helping find buyers for her paintings among family and friends. Although teenage Lisa was also heavily involved in advanced academics, she began to think of herself as an artist. Then she enrolled in art school. “That’s when I realized I had no idea what I was doing,” she laughs.

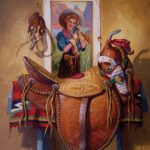

- Lisa Danielle, Feathers and Clouds, acrylic, 36 x 36.

- Lisa Danielle, Honor and Celebration, acrylic, 40 x 30.

- Lisa Danielle, Rangeland Rhapsody, acrylic, 30 x 30.

At California State College in Long Beach, she took basic drawing and painting classes and became aware that her knowledge had major gaps. Meanwhile, the art world at the time favored Andy Warhol and pop art, and fellow students were entertaining themselves by streaking across campus. She felt discouraged and out of place. “I had early success with art in high school, so I thought you just get discovered and off you go,” she says. “I didn’t know how the art world worked.”

After meeting and marrying a painter, Danielle returned to school, this time at the Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles. Her work had always been representational, but her choice of still-life subjects came into clear focus after her step-grandmother told her she had some things to show her. The older woman pulled out beautifully preserved baskets, pottery, and other exquisitely handcrafted Native American items. They had belonged to Danielle’s great-grandmother, who received them as gifts while teaching on the San Carlos Apache Reservation in southern Arizona at the turn of the 20th century. Danielle gazed at them, amazed. “Why don’t you take them and paint them?” her step-grandmother said.

With her instant, small collection in hand, Danielle began seeking out other Native artifacts, taking photos in museums and private collections and acquiring pieces when she could. In 1981 she and her then-husband moved to Sedona, and the world of western and Native American culture and history opened up to her. “There were the Hopi and Navajo reservations, the southern Arizona Indians, the pre-history of the Four Corners area, and big ranches all around. It was like being dropped into a living-history museum,” she says.

- Lisa Danielle, The Evening Stage, acrylic, 40 x 30.

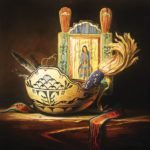

- Lisa Danielle, Angels of the Pueblos, acrylic, 24 x 20.

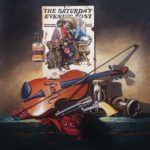

- Lisa Danielle, Cowpuncher Pastimes, acrylic, 18 x 18.

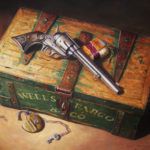

Today Danielle’s paintings feature Native American artifacts or assemblages of items from the cowboy world, the latter tending to a romanticized view. RANGELAND RHAPSODY was inspired by a Norman Rockwell painting on the cover of a 1927 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. The wistful, mustachioed cowboy in the image, she says, looks just like a ranch foreman she met at a chuckwagon on the Double O Ranch. She reproduced the magazine cover along with a pistol and a violin, in homage to the lonely cowboy who would play his fiddle to keep himself company while watching the herd at night. Later, a painting of the foreman’s wife’s well-worn boots became a best-selling Leanin’ Tree greeting card.

“I grew up with cowboy and Indian westerns, and that started something deep that surfaced later,” Danielle says of her love of the Old West. For a time, living outside of Sedona, she had horses. Now she lives closer to town and rides a vintage Honda 450 motorcycle she named Hi Ho Silver. “It’s my iron horse with a studded saddle. It makes me happy,” she says.

Standing at one of two easels in her converted garage studio also makes her happy. After years of working in watercolor, Danielle switched to oil and then, about 15 years ago, transitioned to acrylics. The medium is a good fit for someone who gets excited about what she’s doing and doesn’t want to wait for paint to dry. Rich undertones and multiple glazes can be applied one after another, adding to the depth of color and the drama of lights and darks. The artist’s aim is to catch the eye from across the room and then treat the viewer to finely rendered details up close.

- Lisa Danielle, Guarding the Gold, acrylic, 18 x 24.

- Lisa Danielle, Storm Patterns, acrylic, 40 x 40.

- Lisa Danielle, Cowgirl Spirit, acrylic, 12 x 16.

Recently Danielle has begun working bigger, sometimes depicting objects larger than life size. And her compositions, especially those featuring Native American artifacts such as pottery, have become more clean and spare. “I’m a storyteller, but a lot of objects can tell their own story, so I make it bold and simple to achieve that peaceful sense of existing alone,” she says.

In fact, she will always remember the words of the wife of a Montana physician who collected her art. “Cancer medicine is very stressful,” Danielle says, “and the doctor’s wife told me: ‘When he comes home at night, sometimes he goes to the front room and turns on the light over every painting of yours, and stays as long as it takes to calm down and be human again.’”

For Danielle, this kind of response to her art makes sense, since many of the objects her paintings depict were created not only for utilitarian purposes but also for beauty. They express what she believes is a universal aesthetic that continues to resonate across cultures and time. “I want to create a sense of serenity based on a long tradition of people who knew how to face adversity with serenity,” she says. “Most of the stories my work tells are just about our human existence and what generations continue to find useful and beautiful.”

representation

Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, AZ; Mockingbird Gallery, Bend, OR; Sorrel Sky Gallery, Santa Fe, NM, and Durango, CO; Mountain Trails Gallery, Sedona, AZ, Jackson, WY, and Park City, UT; Mainview Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ; www.paintbrushranch.com.

This story was featured in the December 2018 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art December 2018 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook