David Caton’s paintings evoke the landscape’s transcendent power

By Gussie Fauntleroy

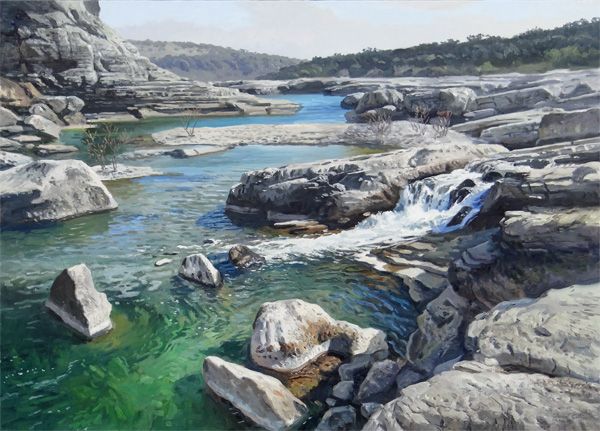

David Caton, Pedernales Falls, oil, 36 x 48.

This story was featured in the June 2018 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art June 2018 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

If you didn’t know that David Caton was a landscape painter, the first sign you might see of his lifelong, deep connection with nature—assuming you bypass the painting studio that takes up the entire downstairs of his Texas Hill Country home—are the glass cases that hold his extensive collection of seashells from around the world. The second sign is revealed in his prints of ancient Japanese and Chinese landscape paintings, images that gracefully suggest the power of nature to open the human spirit to a transcendent realm.

These two collections point to distinct but compatible aspects of Caton’s character that emerge, in turn, on his canvases: the close observational eye of a naturalist and the sensibility that perceives more than what’s there in front of his eyes. The paintings that result are simultaneously rooted in actual locations, with recognizable and skillfully rendered landmarks, and enhanced through light and composition to elicit deeper qualities of the human connection with landscape.

- David Caton, Boquillas Canyon, Downstream, Big Bend, oil, 48 x 48.

- David Caton, Chisos From the West, Big Bend, oil, 36 x 48.

- David Caton, Frio at Garner #6, oil, 36 x 60.

On location, Caton produces small paintings in oil that serve as reference for his studio efforts but are also finished pieces in themselves. In the studio, he often works in an intermediate size, creating one or more 30-inch paintings based on the smaller composition. Through these, he hones his conception of a final piece, which may be as large as 60 by 48 inches. He likes to think of a certain paradox that can happen in art: A small painting may conjure a sense of monumentality, and a large-scale work can contain elements that feel intimate. The 62-year-old artist aspires to both.

HOT SPRINGS canyon #5 is a good example. It depicts a soaring view of the Rio Grande from a vantage point high on a canyon rim in Big Bend National Park. The location is among Caton’s recent choice painting spots within the park, which is one of his all-time favorite destinations. In this piece, both the canvas size and the vista itself are large in scale. Yet within the image, which he produced with relatively small brushes, the space is broken up through shapes, shadow, and light, creating approachable, intimate places for the eye to land and linger.

The immensity of the landforms at Big Bend and elsewhere in the West was not something Caton lived with as a boy. Born in Pasadena, CA, he grew up in St. Petersburg, FL, and Houston, and each summer he and his younger brother and their parents piled into the car to visit relatives in California. “I loved St. Petersburg, but it was so exciting to drive west and start seeing the mountains,” he remembers. These visits were important for another reason as well. Caton’s grandmother, Myrtle Caton, was an artist, a “fine portrait painter,” he says. While she didn’t teach him directly, he spent long stretches of time watching her paint. When David was 16, Myrtle encouraged his parents to enroll him in private painting classes. As it turned out, the instructor he found became an influential mentor, plein-air painting companion, and decades-long friend.

- David Caton, Hot Springs Canyon #5, Big Bend, oil, 60 x 48.

- David Caton, Pulliam Bluff, Big Bend, oil, 36 x 48.

- David Caton, Rough Run Creek, Big Bend, oil, 48 x 60.

When teenage David put together a portfolio and first showed up in the Houston studio of landscape painter Bill Zaner, the older artist flatly announced that he didn’t teach children. “I was a pretty shy boy, but I was persistent,” Caton recalls. His talent and enthusiasm were persuasive, and so every Thursday night through his high-school years, he and a few other painting students worked with Zaner. They often traveled together to Big Bend or to Padre Island National Seashore to paint on location. Although Caton had been handling paint since he was a young boy, Zaner dramatically raised the bar. “Bill was a master of going into the studio and composing a better painting from sketches he’d done in the field,” he says. “He would inject a bit of imagination. In the studio a painting gained a theatrical aspect, whereas plein-air work was the perceptual part.”

At the University of Houston, where Caton earned a bachelor’s degree in fine art, his awareness of the diversity of approaches to painting grew exponentially, especially through the instruction of painter Richard Stout. Stout offered his students perspective-expanding assignments, including reading lists on the literary aspects of art. He introduced Caton to such transcendental landscape painters as Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840). Stout was also instrumental in securing travel grants that took Caton to Germany and elsewhere in Europe, where the young painter was exposed to centuries’ worth of art history. He was particularly inspired by the work of Swiss-German symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901).

Back in this country, Caton earned a master’s in fine art from Yale University, and for 10 years he produced and exhibited enormous imaginary landscapes—as large as 9 feet—featuring mythological figures and symbolist themes that referenced Böcklin and touched on the sublime. Then, in 1989, his attention was drawn back to the actual land-scape in the here and now. A friend from graduate school bought a ranch in southern Arizona, and Caton accepted an invitation to visit, taking along his paints. Afterward he spent a month on the road, painting in national parks around the West. “As soon as I started painting outside, I fell in love with it all over again,” he says.

- David Caton, South Rim, Grand Canyon, oil, 60 x 48.

- David Caton, Boquillas Canyon, Afternoon, Big Bend, oil, 48 x 54.

- David Caton, Dead Horse Point, oil, 36 x 48.

In the 1990s Caton reconnected with Zaner, and the two began painting together again. They made many painting trips, often to Big Bend, before his former mentor’s death a few years ago at age 85. When he first returned to plein-air painting, Caton was drawn to the spectacular, iconic landmarks of the West. He still enjoys magnificent locations like the Grand Canyon and has painted at Big Bend well over a hundred times over the years. But after moving to the small Hill Country town of Utopia, TX, almost two decades ago, he found himself turning more of his attention to the wealth of compelling subjects just a few miles from his door. In particular, he discovered a fascination with painting water.

It started after he attended a show at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, where he saw a John Singer Sargent painting of a small brook. Wanting to develop a looser approach in some elements of his work, Caton immediately grasped the artistic opportunity provided by water. “Here’s a subject that offers the possibility of getting very abstract with the composition. What’s on top of water, what’s underwater—it can become very abstract,” he says. As it happens, Caton lives close to some of the clearest, most inviting water imaginable: The Hill Country’s many rivers flow over and through pale limestone boulders and cliffs, enhancing the water’s sparkling beauty.

Caton painted FRIO AT GARNER #6 at one of his favorite spots along the Rio Frio in Garner State Park, just a few miles from his home. In summer the park is crowded with visitors, but in winter he can walk along the river all afternoon and not see another soul, just the continual movement of crystal-clear water and perhaps a deer wading in the shallows. As with all his work, Caton began with small paintings of the actual scene and later, in the studio, drew on years of experience and a touch of imagination to improve the composition. In this case he arranged rocks, shadows, and the flow of water to suggest a subtle “X” formation in the center of the painting, with the water taking on a different character in each section of the piece.

- David Caton, Frio at Garner, Late Afternoon, oil, 42 x 72.

- David Caton, Hot Sp. Canyon #2, Big Bend, oil, 54 x 48.

- David Caton, Hot Springs Canyon #6, Big Bend, oil, 48 x 54.

Combining actual perception with enhanced elements is a way of seeing beneath a landscape’s surface to the underlying feeling it can convey, Caton says. “When I’m out there, I’m looking at shapes and negative spaces. I see a landscape that speaks to me on a gut level, and I get very excited when I see a composition—maybe a big, upside-down yellow triangle, then maybe a little circle over there. I think all those formal aspects of a painting can really reinforce the feeling of the subject.”

That feeling can be powerful. As a self-described transcendentalist when he’s immersed in nature, Caton appreciates the potential of the landscape—and certain landscape paintings—to move us beyond the literal and into an experience of quiet wonderment and awe. “The 19th-century notion of the sublime may be an antiquated way of thinking about nature,” he says. “But I’m amazed, looking back at Japanese and Chinese paintings—they had notions thousands of years ago that were popular in the 19th century.”

Intertwined with this is a desire Caton believes many people have to return to the pure joy of a child’s experience of nature. He’s thinking of the 19th-century English art critic John Ruskin, who wrote of how a child’s view of beauty is so often replaced by a scientific perspective in adults. For Caton, the goal with his own experience of nature, and in his art, is to move beyond this second stage to a place where nature is perceived “with all the knowledge of the 21st century and also with what I believe to be real,” he says. “We know we can never be at that first level again, but in some ways we get to where the beauty is more real and free of sentimentality. It’s more true.”

representation

William Reaves | Sarah Foltz Fine Art, Houston, TX; Texas Treasures Fine Art Gallery, Boerne, TX; Hunt Gallery, San Antonio, TX; www.davidcaton.com.

- David Caton, Hot Springs Canyon Morning #3, Big Bend, oil, 48 x 48.

- David Caton, Mule Ears, Big Bend, oil, 36 x 48.

- David Caton, Mule Ears, Morning, Big Bend, oil, 36 x 48.

- David Caton, Nueces, Looking Downstream, oil, 36 x 48.

- David Caton, The Sawtooths, oil, 48 x 60.

- David Caton, The West Side of the Window, Big Bend, 48 x 48.

This story was featured in the June 2018 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art June 2018 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook