By Gussie Fauntleroy

An enormous black bear lowers his head and leans on one massive paw as he feeds on tender, early summer sweetgrass in Yellowstone National Park. Forty yards away in the protection of a Chevy van, Bart Walter’s hands and eyes are swiftly working—bending aluminum wire to the shape of the bruin’s massive curved haunches and extended front leg. The artist’s eyes continually move between the animal in the meadow and the likeness taking form around a supporting rod on a plywood stand.

When the wire sufficiently expresses the stance and sheer physicality of the bear—on a small scale—Walter fills in the form with crumpled pieces of the national park’s regulations brochure, having this once forgotten to bring along the usual aluminum foil onto which he later applies a surface of wax.

With his gaze alternately absorbing the bear’s slow movements and the swift, careful work of his own hands, the sculptor reaches for flakes of wax that have been warming on the dashboard in the sun. He presses and spreads the softened material in broad, quick strokes, leaving the surface marked by his thumbs and by irregular spaces between small slabs of wax.

He adds the suggestion of eyes and thick muzzle; he smoothes the curve of hindquarters, adjusts the bend of a leg. With each motion and subtle change, the likeness is refined. Anything that does not convey powerful male bear quietly feeding on grass is pulled or pressed into a truer shape, finally reflecting the essence of the magnificent wild creature doing what a bear in its natural habitat does.

Walter, whose award-winning, internationally collected art has been featured in a number of solo museum exhibitions, is among very few wildlife sculptors who work—from start to finish, in the case of a small piece—from life. Rather than rely on photographs, memory, or sketches (although he does occasionally refer to these), the Maryland-based artist spends long stretches of time in the presence of the animals he is drawn to, sculpting them en plein air. The results, charged with the excitement and energy of direct experience and spontaneous response, are a far cry from the “excruciatingly detailed” style of wood carving for which he once was renowned.

The magnetically powerful attraction that pulls Walter outdoors into the wilds of western mountains, African savannahs, and even the hardwood forests of his own gently rolling twenty acres near Westminster, MD, had its origins not far from his present home. Growing up in Baltimore, young Bart spent summers at the family’s cottage near the Chesapeake Bay on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. With his black Lab retriever trotting and sniffing nearby, he spent hours wandering in the marshes and piney woods. It was an area rich in wildlife, especially birds. “I spent a great deal of time on my own,” he relates. “I’d climb in a canoe or put on hip waders and just explore.”

Now 53, Walter still enjoys traveling off the beaten track. Indeed, he is a fellow in good standing at the international Explorers’ Club. “That aspect of life is a large part of who I am,” he reflects, “not in the sense of [the explorer David] Livingstone, going where no white man has set foot before. Just a personal exploration of things that are new to me.” That spirit has taken him to geographically distant, untrammeled places. It also has led to creative realms that have challenged his concepts of what he believed he could do.

Through it all has been not only a fascination with wildlife, beginning with Maryland’s deer and birds, but also with art. As a boy Walter made frequent visits to Baltimore’s art museums, standing at length before such sculptures as Rodin’s THE THINKER and works by 19th-century French sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye. “Those impressed me deeply. Rodin’s sculpture was very powerful—the forms, the weight of it—and I was drawn to the action and fidelity to nature that Barye captured in bronze,” he recalls. Among painters, the French Impressionists, with their evocative suggestion of place, claimed a strong hold on his creative imagination.

At age eight Walter took up a penknife and began carving birds in wood. By the time he was 14 he was creating ducks from old two-by-four boards, still using a penknife, although he soon stepped up to basswood and better tools. As a student at Hiram College in Ohio he earned spending money with his bird carvings, and after graduating with a biology degree—his father insisted he study something more “serious” than art—he turned his passion into a profession. By the mid-1980s Walter had become known as one of the world’s top wildlife carvers, producing works in which every delicate feather was exquisitely carved.

Yet this minutely detailed level of realism eventually came to feel like an obstacle to the emergence of an even greater creative movement. “Carving in wood was frustrating because I only got one shot at the form,” the artist observes. “I was feeling tentative and not happy with that, especially with those last few millimeters of wood. It didn’t seem to be driving at the core of what I felt sculpture was about.”

Having used clay to shape preparatory models for the birds he carved in wood, he found himself contemplating a shift in medium. “I realized the clay models had far more life, far more motion and gesture than the finished works in wood. I think my roots were calling to me—the sculptures I saw in museums as a boy. When I started switching to clay I realized I did not want it to be about surface texture; I wanted it to be about the essence of the animal.” Training himself in this new way of working, the sculptor read countless books, including several biographies of Rodin, studied the work of Rembrandt Bugatti—whose sculpture was enormously influential in Walter’s development—and spent days on end in art museums. Then, in 1986, Jane Goodall stepped into his life and presented him with a challenge that cemented his newfound artistic path.

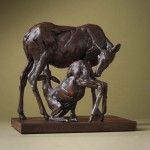

Walter’s wife, Lynn, was earning a master’s degree in biology at the College of William & Mary in Virginia when Goodall gave a lecture at the school. Lynn happened to be wearing one of her husband’s delicately carved feather pins, which Goodall noticed. The famed chimpanzee researcher asked Walter to sculpt a chimp for her. The seemingly simple request took two years to complete, including exhaustive research, countless visits to zoos to do sketches and clay studies, and much agonizing about producing a suitable chimpanzee sculpture for the world’s foremost chimp expert. Finally Walter created two small chimps—among his first-ever works in bronze. Goodall was pleased with them and purchased both.

Since then the artist has further developed the distinctive loose surface style that characterizes his current sculpture, which ranges in size from tabletop to monumental. Among his largest works is a depiction of five elk in front of the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, WY. The grouping, on a faux-rock outcropping, measures 50 feet long and includes a 10-foot-high bull elk.

For a decade or so Walter focused on African animals, spending months at a time in the field in Kenya, observing and sculpting everything from cheetahs to lions to giraffes. In more recent years he has turned most frequently to the fauna of North America, while occasionally making the human figure the subject of his art. Depictions of Maasai warriors reflect his deep respect for what he describes as the Maasai’s “completely staggering knowledge of the natural world.”

Walter’s own biology training comes into play as he visualizes an animal’s muscular and skeletal structure, as well as understanding its behaviors and habitat. Yet every new creature presents its own set of challenges. For example, sketching or sculpting a walking elephant requires a strategy, since even at a moderate pace an elephant covers a lot of ground, the artist points out.

“I watch, study, start an armature, and then make a big loop to get in front and let the elephant come toward us. I might do that 25 or 30 times before I’ve got what I need. I could just take a photo and be done with it,” he adds, smiling. “This way of working may just be an excuse to spend more time in the field.”

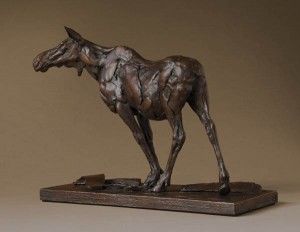

Occasionally a wildlife encounter provides more excitement than planned. While sculpting COW MOOSE—appropriately, near Moose, WY—Walter was charged by a mother moose as he tried to calm an agitated yearling by making a sound he’d heard other moose make. Fortunately, when the mamma saw he was not a moose, she relaxed and the sculptor was able, after his heart stopped pounding, to complete the piece.

Walter’s passion for expressing spot-on accuracy of gesture, movement, and balance in an animal extends as well to hands-on involvement in the bronze casting stage, where he closely oversees the finishing of each piece.

“My goal is a distillation of the subject until only true essentials are left,” he notes. “If I can reveal some intangible spirit, make evident the soul of my subject, and communicate this in my art, then I have accomplished something real.”

Representation

Gerald Peters Gallery, Santa Fe, NM; Bishop Gallery for Art & Antiques, Scottsdale, AZ; Rehs Galleries, Inc., New York, NY; Astoria Fine Art Gallery, Jackson Hole, WY.

Upcoming Shows

American Masters Show, Salmagundi Club, New York, NY, May.

Solo exhibition, African Wildlife Foundation, Washington, DC, May.

Featured artist, Western Visions, National Museum of Wildlife Art, Jackson Hole, WY, September 3-25.

Featured in April 2011.