Frank Balaam’s vibrant paintings glorify the singularity of trees and forests

By Norman Kolpas

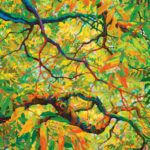

Frank Balaam, Balaam’s Wood Oak Canopy, oil, 46 x 56.

This story was featured in the July 2017 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art July 2017 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

You could say that Frank Balaam’s canvases seem ablaze with light, so brightly does a work like ENJOYING THE AIR flicker with oranges, reds, and yellows, along with the deeper greens, turquoises, purples, and blues you see at the base of a flickering flame. And you’d be metaphorically correct but also literally so, considering two key moments that shaped the artist’s life.

The first came on the afternoon of June 23, 2002. Balaam and his wife Nora were on a plein-air painting trip in the forests along the Mogollon Rim, a spectacular limestone escarpment that slashes across northeastern Arizona, when a National Forest Service Jeep pulled up alongside the couple’s RV. A ranger jumped out.

“The Rodeo and Chediski fires have merged,” he urgently told them, referring to a pair of wildfires that had begun respectively on June 18 and June 20. “Pack up and get out now!”

The Rodeo-Chediski Fire, as the conflagration was called, became the largest forest fire in Arizona history at the time. Before it was brought under control on July 7, it had burned 468,638 acres.

- Frank Balaam, Autumn Fire, oil, 44 x 42.

- Frank Balaam, Dark Red Sumacs, oil, 48 x 48.

- Frank Balaam, Enjoying the Air II, oil, 60 x 60. {

The second life-changing fire came early in the morning of July 10, 2005, when the century-old Pioneer Hotel, a four-story brick structure in downtown Globe, AZ, burned to the ground under suspicious circumstances. Balaam, who has lived in the old mining town east of Phoenix since 1986, had a studio on the top floor of that building. More than a thousand of his drawings and paintings went up in flames. “It took me two years to re-create the paintings for which I’d already received payment,” he says matter-of-factly. The impact of that loss is still present in his soft voice, which lilts with the accent of his English homeland.

Up to that point, Balaam says, he’d primarily “been painting people all my life.” Suddenly, “I identified with the trees, which couldn’t get out of the way and would live or die based on the whims of the wind. I just wanted to get back to the forest.”

Balaam’s life has always been a sort of quest for a place of primal innocence and beauty. That search began in his native Blackpool, where he was born in 1948. A working-class resort on the Irish Sea north of Liverpool, the town is best known for its 518-foot-tall Eiffel-inspired Blackpool Tower, classic amusement-park rides, and the summertime lights festival known as the Blackpool Illuminations. The Balaam home, however, seemed a world apart from these attractions. “My family was very insular,” the artist recalls. “Before I was 15, I didn’t realize all people’s houses weren’t filled with murals.” Balaam’s great-great-grandfather had painted the famed ornate ceilings of the Tower Ballroom, and his father had trained as a scene designer. “Our dining room had a huge castle over the fireplace, and a porpoise was leaping over the dining-room table. It was like living on an island looking out over the ocean.”

- Frank Balaam, Moonlight Dance I, oil, 24 x 48.

- Frank Balaam, Moonlight Dance II, oil, 24 x 48.

- Frank Balaam, A Posteval Forest, oil, 46 x 39.

When he and his classmates were asked by their teacher to draw trees, 6-year-old Frank looked out the window and faithfully rendered what he saw. “The teacher held up my drawing for everybody to see and gave me a sixpence as a prize.”

With his family’s encouragement, Balaam went on to study for two years at the Blackpool College of Art, followed by another year in Scotland at the Edinburgh College of Art. “But Edinburgh was a very formal school, with four hours of life drawing every day,” he says, explaining why he cut short his time there. “I was already technically very skilled. But I was an incredibly shy, insular character. What I needed in my life were stories to tell.”

Over the next several years, Balaam compiled stories in abundance. He headed south to London, where he sold his abstract expressionist paintings in the open air at Hyde Park Corner while living in an attic room previously occupied by Ian Anderson, leader of the folk-rock band Jethro Tull. In Paris and across Italy, he painted and sold still lifes and images of the Madonna. Then he set out to walk from Cairo, Egypt, to Salisbury, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Everywhere he journeyed, he basked in the world’s brilliant palette: the ravishing sunset tones of a Bedouin encampment on the edge of the Sahara; the deep ultramarine blues of the Pacific at dusk viewed from a freighter off the Cook Islands.

In the summer of 1968, Balaam hitchhiked across America, starting in Boston. He wound up “completely broke” in San Francisco, and made cash by selling hand-painted postcards of the city in Union Square for $1.50 apiece. Following a sojourn back in Britain and France, he returned to Boston and set up shop creating “odd pieces of furniture painted with scenes on them.” Soon his work was all the rage among top interior designers and appeared in House Beautiful magazine. Big commissions soon followed for “murals and large paintings, and a lot of trompe l’oeil,” including a commission for the penthouse of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel. “I was basically a brush for hire,” he sums up.

- Frank Balaam, Aspens at Dusk II, oil, 24 x 24.

- Frank Balaam, Awakening Night, oil, 36 x 36.

By the mid-1980s, his success came crashing down when his first marriage ended. Balaam left Massachusetts with an old bread truck he owned and a thousand dollars in cash, and he once again set off across America. That journey launched a new process of discovery, as his subject became people. Wherever his travels took him, he says, “I would meet people, go back to the truck and paint a portrait, and write a story about the person alongside it.” A year later, the truck broke down in Globe, AZ, where Balaam settled.

His style of portraiture—realistic images composed of brightly colored trails of paint in a style he describes as “linear”—gradually won the painter new acclaim. Musicians took a particular liking to him. He created well-regarded images of Carlos Santana, Boy George, and Jerry Garcia, among many others. But he didn’t gravitate to famous subjects exclusively. The state commissioned him to paint a portrait series of hundred-year-old Arizonans, and he also turned his eye to homeless people and the residents of a senior center. He also founded a company that employed up to 80 physically and mentally disabled people to make painted folk-art furniture, naming the venture Angela’s World in tribute to his late sister, who was autistic. “We’re all these strange entities interacting in life,” he says, summing up a philosophy that embraced both his artistic approach and his humanistic outlook. “It’s all color.”

Eventually, with a new girlfriend, Nora, now his wife of 15 years, Balaam was content and settled. Then came those two cataclysmic fires three years apart, followed by Balaam’s growing desire for a sublimely healing experience: “to somehow bring back to life in a canvas the feeling of sitting in life, in light, in color shining through leaves.”

- Frank Balaam, Edge of the Forest I, II, III, oil, 46 x 138.

- Frank Balaam, Gaze—Everything Turned Into a Tree, oil, 14 x 11.

- Frank Balaam, Gaze—Leaf Lightening IV, oil, 14 x 11.

Thus did he come to his current subject matter, and his very particular style of painting. “I call it ‘reverse painting,’” he says, acknowledging that the same term may be more commonly applied to a technique for painting on glass. Balaam, however, refers specifically to the fact that, instead of painting distant subjects first, then mid-ground, then foreground or primary subjects, with every layer of oil paint laid upon the previous layers, he does not overlay a single color on his canvases. Instead, he first gives the canvas a coat of the whitest gesso possible. Then, working from detailed drawings based on his travels to forests and woodlands across the country, he paints literally leaf by leaf, branch by branch. “Every brush stroke, every color, has the pure white canvas behind it,” he explains. “So the light hits the paint, then hits the white canvas, and comes back through again to the viewer with an almost stained-glass intensity.” Further intensifying that impact are brush strokes that are sometimes a quarter to a half inch thick, giving his paintings a richly sculptural quality—paintings that take as long as six months to dry completely.

But that’s no time at all, considering that Balaam’s subjects have lifespans measured more often in centuries than years. One of his favorite places provides a good example. “I was doing some Googling,” the artist explains, “and up popped a place called Balaam’s Wood.” Further research informed him that the small woodland coincidentally bearing his name, located south of Birmingham, England, “had somehow managed to survive the Industrial Revolution,” and has in recent years been restored by local citizenry. Balaam has since visited and sketched there, and paintings like BALAAM’S WOOD OAK CANOPY are the enthralling result. He donates to that namesake woodland a portion of the proceeds from the paintings he does of it, and he has also been making contributions to help support other conservancies or nature reserves he portrays.

- Frank Balaam, Gaze—Skirts of Light, oil, 14 x 11.

- Frank Balaam, Looking up to Balaam’s Wood, oil, 36 x 24.

- Frank Balaam, Marriage of Figaro, oil, 24 x 46.

Each new painting offers new opportunities for exploration. Recently, for example, he’s begun portraying night views, as in the diptych MOONLIGHT DANCE. As for more dramatic changes in direction, however, “I think you’ve really just got to wait and see,” he says.

Meanwhile, Balaam remains contentedly on his chosen path. “All my days, I sit in front of a white canvas, and I put color on it,” he says. “I’m like a little kid in a colored sandbox. How could things get any better than that?”

representation

Ventana Fine Art, Santa Fe, NM; Horizon Fine Art, Jackson, WY; The Marshall Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ.

- Frank Balaam, Rio Grande Autumn Cottonwoods, oil, 36 x 36.

- Frank Balaam, Wealth of Autumn II, oil, 26 x 32.

- Frank Balaam, Balaam’s Wood Oak Canopy, oil, 46 x 56.

This story was featured in the July 2017 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art July 2017 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

MORE RESOURCES FOR ART COLLECTORS & ENTHUSIASTS

• Subscribe to Southwest Art magazine

• Learn how to paint & how to draw with downloads, books, videos & more from North Light Shop

• Sign up for your Southwest Art email newsletter & download a FREE ebook