|

| A CUMULUS CLOUD BUILDING OVER 4TH OF JULY PEAK, OIL, 36 X60 |

By Virginia Campbell

Anyone who has visited the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City knows the dauntingly beautiful work of painter Wilson Hurley. On the walls of the museum’s Special Events Center, Hurley’s five 18-by-46-foot triptych murals, WINDOWS TO THE WEST, surround you with emotionally charged, elegantly composed visions of distinctively monumental American landscapes at sunset.

Together, NEW MEXICO SUITE, ARIZONA SUITE, CALIFORNIA SUITE, UTAH SUITE, and WYOMING SUITE speak silently—and very accurately—of the scarcely believable reality of Earth as it exists in certain near-magical locations of the western United States. In each there is a powerfully illuminated conversation between land and sky, the time-sculpted solidity versus the ethereal atmosphere. The drama plays both at a distance, where their composition holds with a sturdy, poetic architecture, and close-up, where the artist’s smallest brush stroke animates chosen detail. What kind of person could have brought off this coup of contemporary luminism, which seems too knowing and accomplished to be the work of a young artist, yet too massive in scale and detail to have been done by anyone very old?

Wilson Hurley, who painted these murals over a period of five years in the 1990s, was born in 1924. That would make him 80 years old this year. He is nearly 6 feet 6 inches tall and works out three times a week, which makes him improbably fit for the physical tasks of painting large. As to what makes the consistent freshness and ambition of his work understandable, he came late to painting and paid a heavy personal price to do so. And the quality of yearning that compelled him has staying power. The paintings being shown this June 26 at Nedra Matteucci Galleries in Santa Fe, which range in size from 8 by 12 inches to 4 by 8 feet, may well be the best expression yet of an individualistic, oddly uncompromising artist for whom age is an impressive asset.

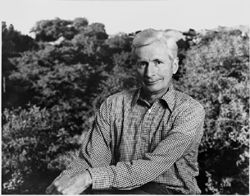

|

| WILSON HURLEY |

“I thought I was going to be Queen of the May,” says Hurley with his customary droll hyperbole as he describes the grand opening night for the murals at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. “They had an orchestra playing, and a crowd of people. When they turned the lights on and everyone looked up at the murals there was dead silence. And not a good silence. The filaments in the lights took so long to get hot enough to illuminate the colors—seven whole minutes—that by the time people could actually see the murals, nobody was looking. I was so damn mad I’d have killed the engineer. When it was over, they said, ‘Thanks, Wilson. Here’s your check,’ that’s all.”

The lighting for the murals was reworked shortly thereafter, but the experience stands as the latest ironic episode in Hurley’s self-effacing account of his life. He was born in Tulsa, OK, the son of a military man who would become a major general and the secretary of war under Hoover, and a 6-foot, brown-eyed blonde beauty who first exposed him to art when she introduced him to a well-known society painter hell-bent on doing her portrait. John Young-Hunter never did get Mrs. Hurley to sit for him, but he made a friend, assistant, and pupil of her naturally gifted son and opened up a world frequented by luminaries like John Sloan and Leon Gaspard. The young Wilson learned informally from Cézanne disciple Jozef Bakos and Theodore Van Soelen as well. But none of this was meant to prepare him for a career in art. When Pearl Harbor was attacked the year he finished high school, he went directly to West Point determined to fly in the new Army Air Corps and imagining that his life would be in the military if he survived the war.

The war had ended by the time Hurley graduated, but he served in the South Pacific, going into the jungles of Borneo to retrieve the remains of some 4,000 fliers who’d crashed during the war. “That sobered me up,” says Hurley. “It didn’t make me a pacifist, but it made me not want to become a general who sent people into war. I didn’t want a military career.” Hurley resigned his commission, went to law school, got married, joined a prestigious firm in Albuquerque, NM, had kids and led a privileged life that allowed him to be an avid Sunday painter. He practiced various kinds of law (“I defended the last man to be executed in the electric chair in New Mexico,” he says, deadpan) until the day a highly successful doctor dying slowly of cancer asked him to help with his will. Watching closely as his client sorted out priorities, Hurley went home and asked himself what he would do if he had only one more year to live. He knew the answer. “I came to the conclusion I’d get a room with north light and try to paint at least one good painting. Then I looked in the mirror at myself and said, ‘How many lives do you think you have?’”

Hurley’s father disinherited him. His wife divorced him. His colleagues concluded he was mentally disturbed. “I was frightened that after ruining my life, I’d get bored with painting,” says Hurley, but he took the damn-the-torpedoes route anyway. The painter Peter Hurd told him, “Don’t go to art school at this point. Educate yourself. I don’t know if you’ll amount to anything, but if you do, you won’t be derivative.” Supporting himself by flying for the Air National Guard, he just painted and looked at paintings. During the Vietnam War he got called up and flew in combat. “When I got home, I married my [second, and younger] wife, Roz, and had drinks thrown in my face and got called a baby killer.” But painting stayed the center of his life. His family didn’t come to his first show, because if a painting career were going to be acceptable at all, the painting couldn’t be lowly representational stuff. “My brother-in-law was on the board of the Museum of Modern Art in New York,” says Hurley. “My family thought the kind of painting I was doing put me on the level of a buggy-whip manufacturer.”

|

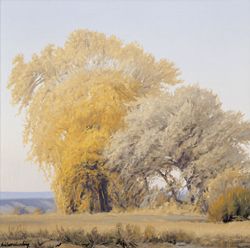

| NOVEMBER COTTONWOODS AT ALGODONES, OIL, 16 X 16. |

Modernism never had any appeal to Hurley, though. “It seems almost like anti-art to me,” he says. As for abstraction, “I don’t derive emotional pleasure from something I don’t understand.” It was landscape painting that moved Hurley, from the start. “George Inness’s PEACE AND PLENTY made light come right out of the canvas for me when I was 8 years old,” he recalls. The mentors in his process of self-education were the Hudson River painters, Thomas Cole, Frederick E. Church, et al., and the luminists who went west—Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran. “I’m not a western artist, really,” says Hurley. “I just live in the West.” It was the endlessly variable and evocative spectacle of the lit planet he lived on that moved Hurley to paint and discover it steadily anew. After some four decades, he has thought through the issues that differentiate a contemporary luminist from the 19th-century masters.

“The luminist of today,” he says, “has learned the 19th-century rules and tries to paint with their discipline, but with 100 years more understanding and knowledge about how the atmosphere intercepts color, how the laws of physics apply to the visible world, how the earth looks from viewpoints that weren’t available in the 19th century. A lot of the 19th-century luminists had strong religious conviction and were painting with a reverence and sense of mystery I’ve been robbed of. But I’ve got the intelligence to know when I hit the inside of my cranium and recognize the limits of intellect. Everything is so far beyond our capacity to be bored. I’ve been granted awareness, and I find reality and sing to it. And I want you to see it too, to pull your head out of your daily problems and look at the shadows moving under the sky.”

Hurley’s comments on his luminist forefathers are telling of his own concerns. “Inness,” he contends, “didn’t need a story,” and Hurley doesn’t either. “Church would do a waterfall, a sunset and a volcano, and I’d think, What do you do for an encore?” Thomas Moran, to whom Hurley is often compared, has indeed been important to Hurley’s development. “In his later years, he didn’t try to lie about the world so much. One time I was at the exact spot from which he painted one of his landscapes. And Moran came to me in my sleep and said, ‘You know the place across the canyon over there? You know how I put light there? Don’t do it.’ So I painted it in darkness.”

|

| FIRST DAY OF WINTER, OIL, 36 X 36. |

Part of the reason Hurley’s paintings have genuine power and lack sentimentality or nostalgia is that he understands the essential difference between a 19th-century view of, say, Monument Valley, and a contemporary one. The original luminists were painting never-before-seen, much less painted or photographed, scenes in the heyday of America’s Manifest Destiny. The glorious spectacles they painted were the blockbuster movies of their day, imbued with implied narrative about special grace. Hurley un-gilds the lily, revealing the landscapes’ inherently spectacular quality with the accurate eye he honed as a West Point engineering student and a fighter pilot. It would seem only natural if Hurley’s vision of the western landscape encompassed dismay at the harsh encroachments of population growth and industry, but he’s actually rather sanguine on that account. He sees brilliance and energy in young people he runs into—“The next generation just might save us,” he suggests—and is put off by the doom-saying of zealous environmentalists and conservationists—“Redford and that bunch.” The way Hurley sees it, “They look for things to give themselves agony.” He adds, “People who are always talking about the destruction of nature are destroying happiness for others. I can’t stand them.”

Hurley’s happiness is constantly before him, demanding a large canvas. “I was always in trouble with my galleries, doing these biggies that didn’t fit in their space. But the bigger it gets, the more enthusiastic I get. My paintings benefit from larger size up to about 8 feet. I can hold my quality at over 10 feet, but I’m not improving the painting.” For the giant canvases at the museum in Oklahoma City, he made special trips to Europe to look at murals. “I went to study the big guys, and it turns out there aren’t that many who can do the biggest images. Tiepolo is probably the best—he uses clouds to fill in most of the ceilings.” For the museum murals Hurley chose the three-part format for good reason. “The triptych lets viewers paint the area between the panels in their own minds and that satisfies their sense of beauty.”

For the last 21 years, Hurley has lived with his wife just north of Albuquerque, where he has a view of the Sandia Mountains and the Rio Grande. He works there in a 25-by-47-foot studio with a 16-foot ceiling and a 10-by-10-foot window. As always he mostly paints landscapes, though his paintings of aircraft and remembered war scenes are in the U.S. Air Force collection in Dayton, OH, and he’s done paintings for NASA, too. In the wake of painting the pieces for this summer’s show he’s been doing portraits, a genre usually confined to members of his own family. “I’d paint portraits all the time if I didn’t have to have another person in the studio with me, helping,” he says. He admires John Singer Sargent’s political skill with his subjects: “He’d get his subjects so hypnotized, he could paint a seal eating a fish and the person would look at the painting and say, ‘That looks just like me.’”

Hurley’s hypnotic skills have more to do with re-sensitizing eyes to beauty that gets camouflaged amid the hyperstimulation of so much visual media. The most special effects, his paintings argue, are the simply real ones. His sense of purpose and satisfaction—the thing he feared might desert him once he’d torn out the moorings of his previous life—has never wavered since. “Painting has never grown old,” he says. “It’s as fresh and rewarding as it was 40 years ago.”

Featured in June 2004