By Virginia Campbell

Seattle‘s Dante Marioni applies American innovation to an Italian tradition

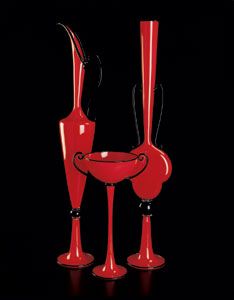

If you knew something about art, but little about contemporary glassblowing, and you saw one of Dante Marioni’s “trios”—three different vessels united by a potent color statement and a monumentally skinny approach to classical shapes—you might guess, especially given his name, that the artist behind these minimalist but show-stopping pieces was a mid-century Italian glassblower with nerves of steel and a sense of humor backing up phenomenal elegance. But then again, you’d have taken immediate note that the tallest of the pieces was an astonishing three and a half feet tall. Something about the scale of the pieces in particular would make you wonder if they could really have come into being in Venice. Still, there is a reverence for tradition in the vessel shapes, however far into the air they stretch. And there is discipline and workmanship in the degree to which they transcend the fragility of their material.

So who is behind these glass marvels? It’s very much in keeping with the confounding beauty of Marioni’s glass that he is, in fact, entirely American.

Those who know about the American studio glass movement, which began right about the time Marioni was born, know who he is. They also know who his father is, because Paul Marioni was one of the founding artists of the movement. Dante, named by his Ohio-born father after the great Italian poet, was regarded as a prodigy in blowing glass as a teenager. The younger Marioni’s success is not strictly a result of growing up around glass and following in his father’s footsteps, though. As much as he may have shown precocious finesse in a notoriously difficult field, he has also been a prodigy of a different sort—in self-direction and single-minded focus. Marioni took to glass with no overt encouragement from his father, and by the age of 18 knew so exactly what he wanted to do that, against his father’s advice, he never entertained the idea of going to art school. You can see and feel the conviction in his vessels from early on. “I didn’t need to go to art school to find myself,” he declares.

To understand how Dante Marioni’s ambition became so defined, you have to know what went on in the studio glass movement in its first two decades. The movement started with the formulation of material that could melt at lower temperatures and the invention of a small furnace that could fit in an artisan’s studio rather than a factory. This technical achievement freed glassmaking from its traditional processes and allowed a more individualistic, expressionist approach to form and color. Many artists who had worked in clay now went over to glass, and the classical shapes of glass vessels gave way to what Marioni describes, not unkindly, as “goopy, amorphous stuff.” The “loose and juicy” style often ignored function or commented humorously on it with borderline non-functional shapes, as in melting teapots. Much of the movement was hippie-inflected, and one of the prominent standard-bearers was Paul Marioni, who, armed with literature and philosophy degrees from the University of Cincinnati, moved to a hippie enclave in Marin County, CA, and gradually shifted from an auto-body repair job to glass work that was related more closely to the new expressive ethos of the 1960s than the centuries-old tradition of glass-blowing.

The most famous glass artist to emerge from the studio glass movement was Dale Chihuly, who was instrumental in starting the now legendary Pilchuck School in Seattle, WA, and is as close to a household name as any American glass artist other than Tiffany. Chihuly set glass free with his huge, luminous, nonfunctional, organic forms. Marioni, a friend, would go north from California’s Bay Area to teach at Pilchuck in the summer, and in 1979 he moved to Seattle permanently when he received a major commission for a glass window. He taught at Pilchuck and was friendly with all the people who brought fame to the school.

At age 16, Dante Marioni was working after school at a glass studio in Seattle, charging the furnaces and mixing with his father’s friends, some of the better-known artisans of a movement that now had hundreds of adherents. “I was good at drawing, painting, and photography,” recalls Marioni, “but I wasn’t a standout. My idea for a career was either playing major-league baseball or racing motor bikes.” But when Marioni began actually blowing glass, he felt an affinity for the process that sparked a curiosity and desire that far outshone those other interests.

As it happens, when Mount St. Helens blew its top in 1980, a glass artisan named Rob Adamson went to help his mother, whose farm had been covered in volcanic ash, and returned to Seattle with a garbage can of the stuff, which he then proceeded to turn into distinctive-looking black glass at the glass co-op Glass Eye. “It had an art nouveau look to it,” says Marioni, “but mostly it was a gimmick that sold really well and made the Glass Eye very successful.” This success meant the gallery needed more employees, which made it possible for Marioni to gain a full-time job there when he got out of high school. Three of his high school pals—Preston Singletary, Paul Cunningham, and Joey DeCamp—joined him at Glass Eye, and they remain best pals today.

The figure who turned Marioni’s enthusiasm into a self-directed life journey was glass artist Benjamin Moore. “I was very taken with him,” recounts Marioni. “Everyone was nice to me, but he took time. He was only 12 years older. He’d gotten an MFA at Rhode Island School of Design, he’d worked under Chihuly, and he’d worked for two years at the Venini factory, which had been the eye-opener.” Venini, on the island of Murano in Venice, was a center of supreme craftsmanship. The hippie aesthetic of American studio glass was a far cry from this glass, and Moore’s pieces, which eschewed “artistic statement” for decorative perfection, displayed a clean symmetricality that was unusual in Seattle. “I was intrigued at the transformation of a blob of goo into a technically tight thing,” says Marioni.

When Moore invited Venini glass maestro Lino Tagliapietro to teach a class at Pilchuck and…

Featured in February 2006