By Norman Kolpas

It’s late December in Southern California. There’s a brief lull in the earliest of the violent winter storms that will eventually bombard the state for almost a month. So Joan Marron-LaRue and her husband, Bob, drive from the resort community of Rancho Santa Fe, where they’re house-sitting for art-collector friends, to the beach at La Jolla, north of San Diego.

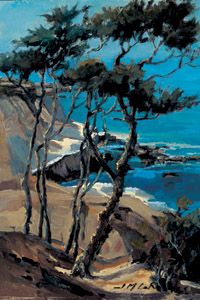

Waves 15 feet high crash into the shoreline as Marron-LaRue carries her plein-air painting gear out to the sand. She sets up her portable easel, then takes out a palm-sized drawing tablet. Holding the tablet in one hand and a pencil in the other, in little more than the blink of an eye she sketches a miniature composition of coastline and ocean no bigger than a 35-millimeter slide—“Just a quick layout and light-medium-dark value study,” she explains.

She secures to her easel a 9-by-12-inch piece of foam-core board covered with a canvas. “It has a very nice nubby texture to it, so when you move a brush across it you get a real nice drag and see-through,” she describes. She picks up a brush and, in broad blocks that aim only to capture the main masses, she re-creates her composition in light ochre.

Gradually, Marron-LaRue enters a trancelike state. Glancing repeatedly back and forth between the scene and her easel, she works her way through her arsenal of eight different brushes, laying down ever-smaller strokes and dashes of paint as her surroundings find vibrant new life on the canvas. “When that successfully happens, it’s wonderful, it’s magic,” she comments. “You don’t hear or see anything else that’s happening around you. You feel like you’re painting not just with your hand and a brush but that all your being is part of it.”

The intensity of the experience doesn’t end in the act of painting, either. “If you really tune in and you really show up for the painting,” she suggests, “then the energy of that moment will be in your canvas. And if the artist gets that energy, then the person viewing the painting gets the energy, and it’s like a three-way conference call between subject, artist, and viewer.”

The intensity of the experience doesn’t end in the act of painting, either. “If you really tune in and you really show up for the painting,” she suggests, “then the energy of that moment will be in your canvas. And if the artist gets that energy, then the person viewing the painting gets the energy, and it’s like a three-way conference call between subject, artist, and viewer.”

The whole process of making the painting takes little more than three hours—or rather, as Marron-LaRue quickly adds, “Just three hours—and 25 years.” That’s the length of time she has considered herself a serious painter, though by the standards of most folk she’s been at it for almost twice that time.

There was little obvious indication that she’d become an artist back in her childhood in Custer County, smack in the center of Oklahoma. Born in 1934, the oldest of three children, she spent most of her early years tagging along with her wheat-farmer father. “My childhood was absolutely practically oriented,” she recalls, dashing off a litany of chores and pastimes as if she drew no distinction between them: “Hunting, fishing, harvesting, gathering the eggs, playing make-believe, climbing trees, riding a horse. I rode burros and calves, too, hunted coyotes and quail with my dad, rode in a Piper Cub airplane at age 6, and swam, unknowingly, in a creek busy with water moccasins.”

As for art, “It was not something in my arena of interest,” she says. “When I started in the first grade, I did not even know how to color. I watched the child next to me to see how he utilized the crayons.”

Marron-LaRue may not have started out with instinctive artistic skills, but all that time spent outdoors sharpened her powers of observation and a sense of can-do practicality that remains strong in her to this day. “I learned that you can take anything on, even if it looks too big for you,” she says. “Go ahead and take the challenge!”

Though she became drawn to fine art in high school, pursuing such a career seemed frivolous to the practical farm girl. Her yearning took a more sensible form in fashion-arts studies at the University of Oklahoma. Following graduation and her first marriage, she taught for a while at the university and eventually worked in fashion merchandising and as a part-time fashion model.

Then her husband, an oilman, moved them to the southeastern corner of the state. “There was no fashion work to be had there,” Marron-LaRue recalls wryly. “So I started painting.”

A natural talent emerged. “I had shows, and I was represented in galleries,” she allows. But by her standards, “It was very primitive. I was very unfocused as far as direction. I was trying it all, portraits, landscapes, still lifes.”

By her late 30s, living back in Oklahoma City and looking after the two young children of her second husband, Marron-LaRue was reaching a crisis point in her dissatisfaction with her painting. “One day I said to myself, ‘You might as well face reality. You are really not going to go anywhere in the art world if you don’t go back and get the basics.’”

Thus began her serious artistic schooling. “I very carefully looked over the field of master artists and made a decision to study with a number of them for two weeks to a month at a time,” she recalls. She based each choice of mentor on what she identified to be one of her Achilles’ heels as a painter, beginning with her drawing skills. “I had never been to a life-drawing class, so I felt that was one of my major weaknesses. So I took an intense two-week master class with Hollis Williford in Loveland, CO. He taught me the value of masses, the strength of breaking subjects down into values, and how to use different types of lines—fat lines, short and round and square ones, shaggy lines, and soft-edged masses.”

Many more classes followed from teachers so numerous, she says with a laugh, “I can’t recollect all of them. I would take whatever I could absorb from one teacher, practice it, and then look for someone else who could help me.”

More and more, her studies focused on plein-air landscape work, and the list of master painters she does readily recollect reads like a roll call of top experts at painting from life in the open air: Sergei Bongart, Richard Schmid, Clyde Aspevig, Scott Christensen. A distinctive Marron-LaRue style gradually emerged, one in which she strongly acknowledges the influence of French Impressionism. “I apply a variety of colors using small strokes, in order to simulate the play of light on objects,” she explains.

Her growing self-assurance as an artist led her to travel in search of fresh, ever-more-challenging places to portray. “I respond very well to the stimuli of new subject matter,” she says. “I think wanderlust is a disorder that frequently hangs around an artist.” For weeks and months at a time, she has visited and painted in places as far-flung as France, Spain, Italy, Portugal, Russia, Nepal, Mexico, and Bolivia, and she’s planning a trip to China for later this year.

Closer to home, she’s enjoyed a more personal change of scene. Ten years ago she reconnected with and married her old high-school and college sweetheart, Bob LaRue, who had retired from his career as a school administrator. She moved with him from Oklahoma to California, and then seven years ago they resettled again in Tucson, AZ, buying a house on the eastern edge of town. They devoted a third of the spacious horseshoe-shaped residence to her career, transforming its high-ceilinged family room into a studio. They installed French doors that admit northeastern light and lined the other three walls with shelves for Marron-LaRue’s ever-growing collection of art books. An adjoining room serves as her office, and a room adjacent to that has become a gallery where she welcomes visitors by appointment.

When she isn’t traveling, Marron-LaRue can be found most mornings in the studio taking select subjects she first captured en plein air and re-envisioning them as larger canvases, generally measuring 2 by 3 feet. For such studio pieces, she’ll deliberately try to enter a meditative state. “I close my eyes and try to conjure up in my mind the feeling of what it was like being there,” she says. “It is my intent to give those paintings the same feeling of a plein-air piece, spontaneous and full of energy.”

Those same adjectives apply to the artist herself as she approaches her 71st birthday. Marron-LaRue exudes spontaneity, whether she’s recounting her childhood or attacking a canvas while stormy ocean waves crash nearby. Her energy seems unbridled as she continues to pursue a calling that—despite 25 years of study and accolades that now include membership alongside her mentors in the Plein Air Painters of America—she believes she has yet to fully master.

Those same adjectives apply to the artist herself as she approaches her 71st birthday. Marron-LaRue exudes spontaneity, whether she’s recounting her childhood or attacking a canvas while stormy ocean waves crash nearby. Her energy seems unbridled as she continues to pursue a calling that—despite 25 years of study and accolades that now include membership alongside her mentors in the Plein Air Painters of America—she believes she has yet to fully master.

“Every painting you start,” she reasons, “you’re still reaching for the carrot. There’s no sure-fire formula for how you can get a perfect painting. It’s such a challenge, and that’s why artists stay with it for their whole lives. They keep thinking the next one will be the one.”

Marron-LaRue is represented by The Max Gallery, Tucson, AZ; Monticello Fine Arts Gallery, Fort Worth, TX; Nedra Matteucci Fine Art, Santa Fe, NM; and The Howell Gallery, Oklahoma City, OK.

Featured in April 2005