By Norman Kolpas

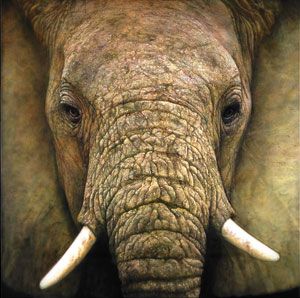

From 30 feet away or more, the eyes rivet you. They seem to follow you as you walk from one side of the gallery to another. The young male African elephant summons you with his stare, drawing you closer. He’s so huge that the 7-foot-square frame blocks his floppy ears and the top of his massive head. But his brow, tusks, and trunk appear to jut forward.

Finally, you’re standing nose-to-trunk with ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM, a recent canvas by Ray Hare. And, absorbed as you’ve been by the intense sense of reality the artist has conjured, your grasp on reality suddenly shifts. The animal’s forehead—which you’ve perceived as drawn directly from a pachyderm palette of grays, browns, and blacks—dissolves into an almost abstract composition of dots and swirls in a rainbow of colors.

For a moment, you might feel as if you’re viewing that elephant on a molecular level. Or, if you’re of a more mystical inclination, you might sense that you’ve connected with a powerful representation of the spirit that animates all creatures great and small. Then you step back a few paces, and once again, that elephant’s eyes draw you in. You’ve just experienced the sort of uncommon communion offered by Hare’s creations.

“When we think we understand something, and then something else happens to knock us off track—that’s the kind of journey on which I’d like my paintings to take you,” says Hare. On every level, from a first illusion of vividly rendered reality to a fleeting yet powerful sense that you’re glimpsing the very energy of life itself, he aims to intrigue, challenge, and satisfy the viewer.

It isn’t surprising, then, to learn that the 57-year-old California artist has achieved a measure of acclaim as big and bold as his images. He’s been exhibited in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Oakland Museum of Art, the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, and the Los Angeles Art Institute. Major corporations such as Chevron, Philip Morris, and Bank of America have Hare’s works in their collections. So do other public and private collections around the globe.

“All in all,” he says, “it’s quite a compliment to know I can sell my paintings and that’s all I have to do. In that regard, I feel very blessed and very thankful.” Blessings alone, however, can’t fully explain Hare’s remarkable success. A lifetime of training, dedication, and hard work also deserve their share of credit.

Growing up east of San Francisco Bay, Hare showed an early flair for art. And an active imagination. “I liked to daydream a lot,” he says. “It was always about escapism, getting outside or doing something other than what was going on in the classroom.” His love of the outdoors also expressed itself in a passion for sports. “Up to my sophomore year, track, football, swimming, and gymnastics were my major interests.” That all changed one day, though, when he dismounted from the gymnastic rings and landed on the base of his spine, rupturing a disc. “For about five minutes,” Hare recalls, “I was paralyzed from the waist down. Then I was in extreme pain for many months, and there was talk of surgery.”

The only cure for the pain, he discovered, was his already finely developed powers of escapism. He learned to focus his mind elsewhere: on painting watercolors. “I started painting every day, before and after school, on location and from imagination, painting outdoors and indoors and on into the dark. On a good day, I’d do as many as 10 paintings.” Not only did his body heal, but his works began to gain notice. His art teacher at Clayton Valley High in Concord encouraged him. “Mr. Enamark got me into a high school art contest sponsored by Hallmark, and I won first place in California and third in the nation. And I started getting scholarships to workshops at local art schools. That just shows you how valuable a teacher can be.”

After graduation, Hare entered the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, then went on to earn a master of fine arts degree from San Francisco State University. While all the students around him were concentrating on abstraction, he devoted himself to representational art. “There was something in me that just wanted that,” he matter-of-factly explains.

Hare also began a transition from watercolor, which he prized as an “immediate form of expression,” to an equally fluid and responsive medium, acrylic paint. That, in turn, allowed him to leap from the constraints of paper to large canvases. “All of a sudden, I had all this space. At first, it scared me. But I liked the challenge. It raised my heart level.”

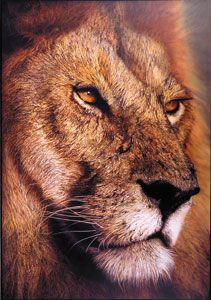

He now explored realistic images on a larger-than-life scale, in paintings measured in feet rather than inches. “What I liked was that I could enjoy a work at different distances. I liked the way an image could travel across the room, still functioning and communicating with me and asking me to come closer, then maybe taking a turn and surprising me when I arrive.”

Hare dedicated himself so wholeheartedly to larger-than-life realism that, on one class assignment in particular, he succeeded almost too well. “I actually tried to mimic in paint a half-tone photo separation. It was neurotic, I know, trying to simulate a mechanical process. All my professors thought I was trying to pass off a canvas that I’d made using photographic techniques. They almost failed me. I guess that was success,” he laughs, “in a backhanded way.”

True success, however, came relatively quickly to Hare. For more than 30 years now he’s been making his living by painting the oversized images that enthrall him, in a style he’s come to think of as “hyperrealism.” He explains, “There’s something about the term ‘realism’ that I don’t like for my approach. It implies that the painting is telling you what it’s about and what the destination is. What I like about my mode is that I want you to think the painting is very real. But then, I want the painting to give you something more.”

Hare has applied his hyperrealistic approach to a wide range of subjects, including giant fruits as well as the animal portraits for which he’s so widely heralded. Recently, he’s also begun painting large-scale human faces, as large as 5 ½ by 7 feet and tightly cropped to focus on the eyes. His aim is to create an extreme sense of intimacy, to “break down all sorts of barriers of distance and acceptance that usually have to be earned between people.”

Whatever the subject, he goes about a work’s creation in the same way. He paints five or six days a week in a large studio next to the Irvine, CA, home he shares with Susan, his wife of 33 years, with whom he’s raised three now-grown children. The space allows him to step back as far as 40 feet to get a perspective on how an image is taking shape. Blackout shades over the windows let him paint with illumination from incandescent, fluorescent, or halogen bulbs, “so I can make sure the image is working in all sorts of different lights.”

He compiles a wide range of visual sources, including photos he’s commissioned or taken himself. Once he arrives at the image that comes closest to capturing what he envisions, he uses an opaque projector to cast it on a stretched and primed canvas. “I scale it in lightly with a little pencil,” Hare explains. “Then I build up transparent layers of acrylic. I usually start with the eyes, because I love to have the painting looking back at me.”

It’s an intense process that sometimes leads to 14-hour workdays, and it takes several weeks to complete a painting. As Hare hones in on the fine details, he stands on a platform to bring him as close as possible to every corner of the canvas. “I keep tightening and tightening, going in more and more.” The process becomes so intense at times that, he says, “I feel like I’m giving blood. Then, towards the end, when the painting is doing what I wanted it to do, I go, ‘Wow! This is really why I paint!’”

His ultimate fulfillment, of course, comes when others view what he’s painted. “I want my paintings to be noticed,” he says. “But if that’s all a painting does to you, I think I’ve failed. What comes with that notice is an obligation not to be superficial, but to have a dialogue with the viewer.” And Hare takes particular satisfaction in knowing that, after more than three decades as an artist, such dialogues are happening virtually nonstop. “It’s fun to think that, at any given time of day, on any day of the year, somebody is looking at my work and enjoying it or getting something from it.”

Representation

Coda Gallery, Palm Desert, CA, Park City, UT, and New York, NY; Legacy Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ, and Jackson, WY; and William & Joseph Gallery, Santa Fe, NM.

Featured in April 2007.